Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

Anthropocene or Capitalocene?

Is capitalism the primary and only cause of the ecological disaster?

Sometimes, during my talks on the Anthropocene, someone in the audience has stood up and exclaimed, hand on heart: "No, we're not talking about an Anthropocene, but a Capitalocene!" In other words, it would be better to speak of a Capitalocene rather than an Anthropocene, capitalism being the obvious cause of the ecological crisis.

This semantic debate seemed a bit futile to me at first, but I found it fascinating in the end, as it raised questions about the temporality and causes of the Anthropocene. With, in the background, the following questions: was environmental alteration born with capitalism? And is it confined to capitalism?

Grievances against the Anthropocene

The term "Capitalocene", which can already be found in Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptise Fressoz's 2013 book L'évènement Anthropocène [1], has been popularized by Swedish author Andreas Malm [2]. Andres Malm criticizes the concept of the Anthropocene, which would establish the narrative of a homogeneous humanity, composed of individuals equally responsible for the ecological crisis. In so doing, the Anthropocene would depoliticize the debate and fail to highlight the profoundly unequal responsibilities of individuals or populations, these inequalities mirroring the inequities fostered by the capitalist system.

Another criticism of the Anthropocene is that it would make "human nature" the root cause of the ecological crisis, thereby contributing to a certain fatalism in the face of catastrophe, seen as something we can't fight, because it's inherent in who we are. On the other hand, the Capitalocene, by clearly pointing the finger of blame, is a vector for action: in the end, there's nothing inescapable, and all that's needed to solve the problem of environmental deterioration is a thorough reform or, better still, the destruction of capitalism.

So, is the Capitalocene more relevant than the Anthropocene? Does this concept really enable us to better understand the temporality and root causes of the ecological crisis, and thus to identify the levers of action relevant to resolving the problem?

Capitalism as a mode of organization and as a culture

Before answering these questions, let's start by defining the terms. In this article, "capitalism" will refer to the system in which the tool of economic production is owned and controlled by private interests. This system has often been contrasted with communism, in which the economic apparatus is owned and controlled by collective interests.

Like the Anthropocene, capitalism has no clearly defined birth date. Some authors claim it originated in the Middle Ages or earlier, while others propose a birth date around the 15th century [3]. Let's just say that capitalism became widespread from the 18th-19th centuries, particularly in Europe and the United States.

The ultimate goal of capitalism is the accumulation of capital and the pursuit of profit. It is therefore a fundamentally cumulative and productivist-consumerist system, in which the growth of capital and profits is based on the continuous increase in production and consumption. Put another way, capitalism is inseparable from the Holy Grail of modern times: growth as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

In its sanctification of private property and its expansionist aims (symbolized by colonialism in particular), capitalism is also a system of appropriation and exploitation of space and resources (including part of humanity).

Capitalism is, of course, more than just a way of organizing economic production. It is a total system, with its own culture. In this case, a culture of appropriation and privatization of common space and exploitation of nature, a "no-limit culture" [4] of "never enough" and "always more" (permanent dissatisfaction being indispensable to the pursuit of growth), a culture of the commodity that transforms everything into a marketable good or service [5].

All this makes capitalism a designated culprit of the ecological catastrophe, which is highlighted by the concept of the Capitalocene. But before pronouncing a definitive sentence, let us deliberate a little on the subject.

Capitalism dominates CO2 emissions... which are just one small aspect of environmental degradation

In general, proponents of the Capitalocene focus on capitalism's responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. To judge the relevance of this point, let's start by taking a look at cumulative CO2 emissions since 1750.

