Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

Are there too many of us on Earth? Part 2: Industrialocene

The ideology of economic growth and the thermo-industrial model are leading us into the wall

Flanders refinery at Mardyck on the outskirts of Dunkirk (northern France). Source: By Rádics Gergely, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51168596.

In the previous article, I highlighted a troubling coincidence between the sudden population growth of the 20th century and the sudden increase in the alteration of the earth's surface. A coincidence that naturally begs the question: after all, isn't the main problem and cause of the Anthropocene to be found in human overpopulation?

But coincidence is no proof of causality. Approaching humanity as a united block does indeed suggest a clear causality between increasing population size and worsening environmental degradation. In this article, we will see that this causality is not so obvious when we divide humanity into different populations according to lifestyle, and seek to attribute differentiated responsibilities to each of these populations in the ecological crisis.

Environmental deterioration is linked to the level of production-consumption...

It's easy to see almost perfect correlations between population size and energy consumption (which can be seen as a proxy for resource consumption), as well as between population size and CO2 emissions (which can be seen as a proxy for waste emissions).

In concrete terms, the size of the world's population has undergone an unprecedented increase between 1850 and the present day, accompanied by a sharp rise in the alteration of the Earth's surface. However, while the number of human beings has increased by a factor of 8, at the same time energy consumption has increased by a factor of over 30 [1] and gross domestic product (GDP, which can be seen as a proxy for the level of production/consumption per capita) by a factor of over 100 [2]! This means that, while there are more and more of us, each and every one of us tends to consume far more resources.

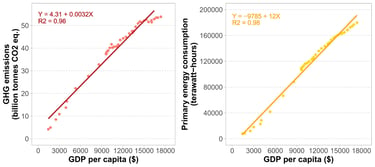

There are very strong correlations between GDP per capita (which can be seen as a proxy for individual production-consumption levels) and energy consumption or CO2 emissions.

Figure 1: Correlation between GDP per capita and primary energy consumption (left), and between GDP per capita and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (right) between 1850 and 2022. Source of data: Our World In Data for GDP per capita (https://ourworldindata.org/economic-growth) [2], energy consumption (https://ourworldindata.org/energy) [3] and GHG emissions (https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions) [4] .

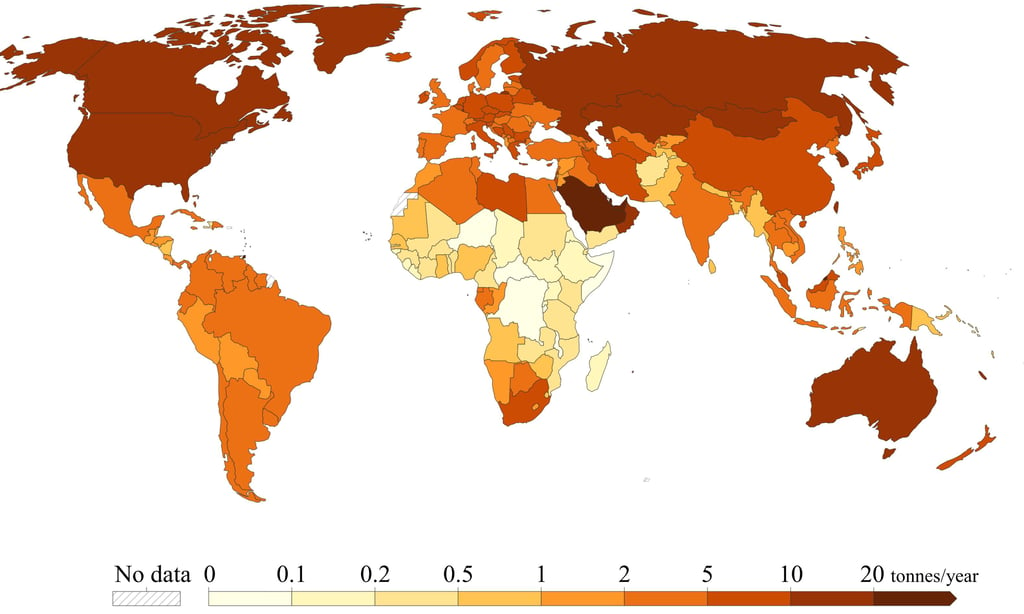

Figure 3: World map of energy consumption per capita and per country in 2023. On the whole, African countries consume much less energy than Western countries, for example. Source: Modified from Our World In Data (https://ourworldindata.org/energy) [3].

