Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

Anti-ecomodernism volume 1: Intensifying does not mean decoupling

Intensifying does not allow decoupling economic growth from environmental impact

According to Wikipedia, "ecomodernism is an environmental philosophy which argues that technological development can protect nature and improve human wellbeing through eco-economic decoupling, i.e., by separating economic growth from environmental impacts" [1]. Before getting to the heart of the matter, let's dwell for a moment on an important word that lies at the heart of ecomodernist thinking: decoupling. Two coupled processes evolve together, and decoupling them means dissociating their respective evolutions. Today, economic growth goes hand in hand with an increase in environmental impacts; there is a coupling between economic growth and environmental deterioration. Decoupling would mean that economic growth would take place without any additional deterioration, or even, on the contrary, with a rehabilitation of the natural environment.

Ecomodernism received a spotlight following the publication in 2015 by 18 “ecomodernists” of the text entitled "An Ecomodernist Manifesto" [2]. One of the central ideas of ecomodernism is that intensifying human activities makes it possible to decoupling human development from environmental alteration. The manifesto formulates this fundamental principle very early on:

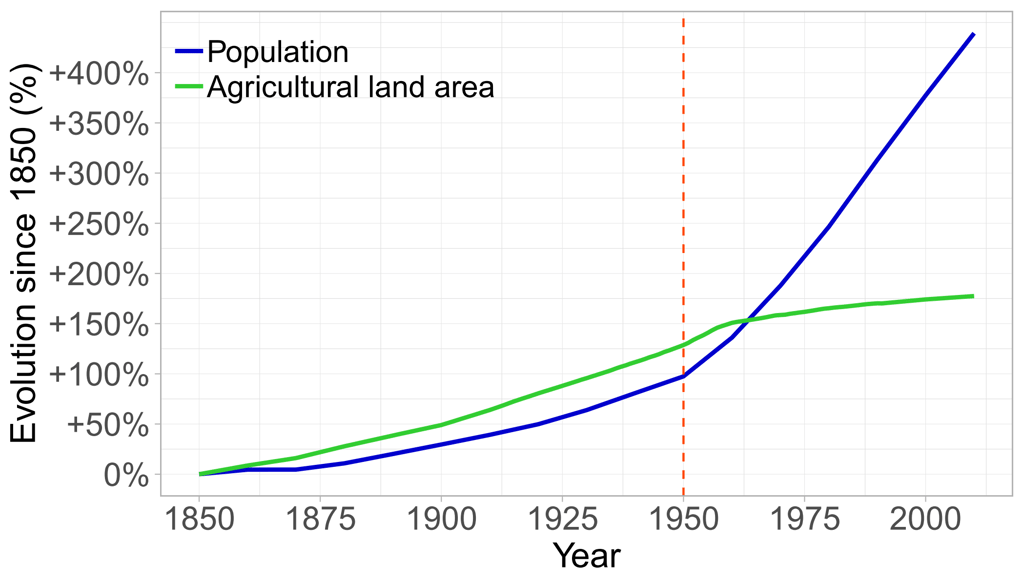

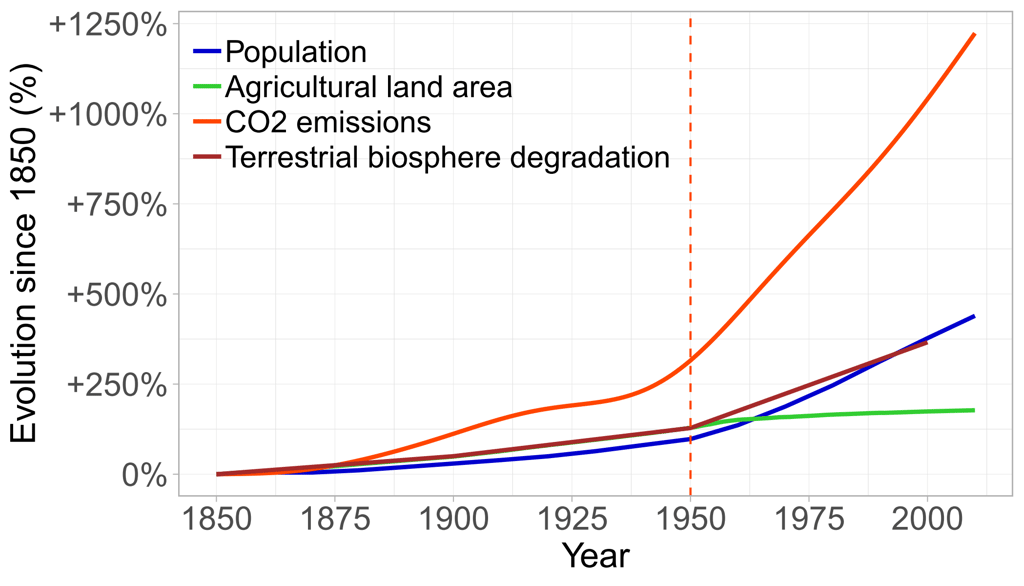

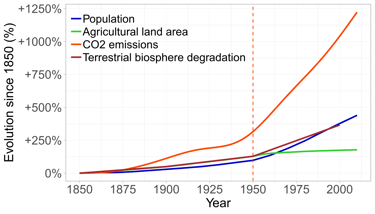

Figure 1: Relative evolution of human population and agricultural land area worldwide since 1850. From 1850 to 1950, population and agricultural land area increased in parallel. After 1950, the population explodes, while the agricultural land area increases only slightly. This relative decoupling is the result of intensification, which enables much more food to be produced on the same surface area. Is this the beginnings of an absolute decoupling between human development and environmental impact? Data source: IGBP [9].

“Intensifying many human activities — particularly farming, energy extraction, forestry, and settlement — so that they use less land and interfere less with the natural world is the key to decoupling human development from environmental impacts. These socioeconomic and technological processes are central to economic modernization and environmental protection. Together they allow people to mitigate climate change, to spare nature, and to alleviate global poverty.”

A poignant and hopeful message, worthy of a Miss France contestant's speech! They just failed to mention peace on Earth. I don't know about you, but when I read that, I thought that intensification was really a wonderful process. Unfortunately, carried away by my enthusiasm (and perhaps also by my eternal distrust), I tried to scrape off the varnish and realized that I'd been duped again by one of those damned misleading ads...