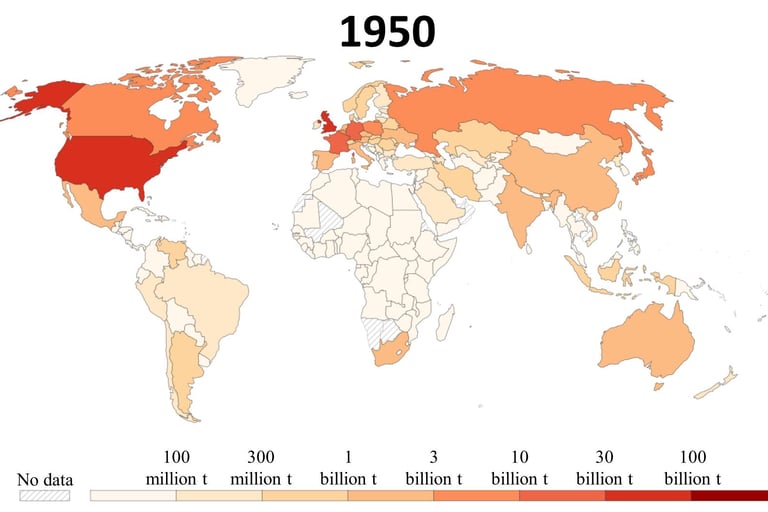

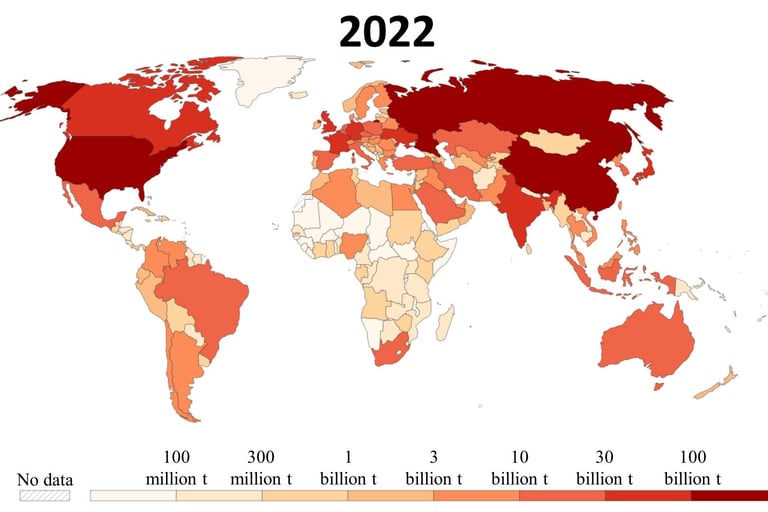

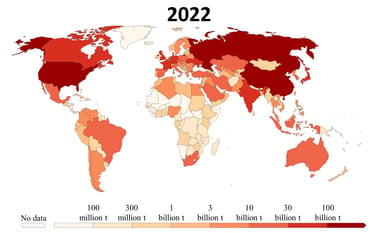

Figure 1: Maps of cumulative global CO2 emissions (from fossil fuels and industry; land-use change is not included) since 1750, by country, in 1950 (left) and 2022 (right). The pioneering countries of capitalism (UK, France, USA...) have historically dominated CO2 emissions, but the contribution of other countries is increasing over time, while countries such as Russia have also had a significant share in CO2 emissions over the course of history. Source: Our World In Data [6].

The result is quite clear: there is an outrageous dominance of capitalist countries in historical CO2 emissions, at least until the middle of the 20th century. In 1950, the United States and the European Union (the current 27 countries plus the United Kingdom, a major contributor) accounted for 75% of cumulative global emissions since 1750 (35% for the USA + 40% for the EU).

However, by 2022, the United States and the European Union account for "only" around 50% of cumulative emissions since 1750 (25% for the USA + 22% for the EU), a share which is of course vastly disproportionate to the size of the corresponding population (around 10% of the world's population in 2022). This decline can be explained by the fact that capitalism has spread to many countries around the world, and that the historic capitalist countries have relocated an increasing proportion of their production to third countries, which is tantamount to relocating their CO2 emissions.

However, we can see that a country like Russia (6% of cumulative emissions since 1750) plays a major role in CO2 emissions. Above all, and this needs to be hammered home, greenhouse gas emissions and climate change are only a small, albeit spectacular and important, part of the process of alteration of the Earth's surface by human activity. And we will now see that, in other respects, human activity has indeed had global and deleterious impacts on the Earth's surface outside of capitalism.

Is environmental degradation the exclusive preserve of capitalism?

Since it is the system most often opposed to capitalism, let's see if communism does better on the environmental front.