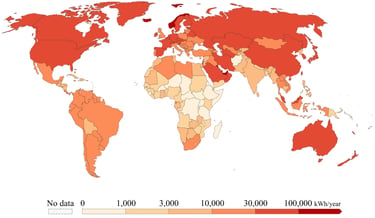

Figure 4: World map of CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry (excluding land-use change) per capita and per country in 2023. African countries as a whole emit much less CO2 than Western countries, for example. Source: Modified from Our World In Data (https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions) [4].

We can conclude from this heterogeneity that there are differentiated responsibilities in the degradation of the biosphere, and that it is unreasonable to lump together populations contributing so differently to the catastrophe.

For example, when it comes to energy, an American, Australian or Canadian consumes around twice as much as a French, Italian or Spanish, who in turn consumes on average 30 times more than an Ethiopian or Malian [3]! Mirror trends are observed for CO2 emissions [4], which is perfectly logical given the close link between energy consumption and CO2 emissions.

Clearly, the inhabitants of so-called "developing" or "poor" countries are far less responsible for the environmental catastrophe than the inhabitants of "industrialized" countries. Let's not even mention the millions of people who belong to so-called "indigenous peoples" and who have little or no responsibility.

An often-repeated example is that if everyone lived like an American, we would need five planets on Earth (a calculation based on the decried "day of overshoot"). The American way of life is non-negotiable? Above all, it is unsustainable, non-generalizable and a selfish spit in the face of the billions of people who have to suffer its consequences.

However, the level of production-consumption varies considerably even within countries. The rich clearly tend to have an environmental footprint commensurate with their wealth, as shown by their totally disproportionate contribution to environmental degradation [5]. A rich American thus has a far greater responsibility for environmental catastrophe than a poor American, but Americans on average have a far greater responsibility than Indians.

By coupling the two variables (population size and GDP per capita), the causality becomes clearer: there are more and more of us, and each of us tends, on average, to consume far more resources and emit more waste than our ancestors did; so it's only logical that environmental deterioration should increase sharply.

... which varies greatly from country to country (and within countries).

Above, we have deepened the link between population size and the level of environmental degradation by adding a "level of production-consumption" component, but continuing to treat humanity as a united block. However, a closer look quickly reveals that GDP per capita is highly heterogeneous between countries (Figure 2).

Similarly, per capita energy consumption (Figure 3) and CO2 emissions (Figure 4) vary greatly from one country to another.

Figure 2: World map of GDP per capita by country in 2023. GDP per capita is very heterogeneous between countries, but tends to be highest in Western countries (North America, Europe, Australia, South Korea, etc.) and lowest in African countries. Source: Modified from Our World In Data (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/gdp-per-capita-worldbank) [2].

A fundamental problem of vision of progress and lifestyle

Generally speaking, the way of life shared by all human beings who are followers of economic growth, which implies producing more and more, makes it impossible to reconcile high population density with preserving the planet's habitability. It's a predatory way of life, since the growth of economic activity means consuming ever more resources and emitting ever more waste.

This development model is itself underpinned by the myth of economic growth. This myth claims that the constant increase in production and consumption guarantees the well-being and happiness of the greatest number of people. This myth is put into practice through industrialization, which increases productivity and makes the consumer society possible. This industrialization is itself based on the industrial exploitation of fossil resources, as described by the term "thermo-industrial civilization".

The myth of economic growth and the associated industrial system are obviously prevalent in the capitalist system, whose primary principle is accumulation, but are also found in its best-enemy system, communism, which made increased production a central objective.

The term "Industrialocene" thus seems to me more appropriate than "Capitalocene" for describing the main cause (i.e. the growth of production-consumption through industrialization) of the recent trends characteristic of the Anthropocene, allowing us to stop burying our heads in the sand about the environmental ravages of communism, even if it doesn't solve the problem of the sometimes major impacts that predate the development of industry.

