Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

Anti-ecomodernism volume 3: It's not enough to call yourself modern to be modern

Why techno-solutionism is nothing modern

Today, many people believe that technology can make us more virtuous and respond to challenges such as “the fight against climate change”. These techno-solutionists often claim to be modernists, while condemning those who think differently (i.e. those who have reservations about the technological solution) as vile reactionaries who want to return to the dawn of times.

Among them are the likes of Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, French President Emmanuel Macron and French Minister Bruno Le Maire, who have no words harsh enough to describe those who question our development model [1, 2, 3]. Similarly, the self-proclaimed “ecomodernists”, fervent techno-solutionists, assert their modernity right down to the name of their movement (ecomodernism, that is).

In this article, I propose a reflection on the so-called modernity of using technology to “improve” our relationship with nature. But before getting to the heart of the matter, what does it mean to be modern?

What does being modern means?

According to Wikipedia (France), “modernity is a concept that refers to the idea of acting in accordance with the times, rather than according to values that are considered de facto outdated. [...] Closely linked to ideas of emancipation, growth, evolution, progress and innovation, the concept of modernity is the opposite not only of ideas of immobility and stagnation, but also of ideas of attachment to the past (tradition, conservatism...): to be modern is first and foremost to be forward-looking.” [4]

Modernity is therefore assessed in relation to the past, and assumes that the present state is better than an older state, and that tomorrow will be even better. In other words, being modern implies a break with a past that was judged negatively in terms of conceptions and behavior.

Let's turn to the question at hand: does being a techno-solutionist make you modern?

From a material point of view, techno-solutionism is modern

If we look at things from a purely material angle, we might be inclined to say that techno-solutionists (including eco-modernists, that is) are indeed modern. After all, don't they advocate innovation and the use of the latest technologies to "solve the environmental crisis"? In a way, these people "live with the times", as they say, and see contemporary developments as obvious means of progress. We can do better today and tomorrow than we did yesterday, and this improvement is due in particular to the latest technologies, which are "cleaner" and more efficient than those of the past.

However, is being fond of current material means, such as new technologies, enough to make you a modern person? If you're a connoisseur and passionate user of new technologies but subscribe to archaic conceptions on a host of subjects (women's place in society, children's education, etc.), will you be deemed "modern"? Probably not, since being modern perhaps implies above all subscribing to a vision of the world that is not that of the distant past.

Clearly, then, if techno-solutionists are characterized by their appetite for new technologies, this is not enough to qualify them as modern; to do so, we need to look at the major conceptions that drive them.

In its philosophical foundations, techno-solutionism is an archaism

To understand the worldview of the proponents of the technological solution and to judge its modernity, let's start by listing the three main ideas at the heart of techno-solutionism

Nature must be mastered through science and technology;

Man is separated from nature;

Natural resources are unlimited.

I've already shown in another article that idea number 3 is irrational, and I won't go back over whether it's modern or not, even though the hypothesis of unlimited resources was already apparent in the 19th century [5]. Here, for example, is what Jean-Baptiste Say stated in his "Cours complet d'économie politique pratique", in 1828-1830: "Natural wealth is inexhaustible, for without it we would not obtain it for free. Since they can neither be multiplied nor exhausted, they are not the object of economic science." [5]

Let's take a look at ideas 1 and 2 to see how modern they are.

Past vision n°1: Mastering nature through science and technology

Achieving a decoupling between human development and environmental alteration is at the heart of the project of techno-solutionists being precisely the "magic wand" that will make this decoupling possible. This ambition was formulated early on in the ecomodernist manifesto [6]:

“As scholars, scientists, campaigners, and citizens, we write with the conviction that knowledge and technology, applied with wisdom, might allow for a good, or even great, Anthropocene.”

Or just after:

“[…] modern technologies, by using natural ecosystem flows and services more efficiently, offer a real chance of reducing the totality of human impacts on the biosphere. To embrace these technologies is to find paths to a good Anthropocene. ”

I've already mentioned the fact that such a decoupling is perfectly hypothetical today, and is in no way supported by the facts. Summaries of current knowledge have shown that, at this stage, there is no serious decoupling between economic growth and environmental deterioration, and, above all, that the occurrence of such a decoupling is highly unlikely in the short term [7, 8].