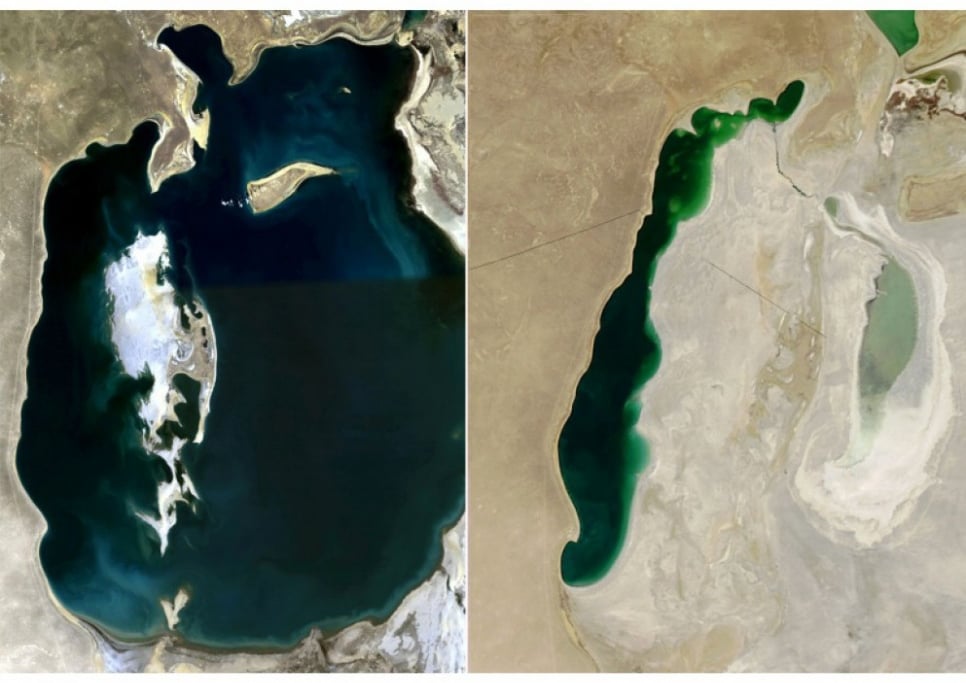

Well, probably not! Soviet megaprojects to divert major rivers to irrigate cotton fields led to the drying up of the Aral Sea, one of the most impressive and terrible environmental disasters of the 20th century!

Figure 2: Satellite images of the Aral Sea in 1989 (left) and 2013 (right). The Aral Sea has been steadily shrinking since the 1960s, after the rivers feeding it were diverted for Soviet irrigation projects. Source: NASA (https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/world-of-change/AralSea ) [7].

The Soviet Union has also contributed to around half of the 2000-plus nuclear tests carried out since the Second World War. Given that radioactive fallout is a particularly important indicator of the Anthropocene, it's fair to say that communism alone has had impacts likely to define a new geological epoch (a Communocene or a Socialocene?)!

With the sole example of the communist USSR, the answer to the question posed in the title of this section is unambiguous: no, environmental deterioration is not exclusive to capitalism, and it's safe to say that two centuries of widespread communism would have led the world into an ecological catastrophe at least as great as the one we're experiencing today.

Did environmental deterioration begin with capitalism?

If, in recent times, environmental alteration has not been the exclusive preserve of capitalist countries, did it exist before the birth and spread of capitalism? Let's cut the suspense short: serious analysis shows that our species did not wait for the advent of big business to alter the planet's surface on a large scale.

We can mention, for example, the major impact on the environment of civilizations such as the Mayas (some authors even speak of a "Mayacene") [8, 9] or the Roman Empire [10, 11]. Impacts of these civilizations include deforestation, extensive exploitation of soil and water, and massive artificialization of water systems, mostly for agricultural purposes. In addition, mining activity and the production of lead and silver by the Roman Republic and then the Empire generated very significant atmospheric heavy metal pollution, which is still detected in numerous natural archives (sediments, animal bones, glaciers, etc.) throughout Europe and beyond [12, 13].