To return to the initial question, "Are there too many of us on Earth?", it's clear that it's not so much the number of humans as the lifestyle of some of them that is dragging us towards the abyss.

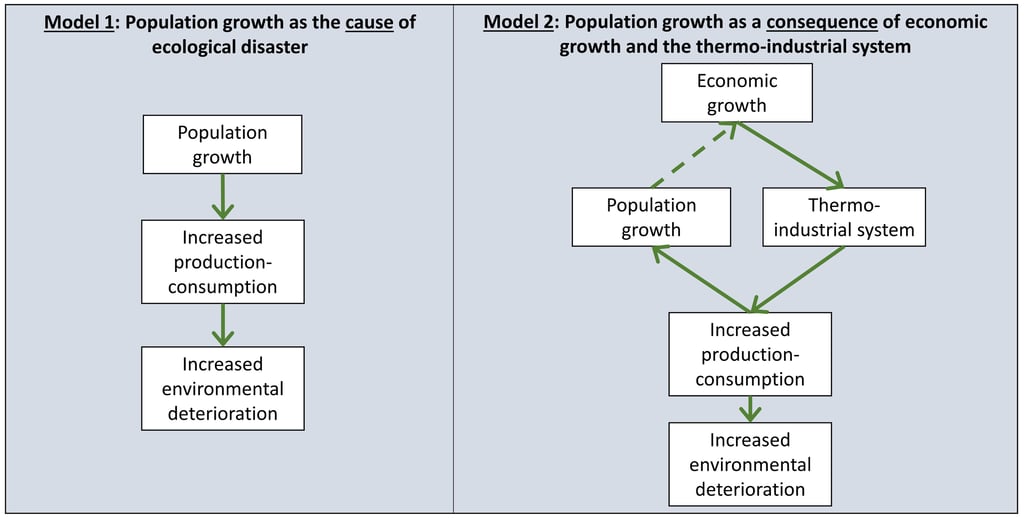

It's even tempting to reverse the initial view and see population growth not as the cause of environmental catastrophe, but as the consequence of an ideology (GDP growth as the only horizon) and the associated productivist system (Figure 5).

The ideology of economic growth and associated industrial system are spreading inexorably for a variety of reasons (an all-powerful imaginary world that aims to colonize people's consciences, brutal or more insidious initiatives to impose this model, the very real addiction of populations to the comfort that ensues, etc.). In many "developing" countries (India, China, Indonesia, Brazil, Chile, etc.), population growth is accompanied by a sharp rise in the level of production-consumption, as shown by the increase in per capita energy consumption (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Model in which population growth is the cause of increased environmental deterioration (left) vs. model in which population growth is the consequence of the ideology of economic growth and the associated productivist thermo-industrial system (right). Economic growth, which has only one golden rule (to produce and consume more and more), favours population growth both through the implementation of incentive policies and through the establishment of an industrial system that enables ever-increasing production. Population growth in turn favours economic growth through the arrival of new consumers on the market.

Figure 6: Energy use per capita between 1965 and 2023 for selected "developing" countries. These countries are characterized by both demographic growth and an increase in the level of production-consumption per person. The model combining economic growth and industrialization is catching on! Data source: Our World In Data (https://ourworldindata.org/energy) [3].

The major problem of the Anthropocene then becomes the following: more and more humans sharing the same horizon of industrial progress, made up of a continuous growth in material comfort, buildings erected as high as possible, a dense network of roads criss-crossed by powerful cars, machines to replace humans, the generalization of digital technology and ecocidal AI [6]; greedy packs whose only horizon is the accumulation of ever more consumables (goods and services, leisure and distractions of all kinds) and the preservation of their sacrosanct freedom to consume irresponsibly.

Decline in population or in the level of production-consumption?

The major problem of the Anthropocene - the part of the population taking part in thermo-industrial civilization, which produces and consumes far too much - presents two clear-cut solutions: 1) that this expensive part drastically reduces its level of production-consumption, or 2) that it vastly reduces in size (please spare me the third solution of a decoupling between growth and environmental alteration, which is a dead end).