Aside from its illusory nature, the ambition of decoupling through technology is symptomatic of a technicist civilization of scientists and engineers, which views all problems in terms of the technical challenge to be solved, without ever questioning the underlying causes of said problems. Climate change, for example, is explicitly formulated in the ecomodernist manifesto as nothing more than a technical problem to be solved, and in no way the result of a development model (for example, burning insane amounts of energy to produce and consume ever more, and thus increase GDP):

“Meaningful climate mitigation is fundamentally a technological challenge.”

Obviously, this idea of using science and technology to improve the human condition goes hand in hand with an ideal of mastery and domination of nature:

“A good Anthropocene demands that humans use their growing social, economic, and technological powers to make life better for people, stabilize the climate, and protect the natural world.”

Thanks to our knowledge and skills, we're going to stabilize the climate and protect nature, which presupposes the expression of incredible mastery (to control the climate) and hegemony (with nature now under human's protection).

Let's not make the mistake of believing that this way of thinking is reserved only for a few radical "technophiles": it lies at the heart of our civilization. For example, sustainable management is the contemporary paradigm of humans as the great masters of nature, of which they are the manager and enjoyer. Through the subtle application of our knowledge, we are going to "manage" nature, by "regulating" the populations of "harmful" and "useful" species, by "managing" biogeochemical flows (carbon in particular) on the basis of detailed accounting, by "adapting" ecosystems to climate change, etc. The time has come for "irresponsible scientists to the empire of an emerging geopower, which reconceptualizes the Earth as a system to be known and managed in order to extract the maximum sustainable yield from it." [9]

The idea that science and technology should be used to control nature and thus make mankind all-powerful is a dominant paradigm of our time. But is it modern? In other words, does the belief in using science and technology to control nature and thus increase human power constitute a philosophical break with past beliefs?

Clearly not! The 17th century, for example, a century of scientific emancipation, was deeply marked by the propagation of the idea that knowledge and technology were vectors of progress and power, because they enabled us to master nature. Francis Bacon, for example, is considered a founding father of science as it is still practiced today:

“But if a man endeavor to establish and extend the power and dominion of the human race itself over the universe, his ambition (if ambition it can be called) is without doubt both a more wholesome and a more noble thing than the other two. Now the empire of man over things depends wholly on the arts and sciences. For we cannot command nature except by obeying her.” (Francis Bacon, Novum Organum, 1620)

In the same vein, Francis Bacon would have said that "scientia potentia est" (knowledge is itself power)". The idea of using science and technology to increase human power and dominate nature is already clear.

René Descartes takes the idea of controlling and appropriating nature through science and technology a step further, as he explains in this text, including the famous call to "make ourselves as lords and possessors of nature":

“For by them I perceived it to be possible to arrive at knowledge highly useful in life; and in room of the speculative philosophy usually taught in the schools, to discover a practical, by means of which, knowing the force and action of fire, water, air the stars, the heavens, and all the other bodies that surround us, as distinctly as we know the various crafts of our artisans, we might also apply them in the same way to all the uses to which they are adapted, and thus render ourselves the lords and possessors of nature.” (René Descartes, Discourse on the Method, 1637)

Descartes thus already postulated the arrival of a humanity that would become master of nature thanks to knowledge. In the 19th century, Descartes' Promethean ambitions were echoed in "Laplace's demon", which opened the way to the possibility of total and absolute control of nature through knowledge:

“An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past could be present before its eyes.” (Pierre-Simon Laplace, A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, 1814)

Shortly afterwards, Auguste Comte endorsed the idea of knowing nature in order to gain control over events:

“The aim of every science is foresight (prevoyance). For the laws of established observation of phenomena are generally employed to foresee their succession. All men, however little advanced make true predictions, which are always based on the same principle, the knowledge of the future from the past.” (Auguste Comte, Cours de philosophie positive, 1828-1842)

A quotation often summed up by phrases like “From science comes foresight, from foresight action.” or "To know is to foresee, to foresee is to have power". We need to know nature, because this knowledge is a source of power. This attitude is reflected in the two great 18th-century attempts to inventory nature, by Carl von Linné with his Systeme Naturae (1735) and Buffon with his Histoire naturelle (1749).

