Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

Are there too many of us on Earth? Part 1: Coincidence

When population growth coincides with increased Earth's alteration

Neighbourhood of Jalousie near Port-au-Prince in Haiti. Image source: Global Population Speakout (https://populationspeakout.org/).

The concept of overpopulation is undeniably tricky. How do you define overpopulation? Answering this question inevitably leads to another equally perilous one: what is an adequate or optimal population?

After all, population is what it is, and if there are eight billion Homo sapiens on Earth today, it's because conditions have made this indisputable fact possible. How, then, can we claim that this is too many and that it is imperative to reduce it? Or conversely, that it's not enough and that we need to grow even more? And by how much should we decrease, or by how much should we increase?

Determining whether or not the planet is overpopulated is therefore a delicate exercise. One way of approaching the question is to assess the adequacy between the current population and the vital support of our existence, the biosphere.

This adequacy will be addressed in the different parts of this article, with :

The surface of land we occupy (“Is the house big enough?” below);

The general state of the environment (“What's the condition of the house?”);

The quantity of resources used (“What about the pantry?”);

Our relationship with the other forms of life (“What does the neighborhood have to say about this?” and “What place does the human species have in the family of living beings?)

Is the house big enough?

As we saw in the previous article, the Homo sapiens family has undergone an unprecedented expansion in recent decades. Since there are more and more of us, a natural first question might be whether there's enough room for everyone on Earth. To understand this, we can look at population density, defined as the number of Homo sapiens human inhabitants* per unit area of land (usually square kilometers, km²).

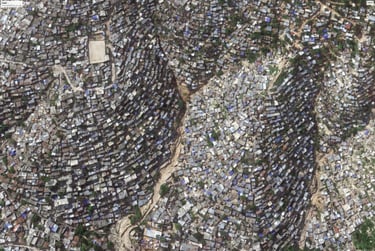

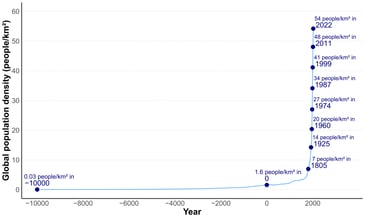

Between 10,000 BC and today, average population density has increased almost 2,000-fold, from 0.03 inhabitants/km² to around 55 inhabitants/km² (Figure 1). So there are obviously more and more of us per unit area of land.

Figure 1 : Changes in global population density (number of humans per square kilometer of land area) over the past 12,000 years. Source of data: Our World In Data for global population (https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth#explore-data-on-population-growth) [1], divided by land area (148 million km²).

However, this overall average masks colossal disparities. While population density is very low in some places (e.g. less than 5 inhabitants/km² in Canada, Australia or Mongolia), it reaches very high values in others (around 500 inhabitants/km² in India or South Korea; Figure 2).

Figure 2 : Population density per country in 2025. Source of the map: Modified from Our World In Data (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/population-density) [1].