Intensifying allows limiting land use but not the overall impact of human activities: example of agriculture

Since intensification has been underway for several decades now, we already have some data to analyze its effects on the environment.

The idea that intensifying allows limiting environmental impact may seem understandable at first glance: if we limit the space occupied by a human activity (habitat, food production, energy production...), then we must limit the impact of this activity on the Earth's surface.

Unfortunately, this reasoning is extremely partial and simplistic, since it considers that a given activity only has an impact through the surface area it occupies on land. Thus, seeing environmental impact solely through the prism of land use is a major problem with ecomodernist reasoning. If we take a more global approach (i.e., considering all impacts, not just land use), the idea that intensifying can reduce our impact on the planet seems much less obvious.

To demonstrate this crucial point, let's take the example of agricultural intensification. Logically, intensifying agriculture reduces the area needed to produce a certain quantity of food. For example, the massive intensification of agriculture in the second half of the 20th century limited the increase in the world's agricultural land area, even though the period was marked by a population explosion. It should be noted, however, that there is no absolute decoupling between the size of the human population and agricultural land area: the increase in agricultural land area is less marked than that of the population, but both indicators continue to rise (the decoupling is relative).

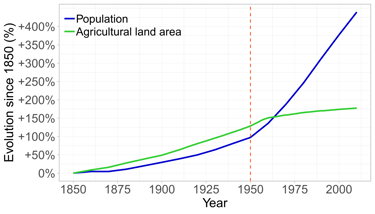

In some countries (France, for example), agricultural intensification has even contributed to a phenomenon of forest recolonization, following millennia of deforestation. There has been an absolute local decoupling between population growth and loss of forest cover. A phenomenon that the manifesto presents as proof of the great success of (technological) development and intensification in decoupling human activities from "wilderness".

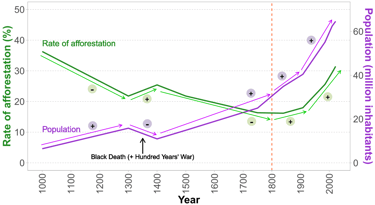

Figure 2: Trends in afforestation rate (ratio of forest area to total land area) and human population in France over the last millennium. Prior to the 19th century, there was a close relationship between demography and forest cover: as the human population increased, forest cover decreased, and vice versa. From the 19th century onwards, and even more so in the 20th century, agricultural intensification led to the recolonization of agricultural land with forest. As the population grew, so did the forest area. There is an absolute decoupling between population growth and loss of forest cover. Data sources: For the afforestation rate, data reconstructed from an article by Yves Birot for the period prior to 1840 [1] and the IGN memento for the period 1840-2022 [2]; For population, data from Our World in Data [3].