Figure 1: The idea of mastering nature through science and technology propagated by Francis Bacon (1561-1626; left), René Descartes (1596-1650; middle) and Auguste Comte (1798-1857; right) still has a powerful influence on today's minds. It's not for nothing that these three figures are considered the founding fathers of the modern scientific method. But should ideas formulated centuries ago be considered modern?

Clearly, then, the idea of using knowledge (acquired through science) and its practical application (through technology) to master nature can in no way be described as modern. The idea was already widely formulated in the 17th century and perhaps earlier, though its precise origin remains difficult to determine. However, we can assume that the great scientific advances of the time - notably the heliocentric model proposed by Copernicus in the early 16th century, and the subsequent work of Bruno, Galileo, Kepler and Newton - played a fundamental role in the emergence of a shared vision of an all-powerful science as a source of knowledge and mastery of the world. It's a vision that still permeates people's minds today, but one that is nonetheless centuries old.

Past vision n°2 : Man is separated from nature

Subscribing to the idea that we can "tame" nature by knowing it better rests on another postulate: that we are not part of nature. This man-nature dualism is very much in evidence in the ecomodernist manifesto:

“The modernization processes that have increasingly liberated humanity from nature...”

Or further:

“[…] we reject another [ideal], that human societies must harmonize with nature to avoid economic and ecological collapse.”

Or again:

“The role that technology plays in reducing humanity’s dependence on nature explains this paradox. Human technologies, from those that first enabled agriculture to replace hunting and gathering, to those that drive today’s globalized economy, have made humans less reliant upon the many ecosystems that once provided their only sustenance, even as those same ecosystems have often been left deeply damaged.”

Reading these passages, the dualism between man and nature is clear: thanks to knowledge and technology, humans have “extracted” themeselves from nature, from which they now evolves independently, and which they no longer fundamentally needs.

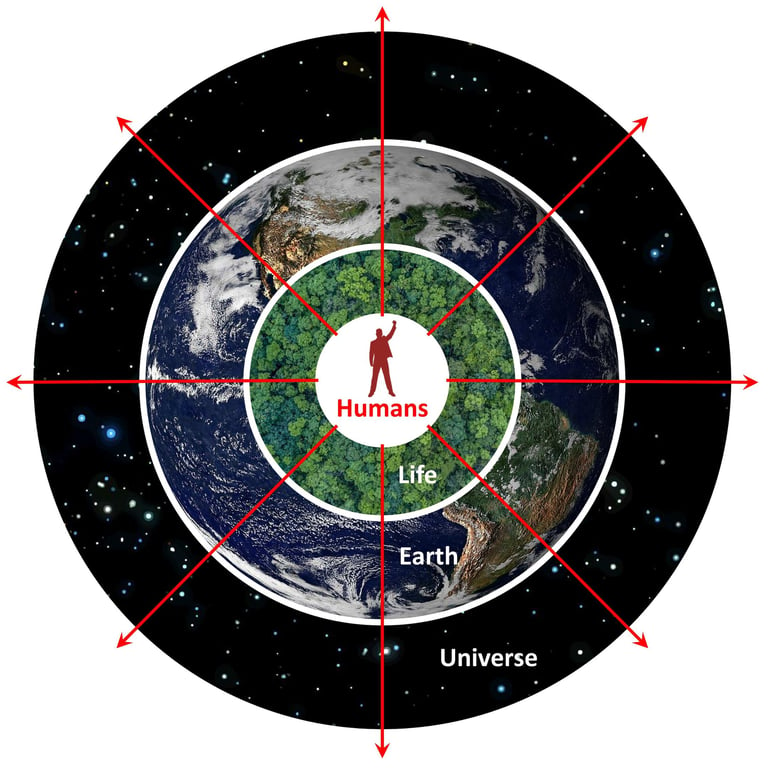

This man-nature dualism actually incorporates two key concepts: anthropocentrism and the superiority of humans over nature.