Generally speaking, the deterioration of the environment (and the lack of an appropriate response to this alteration) is recognized as a key factor in the collapse of great civilizations such as the Anasazi of the southwestern United States, the Mayas of Central America or the Vikings of Greenland [14].

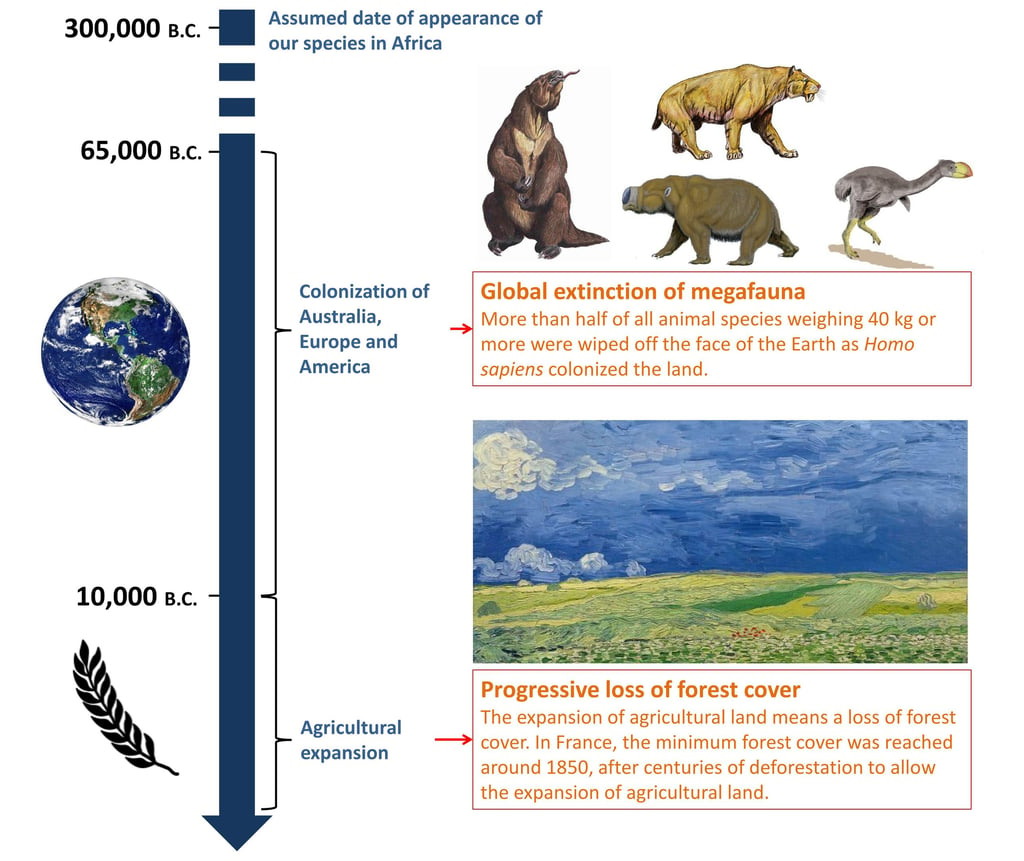

Beyond these examples of significant environmental impacts of certain civilizations, we can identify two more general and spectacular impacts of our species on the Earth's surface dating back several millennia: the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna, during the colonization of the land by our prehistoric ancestors, and the loss of forest cover since the birth of agriculture.

Figure 3: Timeline of the "prehistory" of land surface alteration by Homo sapiens humans, with the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna and loss of forest cover.

The Pleistocene megafauna extinction is a phenomenon that took place between 50,000 and 10,000 years B.C. on all continents of the world: it is estimated that during this period, more than half of all animal species weighing over 40 kilograms disappeared from the Earth's surface [15].

While multi-factorial causes have been suggested (climate change, asteroid impacts...) [16, 17, 18, 19], the preponderance of human influence (through predation and habitat modification) on this extinction is no longer in any doubt [15, 20, 21, 22, 23]. Indeed, the evidence is convincing: all over the world, the extinction of animal species has selectively involved large mammals (where factors other than predation would surely have been less selective) and coincides disturbingly with the supposed dates of land colonization by our species [15].