This point can already be widely criticized. In a globalized economy, a systemic approach is essential to understand the dynamics of ecosystems, which have also been globalized to some extent. The recolonization of forests in some countries is also due to the fact that these countries have relocated a large number of activities that consume space and resources, which in turn means relocating deforestation. In fact, some so-called "developing" countries (Brazil, Indonesia...) are clearing land on a massive scale to increase their agricultural area. This increase in farmland is aimed at meeting rising domestic consumption, as well as exporting to "developed" countries. In fact, at global level, there is still a terrible net loss of forest cover, even if this is less than at the end of the 20th century (around 5 million hectares of forest lost per year since 2000, compared with 8 million during the 1990s; [13]). There is therefore a local (i.e. geographically restricted) rather than global decoupling between human development and loss of forest cover.

Let's now broaden the scope of our analysis and assess the environmental impact of agricultural intensification on a more global scale. In concrete terms, agricultural intensification rests on two pillars: the mechanization of farming practices and the massive use of inputs. These two pillars are themselves dependent on fossil fuels, which provide the energy for machinery and the raw material for the synthesis of fertilizers and pesticides. The consequences are far-reaching: on the one hand, the combustion of fossil fuels by machines generates greenhouse gases (GHGs); on the other, the use of pesticides contributes to the destruction of living organisms [14, 15, 16], while the application of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers generates nitrous oxide [17, 18], a gas with a warming potential 300 times greater than that of CO2, and alters the nitrogen cycle.

In short, the intensification of agriculture has a massive contribution to climate change and the extinction of living organisms - the two most spectacular, tragic and global consequences of human activity! The recolonization of forests in certain countries therefore seems a meagre and pitiful consolation compared to the terrible environmental damage inherent in the intensification of agriculture. If we take the previous graph and add CO2 emissions and an indicator of biosphere degradation, it becomes clear that talking about decoupling makes little sense when the multiplicity of environmental impacts is taken into account.

Figure 3: Relative evolution of human population, agricultural land area, CO2 emissions and biosphere degradation worldwide since 1850. Unlike agricultural land area, CO2 emissions and biosphere degradation continue to evolve in parallel with human population after 1950. There is not a global decoupling between human development and environmental impacts during the 20th century, which was the time of the great intensifying of human activities. Data source: IGBP [9].

The 19th and 20th centuries have been the time of intensifying

While intensification is at the heart of ecomodernism, it is by no means a new idea - which ties in with the fact that ecomodernism is not modern, a criticism I will develop in a forthcoming article - and the last two centuries (especially the 20th) have been precisely a time of intensifying human activities.

Intensification of energy first, with the industrial exploitation of concentrated energy sources named fossil fuels (oil, gas, coal), in addition to the more diffuse sources that have been used for millennia (wind, sun, biomass...). Before 1850, fossil fuels were exploited little or not at all, and the main source of energy was biomass. In 1900, with just over 6,000 terawatt-hours (TWh), biomass already accounted for just 50% of the global energy mix (12,000 TWh), with fossil fuels (exclusively coal) accounting for the other half [3]. In 2022, with 180,000 TWh, global energy consumption have beeen 15 times greater than in 1900. Biomass's contribution to this total has fallen to 6%, despite absolute consumption almost doubling since 1900 (11,000 TWh), while fossil fuels' contribution has risen to 77%, with absolute consumption increasing 23-fold (137,000 TWh)!

Intensification of settlement too, with a spectacular phenomenon of urbanization: between 1800 and the present day, the proportion of the population living in cities has risen from 5% to 55% [4]. 2007 would be the tipping point at which more than half the world's population lives in a large city. Given that the global population has grown considerably over the same period, the urban population has exploded: between 1950 and 2018, it rose from 750 million to 4.2 billion [5].