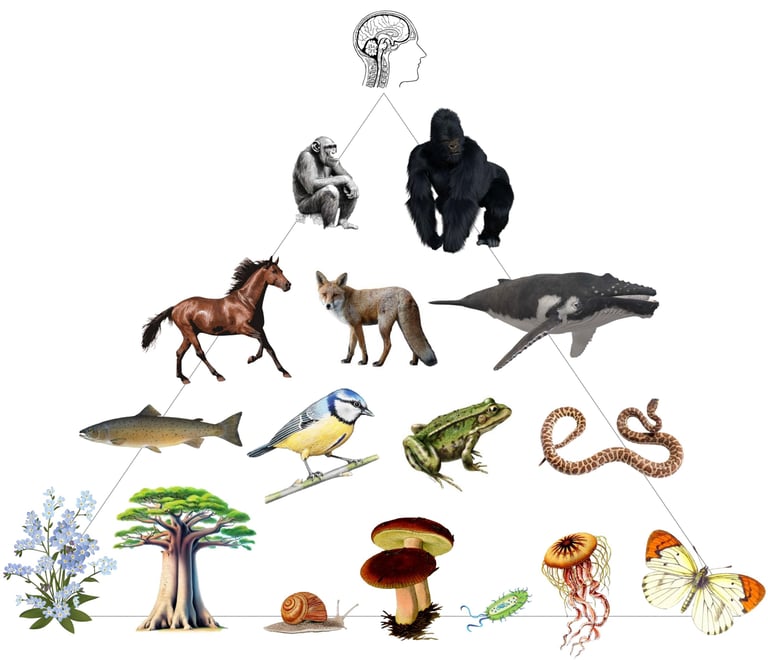

Figure 2: Man-nature dualism integrates two fundamental concepts at the heart of contemporary thought, with A) anthropocentrism, according to which humans are at the center of everything and give meaning to the world, and thus have a duty to extend their empire as far as possible, over other living beings, the Earth and even the entire Universe, and B) the superiority of man over nature, the human spirit in particular being what elevates humans over other living beings, whom they must dominate (today, we say manage or regulate, but the aim is of course the same).

A) Anthropocentrism

B) Superiority

This dualism (and thus anthropocentrism and the idea of human superiority) is at the heart of our civilization (cf. the sustainable management paradigm mentioned above, but also geo-engineering of course, or the placing on a pedestal of humanism, which is pure anthropocentrism, ...), to such an extent that we no longer even realize it. It is, however, in no way modern, and has its foundations in the distant past.

For example, it's abundantly clear from the various quotations in the previous section. With the establishment of an all-powerful and beneficent technical mythology comes the development of a mechanistic vision of nature, which is now seen as "a book written in mathematical language", to quote Galileo. The rise of this mechanistic vision led to a "disenchantment of the world", to use Max Weber's expression, and to the idea of a "nature-object" separated from "human-spirit" and capable of being "mastered" by the latter.

Man, a being endowed with intelligence and reason, places himself above nature, which is no more than a cold, mechanical setting, a disenchanted world whose secrets can be penetrated by the mind. In this way, a vertical relationship develops between a demiurgic humanity that gives meaning to the world, and an inert object-nature that must be understood.

The man-nature dualism is therefore ancient, and certainly predates the idea of the control of nature by science and technology, since it is a prerequisite for it (it's hard to imagine mastering/controlling/dominating something you feel part of). This is very much the case in the dominant monotheisms, all of which place nan as God's ultimate creation, to whom nature, as a kind of inanimate scenery, is made available*. And so it is in this oft-repeated passage from the Bible:

“Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”

Taken literally, the text is explicit: it is man's duty to dominate and govern the other elements of the Earth.

In a now-famous text, Lynn White singled out Christianity in particular as the main cause of ecological disaster, not least because of its ultimate anthropocentrism [10]. By contrast, we can assume that monotheistic texts are merely reflections of the dominant thinking of the time, i.e. more the consequence than the cause of a way of thinking. Indeed, it may be giving them far too much importance to believe that these texts have totally revolutionized our way of seeing the world, as if they were divine emanations suddenly guiding humanity towards a new path. No, they are perhaps above all mirrors of their time. In which case, monotheistic religions should be seen as integrators and propagators of anthropocentrism and man's superiority over nature, rather than as the origin of these conceptions.

In this sense, it is likely that man-nature dualism was born long before the emergence of monotheism. For example, the development of agriculture from around 10,000 BC onwards can be seen as a major factor in the emergence of a way of thinking that dissociates man from nature. "Sedentarization and domestication go hand in hand with the establishment of clear boundaries between the human world and the outside world. When you spend the majority of your life in an environment that you shape exactly to your wishes and that separates you from the outside world, you extract yourself from the world. Man is no longer an element of the natural cosmos subject to nature's constant changes. He becomes an element that shapes nature to his will. There's a total reversal in the man-nature relationship: it's no longer man adapting to nature, but nature adapting to man." [11]

As all the above elements demonstrate, the man-nature dualism is very old, and still powerfully permeates people's minds. Yet, like geocentrism in its day, it has been largely undermined by science over the last two centuries.