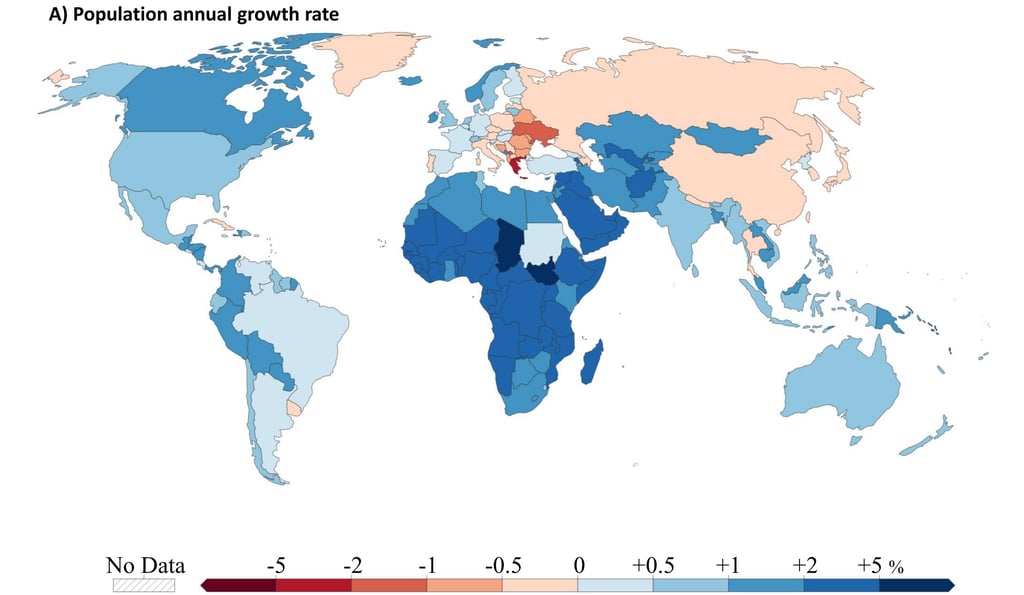

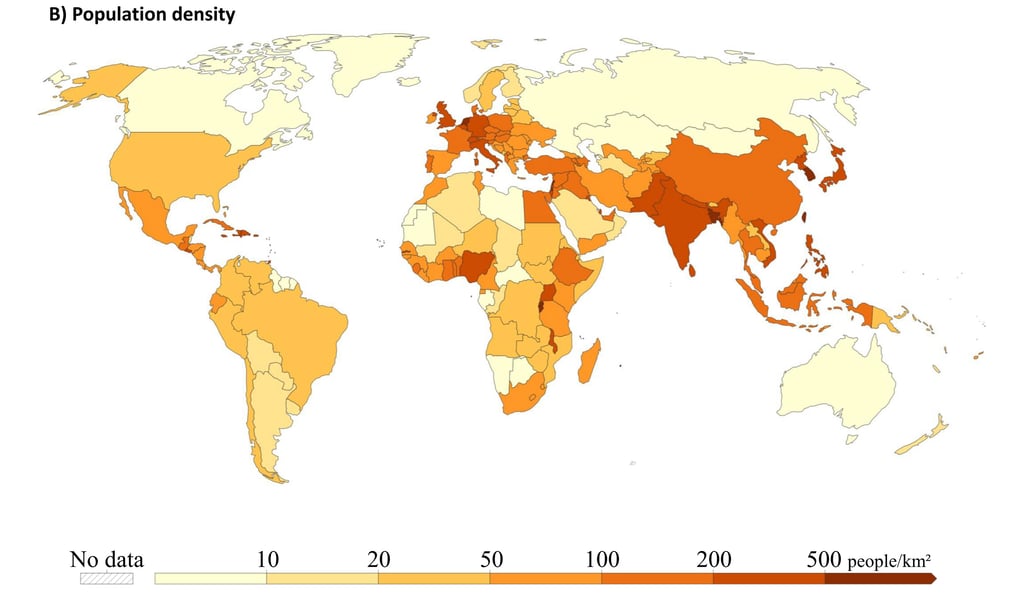

Contrary to popular belief, reducing the population of so-called "rich" (or "developed" or "industrialized") countries would even make sense regardless of lifestyle, since these countries tend to have the highest population densities [7], and not the African countries so often singled out for particularly high population growth (Figure 7)!