Tens of thousands of years ago, when the world population numbered only a few million individuals, our ancestors contributed decisively to dramatic and definitive changes in terrestrial animal and plant communities, with the disappearance of many large herbivores having a major impact on ecosystems [24].

Regarding the loss of forest cover, it is estimated that since the beginnings of agriculture (around 10,000 B.C.), the world's forest area has been reduced by at least a third [25] and the number of trees on Earth has been halved [26]. Even if forest loss continues today, its origins can by no means be dated back to the beginning of capitalism.

In France, for example, as in other European countries, the loss of forest area probably beagan as early as 5000 B.C., in parallel with the increase in agricultural land, and continued over successive millennia. The minimum forest cover in France was reached around the beginning of the 19th century. Since then, forest cover has regained ground, mainly as a result of agricultural intensification and the consequent use of fossil fuels, which of course poses other problems.

Ultimately, the answer to the question posed in this section is once again negative and unambiguous: no, environmental deterioration did not begin with capitalism. Past civilizations have had a major impact on the environment. More generally, the Pleistocene extinction (50,000 to 10,000 years B.C.) and the continuing loss of forest cover since the birth of agriculture (as early as 10,000 B.C.) show that alteration of the Earth's surface predates capitalism.

Of course, these impacts are hardly comparable to what we're experiencing today. But the civilizations of the past did not have the transformative (or rather destructive) force that we have, because, not benefiting from the power conferred by fossil fuels, they were more energy-constrained. So ask yourself: what would the Mayas, Romans and so many others have done with the power of fossil fuels? It's easy to shudder at the thought.

A problem of culture rather than a problem of system or human nature

As the preceding sections demonstrate, the alteration of the Earth's surface did not originate with capitalism, nor is it confined to it. This observation presupposes the existence of a kind of "metaproblem", i.e. a problem that would be that of our general relationship to the world and that goes beyond the simple framework of capitalism.

For example, despite the binary opposition of "capitalism vs. communism" that powerfully permeates our minds, communism can in many ways be seen as a mirror image of capitalism, with which it has continually sought to confront and measure itself. The result is a fundamental commonality: the quest for the same goal, namely the expansion of the human empire.

A quest pursued by slightly different but, all in all, relatively equivalent means (fossil-based industrial economy, large-scale exploitation of natural resources, domination of nature...), the main difference lying in the social organization of economic production. Given their many similarities, it's hardly surprising that our two greatest enemies are largely comparable in their relationship with nature.

It seems obvious to me that communism and capitalism were not born on virgin soil, but on fertile ground worked out over millennia, combining a man-nature dualism and a desire to make ourselves "masters and possessors" of a "nature-resource" placed at the disposal of an all-powerful central humanity giving meaning to the world (anthropocentrism and a feeling of superiority over nature).

Ultimately, capitalism seems to be a system fully in tune with this culture rooted in the distant past. In other words, capitalism is perhaps more a consequence of a secular way of thinking than a primary cause of contemporary ecological catastrophe. Capitalism, in turn, reinforces this secular culture, and even builds its own culture of appropriation, exploitation and commodification of the world.

Once we've said that, we understand that the deep-rooted problem is not linked to a system for organizing economic production or to "human nature", but to a way of seeing the world that is deeply rooted in the common imagination. It will therefore not be enough to reform or abandon capitalism in order to enter a "Symbiocene"; we will have to rethink whole swathes of our cultural heritage in order to move towards an imaginary world that does not make human expansionism (or GDP growth) the ultimate goal, and humans the center of gravity of the universe.

The Capitalocene as a narrow perspective of the Anthropocene

Contrary to what its opponents say, I believe that the aim of the Anthropocene concept was never to construct a narrative in which all humans would be equally responsible for the catastrophe, nor to target the "human nature". It is to highlight this staggering fact: a single animal species, ours, and irrespective of the fact that the contributions of each individual of said species are considerably unequal, is causing a major alteration of the Earth's surface, which is a unique event in the 4.5 billion years of the Earth's existence. It seems to me that this constitutes a major and significant event in the planet's history.