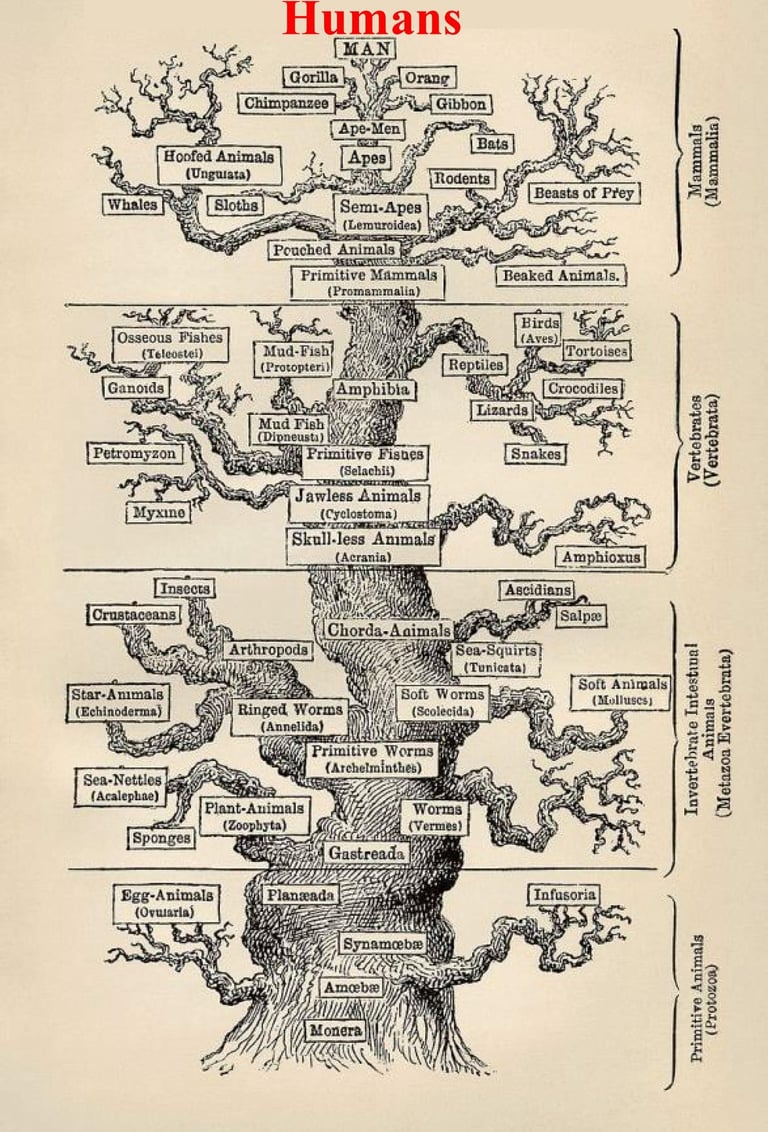

As early as 1849, Charles Darwin, with his theory of evolution published in The Origin of Species [12], demonstrated what may still be a scoop to some today: man, like the millions of other living beings with which he coexists on Earth, is the product of a long process of diversification of life, and not a superior being suddenly appearing in a natural setting tailor-made to ensure his contentment. This revelation, however, did not put an end to the vision of man enthroned over the rest of life, as shown by the phylogenetic trees published after The Origin of Species.

Figure 3: Haeckel's 19th-century phylogenetic tree (1879). Man sits at the pinnacle of evolution, dominating the rest of the living world. This tree, which predates the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species (1849), bears witness to an anthropocentrism and sense of human superiority over nature that still prevails today. Source: Wikipedia [13].

Advances in genetics and ecology in the 20th century confirmed what Darwin's theory postulated: living beings are all linked, through filiation and interdependence. And man is an integral part of this whole. So it's not man on one side and the rest of the living world on the other, but billions of related species that need each other to live together on this planet.