Figure 7: World map of annual population growth rate (top) and population density by country (bottom) in 2023. While African countries tend to have high population growth rates, overall population density remains lower than in some European or South-West Asian countries. Source: Modified from Our World In Data (https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth) [7].

A time bomb?

Let's be honest, leaving behind the deadly myth of economic growth and the underlying thermo-industrial model will in no way guarantee the establishment of an economy in harmony with planetary limits and the creation of an "ecological civilization". In the past, lifestyles not based on industrial accumulation have had very strong environmental impacts, as witnessed by the age-old degradation of forest cover in France.

In some "poor" countries, population growth is accompanied by a sharp increase in agricultural land at the expense of forests to meet the food needs of the new arrivals (or to exploit resources in "developed" countries). When changes in land use are included, GHG emissions per capita become high even in some African countries, notably due to deforestation to extend agricultural land (Figure 8) [4].

Figure 8: World map of CO2 emissions per capita and per country in 2023, including emissions linked to changes in land use. When emissions linked to changes in land use (notably deforestation) are taken into account, even so-called "poor" countries tend to have high emissions. Source: Modified from Our World In Data (https://ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions) [4].

More mouths to feed automatically means more agricultural land is needed, as well as an increase in energy requirements, water use, etc. It will therefore be very complicated to reduce our environmental footprint in a context of brutal secular demographic growth. What is clear, however, is that an equitable reduction in the level of production-consumption, and ultimately the abandonment of the industrial model that supports economic growth, are a sine qua non condition for moving towards a less destructive Anthropocene. If this model is not pursued and generalized, then recent population dynamics are quite simply a time bomb.

References

[1] H. Ritchie, « How have the world’s energy sources changed over the last two centuries? », Our World In Data, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/global-energy-200-years

[2] M. Roser, B. Rohenkohl, P. Arriagada, J. Hasell, H. Ritchie, et E. Ortiz-Ospina, « Economic Growth », Our World In Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/economic-growth

[3] H. Ritchie, P. Rosado, et M. Roser, « Energy », Our World In Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/energy

[4] H. Ritchie, P. Rosado, et M. Roser, « CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions », Our World In Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions

[5] OXFAM, « Climate equality: A planet for the 99% », 2023. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/climate-equality-planet-99

[6] F. Lebrun, « Barbarie numérique - Une autre histoire du monde connecté », L’échappée, 2024.

[7] H. Ritchie, L. Rodés-Guirao, E. Mathieu, M. Gerber, E. Ortiz-Ospina, J. Hasell, et M. Roser, « Population Growth », Our World In Data, 2023, https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth

Conclusion

The coincidence between population growth and increasing environmental deterioration easily leads us to believe that population size is the major problem and the primary cause of the Anthropocene.

However, when the level of production-consumption is factored into the equation, this interpretation needs to be revised. There is a very clear coincidence between the increase in the level of production-consumption and the increase in environmental deterioration. However, this level of production-consumption differs fundamentally from one human population to another, which means that different human populations bear different degrees of responsibility for the ecological catastrophe.

In concrete terms, the populations of so-called "developed" countries and the wealthiest individuals within countries bear an overwhelming responsibility, given their disproportionate contribution to resource consumption and waste emissions.

Ultimately, it is the ideology of economic growth and the associated thermo-industrial system which, by making the accumulation of consumables the only desirable and possible collective horizon, emerge as the main causes of the ecological crisis.

With this ideology and system set to persist and become more widespread, population growth - despite being seen more as a consequence of economic growth and industrialization than as a cause of environmental disaster - is a ticking time bomb.

Much more than a hypothetical decoupling of growth and environmental deterioration, the advent of a less destructive Anthropocene requires first and foremost a redefinition of our collective aspirations and a complete overhaul of the associated economic system. When do we start?

Henri Cuny