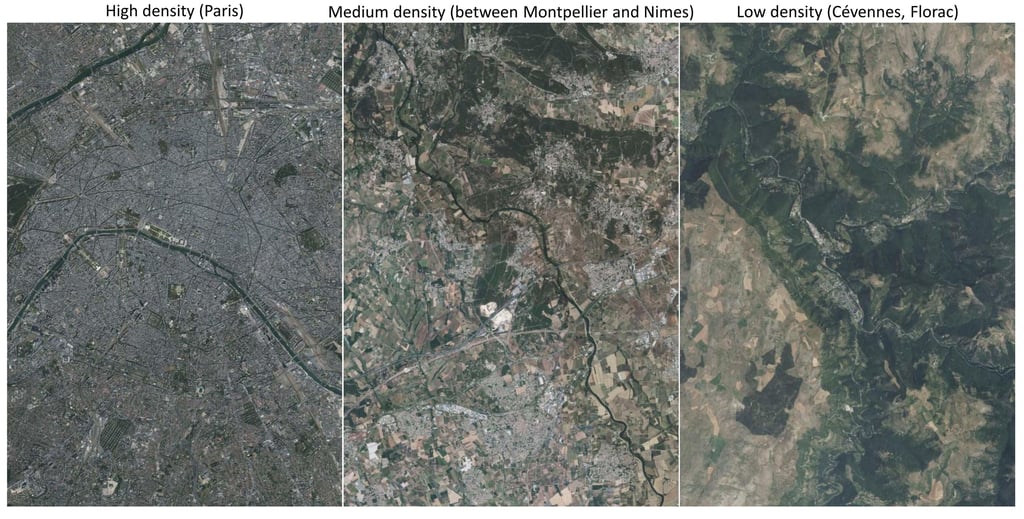

In fact, 95% of the world's population is concentrated on just 10% of the planet's land surface [2], and even within a single country, extremely varied population densities can be observed (Figure 3).

Figure 3 : Aerial photographs illustrate the variability of population density in France, with a high-density area (Paris), a medium-density area (southern France, between Montpellier and Nîmes) and a low-density area (Cévennes). Source of images: IGN - Géoportail (https://www.geoportail.gouv.fr/carte).

Dantesque population densities are sometimes even reached locally (for example, over 20,000 inhabitants per km² in Paris [3]). Which leads some people to think that, after all, there's more space on Earth than there needs to be [4].

Think about it: with a population density close to that observed in Paris (around 20,000 inhabitants/km²), the whole of humanity could fit on 400,000 km², an area smaller than that of metropolitan France (around 545,000 km²), which itself represents only 0.4% of the total land area on Earth! Clearly, available space does not seem to be an obstacle to current population levels, or even to sustained growth.

The problem is that, in reality, population density is a highly irrelevant indicator of the space we occupy, or, more generally, of whether there's enough room for the current population or even for more humans. Indeed, housing is just one of the many ways in which we occupy space.

Take the example of another vital aspect of our activity, food production: today, agriculture occupies around 40% of the Earth's landmass and almost half of the planet's habitable land! In other words, just to feed ourselves, our species alone takes up half the earth's surface area, most of the time in a tyrannical fashion (just think of those immense cereal monocultures)!

So, the possibility of fitting the whole of humanity on the French territory says nothing about the place actually occupied by human activity: whatever the place taken by the habitat, considerable surfaces are mobilized to provide the resources and energy necessary for human activity, and even very sparsely populated areas are in fact anthropized to the extreme (cf. Figure 3, in which the human stranglehold on the Earth's surface is obvious even for less populated areas).

What is clear is that, just looking at the land surface occupied, the figures and dynamics speak in favor of human excess: a single species, among the millions of species inhabiting the Earth, is taking over the majority of the Earth's surface for its own benefit (habitat, transport, agriculture, resource extraction, etc.). From this point of view, the Anthropocene is indeed a time of human tyranny [5].

Above all, the amount of land occupied is only one aspect of human activity, and so we need to broaden the scope of our analysis to assess its impact on the biosphere, otherwise we risk falling back into the simplistic reasoning typical of ecomodernism. Greenhouse gas emissions, for example, are not directly linked to the land area occupied by human activity, but are a crucial criterion for assessing the impact of our population on the Earth's habitability.

What's the condition of the house?

In addition to the size of the house, you also need to consider its condition and that of its surroundings. If you have a huge house, but you've ravaged it to the point of insalubrity, the air inside is unbreathable, the water is no longer drinkable and the garden looks like a minefield, it's likely that the house, however large, can no longer fulfill its function as a home.

And in this respect, unfortunately, most of the available indicators point to an advanced state of decay! Greenhouse gas concentrations, surface temperatures and sea levels are all rising sharply, eternal pollutants are everywhere [6, 7], and water in many parts of the world is in short supply and polluted to the point of being unfit for consumption [8], air pollution is causing the premature death of millions of people worldwide [9, 10], the populations of many “non-human” animal species are collapsing [11, 12], the extinction rate of “non-human” species is soaring [13, 14]... The cup is full!