To demonstrate this point, let's conduct a thought experiment and imagine living beings in the future, a few million years from now, who, like us, would seek to understand the planet's history. Like us, they would resort to the analysis of stratigraphic layers. They would surely discover the existence of a singular stratum bearing our signature (plastics, nuclear debris, chicken bones, a high number of fossils...). They would then certainly make the link between this singularity and the activity of our species. They would probably understand the decisive role played by fossil fuels (combustion residues, sudden rise in CO2 levels, etc.) in the ephemeral omnipotence of our species. Finally, they might discover that our species was capable of adopting multiple forms of social organization, and that some of these forms (those we call capitalism and communism, for example) were concomitant with the establishment of an environmentally destructive thermo-industrial economy.

From this perspective, it's clear that capitalism is only a detail - albeit an interesting one, and worth noting - in the overall picture painted by the Anthropocene, and not the significant fact that deserves to be brought to the fore.

The Capitalocene as an attempt to make people feel less guilty

Allow me to evoke a personal feeling: I've noticed that, quite often, people who denounce a Capitalocene feel in no way responsible for the ecological catastrophe, while at the same time enjoying many of the goods and services (travel, cars, digital technologies...) offered by the thermo-industrial economy.

And I think that this very personal observation leads me to better understand the craze for the Capitalocene: it is a comfortable concept, because it exonerates us by clearly pointing the finger at a culprit who, of course, is not "us". We return to a kind of binary conception "à la Walt Disney", with the good guys (the "people") and the bad guys (big business, capital...), the former of course having to fight against the latter for the salvation of the world.

And I think this very personal observation leads me to a better understanding of the craze for the Capitalocene: it's a comfortable concept, because it makes us feel less guilty by clearly pointing the finger at a culprit who, of course, isn't "us". We're back to the Walt Disney binary, with the good guys (the "people") and the bad guys (big business, capital...), the former of course having to fight against the latter for the salvation of the world.

By designating impersonal and extrinsic megastructures (nation-states, multinationals, big business...) as the main culprits of the catastrophe, it is therefore possible that the Capitalocene constitutes one of the many strategies of denial and scapegoating, in order to avoid questioning our way of thinking and our way of life.

References

[1] C. Bonneuil et J.-B. Fressoz, L’Évènement Anthropocène – La Terre, l’histoire et nous. Seuil, 2013.

[2] A. Malm, L’anthropocène contre l’histoire - Le réchauffement climatique à l’ère du capital, La Fabrique. 2017.

[3] « Histoire du capitalisme », Wikipédia. Consulté le: 5 juin 2024. https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Histoire_du_capitalisme&oldid=214390319

[4] A. Grandjean, « Pourquoi détruisons-nous la vie sur Terre ? », Chroniques de l’Anthropocène. 2022. https://alaingrandjean.fr/detruisons-vie-terre/

[5] A. Galluzzo, La fabrique du consommateur - Une histoire de la société marchande, La Découverte. 2023.

[6] H. Ritchie, « Who has contributed most to global CO2 emissions? », Our World in Data. 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/contributed-most-global-co2

[7] « World of Change: Shrinking Aral Sea », NASA Earth Observatory. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/world-of-change/AralSea

[8] C. Castanet et al., « Multi-millennial human impacts and climate change during the Maya early Anthropocene: implications on hydro-sedimentary dynamics and socio-environmental trajectories (Naachtun, Guatemala) », Quat. Sci. Rev., vol. 283, p. 107458, 2022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0277379122000890

[9] B. L. Turner et J. A. Sabloff, « Classic Period collapse of the Central Maya Lowlands: Insights about human–environment relationships for sustainability », Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 109, no 35, p. 13908‑13914, 2012. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1210106109

[10] J. D. Hughes et J. V. Thirgood, « Deforestation, Erosion, and Forest Management in Ancient Greece and Rome », J. For. Hist., vol. 26, no 2, p. 60‑75, 1982. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.2307/4004530

[11] L. O’Sullivan, A. Jardine, A. Cook, et P. Weinstein, « Deforestation, Mosquitoes, and Ancient Rome: Lessons for Today », BioScience, vol. 58, no 8, p. 756‑760, 2008. https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/58/8/756/381265