Finally, the Anthropocene dashboard also proves that there are no “human systems” on one side and “natural systems” on the other, but rather a total interdependence between human activity and the Earth's trajectory [14]. Human activity is abusing the Earth's surface and "non-humans" to produce and consume ever more, and this over-exploitation is taking its toll by altering planetary habitability and causing a general decline in living things.

The conclusion of this section is crystal-clear: the man-nature dualism is a concept that dates back to time immemorial, and one that ignores contemporary knowledge of the interdependent relationships and filial ties between the multiple forms of life that inhabit the Earth's surface, with man as one form of life among the others. Under these conditions, it's hard to describe techno-solutionism or eco-modernism, movements that are rooted in dualism, as modern.

Références

[1] « Macron se moque des défenseurs du « modèle amish » au détriment de la 5G », 20 minutes. https://www.20minutes.fr/high-tech/2861835-20200915-5g-macron-moque-defenseurs-modele-amish-detriment-nouvelle-technologie

[2] « Bruno Le Maire sur LinkedIn : Croissance et climat sont compatibles ! Je ne crois pas à l’idéologie de la décroissance et je la combattrai ». https://fr.linkedin.com/posts/brunolemaire_croissance-et-climat-sont-compatibles-je-activity-7138060226502512641-l4yR

[3] A. Piquard, « Jeff Bezos rêve d’envoyer l’humanité dans l’espace », Le Monde, 2021. https://www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2021/06/11/jeff-bezos-reve-d-envoyer-l-humanite-dans-l-espace_6083678_3234.html

[4] « Modernité », Wikipédia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Modernit%C3%A9&oldid=212161853

[5] J.-B. Say, Cours complet d’économie politique pratique, Tome 1. Paris: Guillaumin, 1832.

[6] J. Asafu-Adjaye, L. Blomqvist, S. Brand, B. Brook, R. Defries, et E. Ellis, « An ecomodernist manifesto », 2015. http://www.ecomodernism.org/manifesto-english

[7] T. Parrique et al., « Decoupling debunked: Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. European Environmental Bureau. », 2019. https://eeb.org/library/decoupling-debunked/

[8] H. Haberl et al., « A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights », Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 15, no 6, p. 065003, 2020. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a

[9] A. Saint-Martin, « Bonneuil (Christophe), Fressoz (Jean-Baptiste), L’événement anthropocène. La terre, l’histoire et nous, Paris, Le Seuil, coll. “Anthropocène ”, 2013, 304 pages. », Politix, vol. 111, no 3, p. 202‑207, 2015. https://www.cairn.info/revue-politix-2015-3-page-202.htm

[10] L. T. White, Les racines historiques de notre crise écologique. Presses Universitaires de France, 1967.

[11] H. Cuny, Le bon, la brute et le tyran - Ce que l’Anthropocène dit de nous. Maïa, 2023.

[12] C. Darwin, L’origine des espèces : Au moyen de la sélection naturelle ou la préservation des races favorisées dans la lutte pour la vie. 1949.

[13] « Arbre phylogénétique », Wikipédia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arbre_phylogénétique

[14] W. Steffen, W. Broadgate, L. Deutsch, O. Gaffney, et C. Ludwig, « The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration », Anthr. Rev., vol. 2, no 1, p. 81‑98, 2015. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2053019614564785

Conclusion

Ultimately, an analysis of the past highlights the age-old development of two interconnected conceptions that are still fundamental to our current relationship with the world:

A man-nature dualism, characterized by radical anthropocentrism and a feeling of superiority; a conception probably fostered by the rise of agriculture over 10,000 years ago, then propagated by the great monotheisms in particular.

A will to control Nature through science and technology, an idea asserted and disseminated by illustrious scientists and philosophers from the 16th century onwards.

These two conceptions are at the heart of our civilization today. In particular, they are shared by advocates of the technological solution such as eco-modernists, as well as by the vast majority of "world leaders" (politicians, business leaders, etc.). The question I would like to put to you is quite simple: should we continue to consider as modern a development model based on a man-nature dualism that goes back thousands of years, and on a centuries-old deification of science and technology?

Henri Cuny

Notes

*While it's common to think of science and religion as head-on opposites on a whole host of subjects (a view of course fuelled by the tumultuous relationship between science and religion since the 16th century), when it comes to the man-nature dualism, science can be said to be the spiritual daughter of monotheistic religions.