In fact, human population growth over the last few decades coincides in a disturbing way with the increase in alteration of the Earth's surface. For example, there is an extremely strong correlation between human population size and greenhouse gas emissions (Figure 4).

What does the neighborhood have to say about this?

Another aspect I feel is important to consider is our relationship with our neighbors. As mentioned earlier, our species is just one of the countless life forms that inhabit the planet. And, unfortunately, our relationship with the many forms of "non-human" life is, on the whole**... conflictual. Rather tyrannical or despotic, in fact, since it can be summed up in two words: exploitation and destruction, with one tragic end in sight: the extinction of living things.

Just remember this staggering figure: every year, humans kill over a thousand billion animals to feed, clothe and care for themselves [17]. So, from a "biocentric" point of view (if that makes sense), it seems that human population growth constitutes a tragic fate for the majority, as the life form that tends to annihilate others prospers.

What place does the human species have in the family of living beings?

The question of population size can also be approached from a more metaphysical angle, depending on how we view our place in the living world and on Earth. In concrete terms, our growing numbers mean that we tend to occupy all space, leaving only crumbs for the countless other forms of life on the planet.

From an anthropocentric point of view, such as that of the monotheisms that more or less clearly call for the human species to dominate the world, recent trends in the human population are surely perceived positively. Considering what we know about the path of life since its beginnings, this is quite questionable. Life has evolved over billions of years to generate ever more numerous, complex and interdependent forms. From this perspective, there's nothing natural or desirable about a single form of life maintaining such hegemony over the others.

What about the pantry?

We also have to take into account what we consume. If we have a huge house, but the pantry is empty, it can quickly become a scramble! Here too, unfortunately, the signs are that we tend to consume more than nature can replenish. Here too, human population growth clearly coincides with increased resource consumption, as shown by the almost perfect correlation between population size and primary energy consumption (Figure 4).

Unfortunately, the signs are that we tend to consume more than nature can replenish. A well-known indicator is the "Earth Overshoot Day", calculated by the American NGO Global Foortprint Network and supposed to define the day of the year after which we are living on credit (i.e. beyond which what we consume in resources or produce in waste exceeds what is annually produced or absorbed by nature). This Earth Overshoot Day is constantly being brought forward in time: it occurred in December in the 1970s and has been defined as August 1 in 2024 [15].

This indicator is, however, the subject of considerable criticism [16]. So let's concentrate on a few irrefutable facts which show that the resources on which our activity is based are becoming poorer. For so-called “non-renewable” resources (oil, gas, coal, various metals, etc.), which form the bedrock of our civilization (and of population growth), reserves are difficult to quantify, but are by definition diminishing, since they cannot be replenished on the timescales we are concerned with.

Above all, in order to sustain an economy of accumulation and by no means of transition, we are consuming ever more of these resources, which means that they are running out faster and faster. The digital race in particular, which has been underway for decades but is accelerating even further with the frenetic and reckless AI craze, is putting unsustainable pressure on many resources, including metals.

As far as “renewable” resources are concerned, we can simply mention the terrible loss of forest cover that has been taking place since the birth of agriculture, as well as the decline in animal populations, for example in a growing number of fish species. Living things generally tend to collapse under the influence of human activity, which is certainly the most alarming sign of the excesses of said activity.

Figure 4: Correlation between human population size and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (left), and between human population size and primary energy consumption (right) between 1850 and 2022. Source of data: Our World In Data for population (https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth), GHG emissions (https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions) and energy consumption (https://ourworldindata.org/energy).

Notes

* Let's not forget that we are just one of the countless life forms that inhabit the planet.

** While human activity generally tends to result in the alteration of the Earth's habitability and the destruction of living things, it should be remembered that many human beings throughout history, and even today, have not had this destructive relationship with their world.