[12] N. Silva-Sánchez et X.-L. Armada, « Environmental Impact of Roman Mining and Metallurgy and Its Correlation with the Archaeological Evidence: A European Perspective », Environ. Archaeol., p. 1-25, 2023. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14614103.2023.2181295

[13] S. Preunkert et al., « Lead and antimony in basal ice from Col du Dome (French Alps) dated with radiocarbon: A record of pollution during antiquity », Geophys. Res. Lett., vol. 46, no 9, p. 4953‑4961, 2019. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2019GL082641

[14] J. Diamond, Effondrement: comment les sociétés décident de leur disparition ou de leur survie. Gallimard, 2006.

[15] H. Ritchie, « Did humans cause the Quaternary Megafauna Extinction? », Our World in Data. 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/quaternary-megafauna-extinction

[16] E. D. Lorenzen et al., « Species-specific responses of Late Quaternary megafauna to climate and humans », Nature, vol. 479, no 7373, p. 359‑364, 2011. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature10574

[17] R. B. Firestone et al., « Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling », Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 104, no 41, p. 16016‑16021, 2007. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0706977104

[18] A. D. Barnosky, P. L. Koch, R. S. Feranec, S. L. Wing, et A. B. Shabel, « Assessing the causes of late Pleistocene extinctions on the continents », Science, vol. 306, no 5693, p. 70‑75, 2004. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1101476

[19] J. M. Broughton et E. M. Weitzel, « Population reconstructions for humans and megafauna suggest mixed causes for North American Pleistocene extinctions », Nat. Commun., vol. 9, no 1, p. 1‑12, 2018. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-07897-1

[20] F. Saltré et al., « Climate change not to blame for late Quaternary megafauna extinctions in Australia », Nat. Commun., vol. 7, no 1, p. 1‑7, 2016. https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms10511

[21] M. E. Allentoft et al., « Extinct New Zealand megafauna were not in decline before human colonization », Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 111, no 13, p. 4922‑4927, 2014. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1314972111

[22] G. Haynes, « North American megafauna extinction: Climate or overhunting », Encycl. Glob. Archaeol. N. Y. Springer, p. 5382‑5390, 2016. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_1853

[23] S. Van Der Kaars et al., « Humans rather than climate the primary cause of Pleistocene megafaunal extinction in Australia », Nat. Commun., vol. 8, no 1, p. 1‑7, 2017. https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms14142

[24] S. Rule, B. W. Brook, S. G. Haberle, C. S. Turney, A. P. Kershaw, et C. N. Johnson, « The aftermath of megafaunal extinction: ecosystem transformation in Pleistocene Australia », Science, vol. 335, no 6075, p. 1483‑1486, 2012. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1214261

[25] H. Ritchie, F. Spooner, et M. Roser, « Forests and Deforestation », Our World Data. 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/forests-and-deforestation

[26] T. W. Crowther et al., « Mapping tree density at a global scale », Nature, vol. 525, no 7568, p. 201‑205, 2015. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14967

Conclusion

As you will have gathered from reading this article, my assessment of the Capitalocene concept is more than mixed. By narrowing the spectrum of analysis too much, the Capitalocene poorly describes the complexity and temporality of the alteration of the Earth's surface by our species. A historical and global approach shows that, although capitalism accounts for the lion's share of the contemporary ecological disaster, it does not appear to be the primary and sole cause of the catastrophe.

In fact, rather than being a cause, it may well be the consequence of a way of thinking that has its roots in the distant past and which, by making humans the center of everything, with the desire to control a nature placed at disposal and to grow indefinitely, can only generate a system at war with the "non-human".

That said, the Anthropocene, like any concept, is fundamentally simplistic and therefore imperfect. Too global, it can actually lead one to believe that all humans bear equal responsibility for the alteration of the Earth's surface, which is dramatically false. However, unlike the narrow approach of the Capitalocene, it is possible to start from the generality of the Anthropocene and then delve deeper into the question, by deconstructing the phenomenon in all its complexity. A more detailed analysis, in which capitalism will of course have its rightful place.

Henri Cuny