Intensification of agriculture, with the mechanization of farming practices and the growing use of synthetic inputs (fertilizers and pesticides). Between 1961 and 2019, fertilizer consumption increased by a factor of 4 (from 52 million to 215 million tonnes per year) [6], while between 1990 and 2020, pesticide consumption rose by 60% (from 1.69 million to 2.66 million tonnes per year) [7]. Agricultural intensification has considerably increased yields, and equally considerably reducing the labor required to produce food. Before 1800, farmers were the majority (60-75%) of the working population in France. By 1980, they accounted for less than 10%, and by 2020, less than 2% [8]!

Some immoral aspects of intensification passed over in silence: example of intensive livestock farming

The ecomodernist manifesto places intensification at the heart of a strategy to preserve "wilderness", but is very scant on one of its aspects: animal husbandry (only aquaculture is mentioned as something desirable). The intensification of animal husbandry is a phenomenon that has already largely taken place in recent decades. In France, for example, 80% of the animals consumed today come from intensive livestock farming [19].

In line with ecomodernist ambitions, the intensification of livestock farming is being taken to extremes. In 2022, China inaugurated the world's largest pig concentration system: a 26-storey skyscraper housing 650,000 pigs in tiny automated stalls [20]. A first that is likely to be emulated, as other similar projects are said to be in the pipeline.

Figure 4: Giant pig farm in Ezhou, China. A 26-storey building in which hundreds of thousands of pigs spend a few months before slaughter. Is intensification the creation of hell on Earth for the sentient beings that inhabit the planet? Source: New York Times [20].

As with intensive crop production, intensive livestock farming reduces land use. However, here too, a more global view highlights the dramatic aspects of intensification in terms of environmental impact, and even more so in terms of respect for nature. For example, intensifying in no way reduces the contribution of livestock farming to the greenhouse effect, given that today, livestock is responsible for around 6% of annual global GHG emissions [21].

But it is above all on the ethical side that the intensification of livestock farming raises questions. “Traditional” livestock farming can already be judged harshly in many respects, but intensification takes ignominy a notch further. I won't go back over the (unspeakable) conditions inherent in intensive livestock farming, which have been described in detail here and there [22, 23, 24, 25], but I do wish to denounce the unbearable discrepancy between our treatment of animals and recent scientific findings.

At a time when ever more surprising discoveries are being made about the emotionality, sensitivity, intelligence (and what we might call consciousness) of animals [26, 27], this model of animal husbandry seems like an anachronism. Does leaving a little space for "wild nature" (a supposedly ardent wish of ecomodernists who present themselves as "out of deep love and emotional connection to the natural world") justify the implementation of abject systems for billions of sentient living beings? I don't know if this is the modern paradise promoted by ecomodernists, but for animals, this paradise has the appearance of hell and is the result of a process called "intensification".

Maybe I'm going to throw a stone in the pond, but I don't think it's completely crazy to push this line of reasoning for plants. In fact, scientific knowledge is beginning to change the way we perceive plants, and may even call into question the traditional animal/plant dichotomy. Thus, there is a growing tendency to recognize sensitivity and intelligence in plants [28]. Is the intensification of plant cultivation ethical in the light of these new concepts? We are probably not mature enough to address this question, but it does not seem totally improbable that it will come up sooner or later.

I'm not saying that the way forward is to no longer kill animals or plants for our benefit; life is such that some living beings have to die so that others can continue to live. But what we do know about life (i.e. what we are rediscovering scientifically, but which some humans have known since the dawn of time through other forms of knowledge acquired through experience and shared through tradition) invites us to show respect, humility and compassion for non-human living beings. A respect, humility and compassion that intensification shamelessly flouts.

Intensification remains a recent phenomenon because it depends on abundant, cheap energy

To fully understand the implications of intensifying human activities, it's crucial to understand what this process is all about. Intensifying is not simply a matter of "doing more in less space", but first and foremost of concentrating energy and matter, a concentration which itself requires the expenditure of energy. If, for example, you wish to intensify the decomposition of dead leaves in your garden, you must first gather them into a pile rather than leave them scattered on the ground, and this concentration of matter requires the expenditure of energy.

So, even if intensification has been around for a few decades and is therefore nothing new, it remains a recent phenomenon, because it depends on abundant, cheap energy, in this case from fossil resources. Oil, gas and coal are the bedrock of intensification. As we have seen in agriculture, intensification depends on fossil fuels to power the countless machines that have replaced humans and animals in various tasks, and to synthesize the fertilizers and pesticides on which this agricultural model is based.