References

[1] H. Ritchie et al., « Population Growth », Our World in Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth

[2] European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), « Urbanization: 95% Of The World’s Population Lives On 10% Of The Land », ScienceDaily, 2008. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/12/081217192745.htm

[3] Wikipédia, « Démographie de Paris ». https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=D%C3%A9mographie_de_Paris&oldid=223952282

[4] N. Elgrably, « Surpopulation: Elon Musk n’a pas tort », Le Journal de Montréal, 2022. https://www.journaldemontreal.com/2022/09/02/surpopulation--elon-musk-na-pas-tort

[5] H. Cuny, Le bon, la brute et le tyran - Ce que l’Anthropocène dit de nous. Maïa, 2023.

[6] A. M. Calafat, Z. Kuklenyik, J. A. Reidy, S. P. Caudill, J. S. Tully, et L. L. Needham, « Serum concentrations of 11 polyfluoroalkyl compounds in the US population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999- 2000 », Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 41, no 7, p. 2237‑2242, 2007. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17438769/

[7] R. Aubert et S. Horel, « Les PFAS, une famille de 10 000 « polluants éternels » qui contaminent toute l’humanité », Le Monde, 2025. https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2025/01/14/les-pfas-une-famille-de-10-000-polluants-eternels-qui-contaminent-toute-l-humanite_6496699_4355770.html

[8] United Nations, « Summary Progress Update 2021: SDG 6 — water and sanitation for all », UN-Water, 2021. https://www.unwater.org/publications/summary-progress-update-2021-sdg-6-water-and-sanitation-all

[9] World Health Organization, « Ambient (outdoor) air pollution », 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health

[10] P. J. Landrigan, « Air pollution and health », Lancet Public Health, vol. 2, no 1, p. e4‑e5, janv. 2017. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(16)30023-8/fulltext

[11] G. Ceballos, P. R. Ehrlich, et P. H. Raven, « Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction », Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2020. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1922686117

[12] WWF, « Living Planet Report − 2022: Building a nature-positive society. Gland, Suisse », WWF, Gland, Suisse, 2022. https://wwfint.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/embargo_13_10_2022_lpr_2022_full_report_single_page_1.pdf

[13] R. H. Cowie, P. Bouchet, et B. Fontaine, « The Sixth Mass Extinction: fact, fiction or speculation? », Biol. Rev., vol. 97, no 2, p. 640‑663, 2022, doi: 10.1111/brv.12816. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/brv.12816

[14] IPBES, « Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany », IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany, 2019. https://zenodo.org/record/3553579

[15] Wikipédia, « Jour du dépassement », Wikipédia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jour_du_d%C3%A9passement&oldid=222353690

[16] N. Fiala, « Measuring sustainability: Why the ecological footprint is bad economics and bad environmental science », Ecol. Econ., vol. 67, no 4, p. 519‑525, 2008. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921800908003376

[17] L214, « Dossier : les chiffres clés de la souffrance animale – Animaux abattus dans le monde », L214. https://www.l214.com/animaux/chiffres-cles/statistiques-nombre-animaux-abattus-monde-viande/

Conclusion

Human population growth has gone hand in hand with an increase in the occupation of the Earth's surface by our species to meet its various needs, above all in terms of food production, but also habitat, transport and the extraction of resources of all kinds.

It has also gone hand in hand with increased pollution of the Earth's surface, through the growing release of waste, whether greenhouse gases, eternal pollutants, plastics or microplastics.

The increase in the size of the human population is therefore concomitant with the increase in the alteration of the Earth's habitability, with more "non-human" living beings being exploited and exterminated, and an ever greater weight, both literally and figuratively, of our species on the living world.

These parallel developments lead naturally enough to a frequent question: isn't the major problem of our time overpopulation?

Not so fast! Because coincidence or correlation is no proof of causality. In the next article, we'll look at the respective responsibilities of different human populations in terms of their impact on the biosphere. Fundamentally different responsibilities, which beg the question: in the end, does the problem lie in the size of the population, or in the lifestyle of one part of the population? A question that begs another, just as disturbing: if we really had to reduce population size to reduce environmental impact, who would have to sacrifice themselves first?

Henri Cuny