The same logic (i.e. the dependence of intensification on high energy availability) is at work for urbanization. Before developing this example a little further, let's take a moment to read what the manifesto claims about it:

“Cities occupy just 1 to 3 percent of the Earth’s surface and yet are home to nearly four billion people. As such, cities both drive and symbolize the decoupling of humanity from nature, performing far better than rural economies in providing efficiently for material needs while reducing environmental impacts.”

Once again, the reasoning is totally partial, if not idiotic, since it only considers the surface area occupied on the ground as having an impact on the environment. Besides, if cities are so much more efficient than rural economies at meeting material needs, why have humans essentially lived outside urbanized environments for 99% of our species' history? Were our ancestors too stupid to understand that they had to concentrate on small areas to achieve opulence? Why has urbanization only taken off in the last few decades?

The answer is simple: urbanization, like intensive agriculture, is a recent phenomenon, because it involves concentrating matter and energy, and is therefore dependent on abundant, cheap energy, in this case from fossil fuels. Firstly, urban infrastructures are extremely costly in terms of resources and energy: building a skyscraper several hundred meters high requires the concentration of large quantities of materials (and therefore a great deal of energy to ensure the flow of materials) as well as large quantities of energy for the construction itself. Secondly, as the urban environment produces very few essential goods, it requires large flows of materials to ensure its day-to-day operation.

Admittedly, urbanization concentrates the population in "small areas" (in a country like France, the urban environment occupies almost a quarter of the territory and continues to expand rapidly [29]), but to claim that it reduces environmental impacts is particularly questionable when we consider the full diversity of these impacts [30].

Intensification in the service of the great cult of growth in production-consumption

If intensification in no way reduces the overall impact of human activity on the Earth's surface, that was never its intention in the first place. Indeed, intensification is first and foremost intended to serve the great cult of our civilization: growth as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), i.e. the rise in the human population and the consumption of each individual.

Since the 19th century, growth in production and consumption has been the Holy Grail of our societies, and everything must be done to achieve it. The pursuit of this ultimate goal is necessarily accompanied by an increase in the consumption of energy and materials. In this context, the intensification of various human activities appears essential. In a previous article, I illustrated this by taking the emblematic example of palm oil, a hyper-intensive system aimed at meeting a growing demand for oil that would be very complicated to satisfy with more conventional systems (olive, sunflower, rapeseed...) with much lower yields.

Intensification, which enables us to produce more per unit of space, can be seen as the counterpart of productivity gains, which enable us to produce more per unit of time. Combined, intensification and productivity gains ultimately enable us to produce more, and are thus two crucial parameters on which to play to achieve the objective of growth in production and consumption.

The consequences of the intensification and productivity gains at work since the 19th century, and even more so since 1950, are summarized in the planetary dashboard (or Anthropocene dashboard) and can be summed up in one expression: the "Great Acceleration". In other words, a phase marked by a sharp rise in numerous socio-economic (population, GDP, life expectancy, quantities of resources used, energy used...) and Earth system (GHG content of the atmosphere, ocean acidification, degradation of living organisms...) trends. In short, a phase of coupling between human development and the alteration of planetary sustainability.

A problem of purpose rather than means

So, we can always say that to make intensification "green", it's enough to replace polluting energies with "non-polluting energies", or to develop GHG capture and storage systems. This "coulda, shoulda, woulda" logic is, moreover, blithely repeated in the manifesto, which repeatedly refers to "modern energies" that are apparently formidable, but which we don't really know what they are.

Above all, the problem is infinitely broader and more complex than the mere question of energy sources and their drawbacks. For example, nuclear energy (frequently put forward as a miracle solution, even though it currently accounts for less than 5% of energy used [3]!), will be of no help in producing the fertilizers and pesticides on which intensive agriculture depends.

In the same way, using "clean energy" to power the hyper-intensive livestock farms we set up will do nothing to change the abject and, in my view, immoral treatment inflicted on the countless living beings who pay the price. Living beings who, I would remind you, come from the same process as we do: that of life, or nature, the very thing that eco-modernists claim to cherish while supporting a process that leads to its mistreatment.

Ultimately, the problem has much more to do with what we do with energy than with the inherent disadvantages of each energy source. In this sense, Aurélien Barrau hypothesizes that the discovery of a clean, unlimited source of energy (the dream of many of our contemporaries) would be the worst-case scenario for the future of life on Earth, as we would then have no limits to our destructive action [31].

More generally, the example of energy shows that the problem lies first and foremost in the finality of our activity (the growth in production and consumption) rather than in the means (intensification, extensification, productivity gain, the search for "clean energy"...) used to achieve it. An aim that is in no way called into question by the ecomodernist project, which continues to make growth the Holy Grail of our age, even going so far as to postulate the absence of limits to growth. In my view, this postulate - which I will address in a separate article - is at least as erroneous as the idea that intensification would make it possible to decouple human development and the alteration of the Earth's habitability.

References

[1] « Ecomodernism », Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecomodernism

[2] J. Asafu-Adjaye, L. Blomqvist, S. Brand, B. Brook, R. Defries, et E. Ellis, « An ecomodernist manifesto », 2015. http://www.ecomodernism.org/manifesto-english

[3] H. Ritchie, M. Roser, et P. Rosado, « Energy », Our World in Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/energy

[4] H. Ritchie et M. Roser, « Urbanization », Our World in Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization

[5] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, « World Urbanization Prospects 2018: Highlights », 2019. https://population.un.org/wup/publications/Files/WUP2018-Highlights.pdf

[6] H. Ritchie, M. Roser, et P. Rosado, « Fertilizers », Our World Data, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/fertilizers

[7] H. Ritchie, M. Roser, et P. Rosado, « Pesticides », Our World Data, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/pesticides

[8] O. Chardon, Y. Jauneau, et J. Vidalenc, « Les agriculteurs : de moins en moins nombreux et de plus en plus d’hommes », Insee., 2020. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/4806717

[9] IGBP, « Planetary dashboard shows “Great Acceleration” in human activity since 1950 », 2015. http://www.igbp.net/news/pressreleases/pressreleases/planetarydashboardshowsgreataccelerationinhumanactivitysince1950.5.950c2fa1495db7081eb42.html

[10] Y. Birot, « Les forêts et les hommes : quelles co-évolutions ? », in La Forêt et le Bois en France en 100 questions, 2015. https://www.academie-foret-bois.fr/chapitres/chapitre-1/fiche-1-05/

[11] IGN, « Mémento, édition 2023 », 2023. https://inventaire-forestier.ign.fr/IMG/pdf/memento_2023.pdf

[12] H. Ritchie et al., « Population Growth », 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth

[13] FAO, « Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main report. Rome, Italy », 2020. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca8753en

[14] S. Seibold et al., « Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers », Nature, vol. 574, no 7780, Art. no 7780, 2019. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1684-3

[15] F. Geiger et al., « Persistent negative effects of pesticides on biodiversity and biological control potential on European farmland », Basic Appl. Ecol., vol. 11, no 2, p. 97‑105, 2010. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1439179109001388

[16] M. A. Tsiafouli et al., « Intensive agriculture reduces soil biodiversity across Europe », Glob. Change Biol., vol. 21, no 2, p. 973‑985, 2015. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/gcb.12752

[17] K. A. Smith, I. P. McTaggart, et H. Tsuruta, « Emissions of N2O and NO associated with nitrogen fertilization in intensive agriculture, and the potential for mitigation », Soil Use Manag., vol. 13, no s4, p. 296‑304, 1997. https://bsssjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-2743.1997.tb00601.x

[18] H. Tian et al., « A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks », Nature, vol. 586, no 7828, Art. no 7828, 2020. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2780-0

[19] S. Finger, « Porcs, bovins, volailles, la vraie vie de la viande française dans l’élevage intensif », Libération, 2018. https://www.liberation.fr/france/2018/06/04/porcs-bovins-volailles-la-vraie-vie-de-la-viande-francaise-dans-l-elevage-intensif_1656528

[20] D. Wakabayashi et C. Fu, « China’s Bid to Improve Food Production? Giant Towers of Pigs. », The New York Times, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/08/business/china-pork-farms.html

[21] H. Ritchie, M. Roser, et P. Rosado, « CO₂ and Greenhouse Gas Emissions », Our World in Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-greenhouse-gas-emissions

[22] M. Ricard, Plaidoyer pour l’altruisme: la force de la bienveillance. Nil, 2013.

[23] Y. N. Harari, Sapiens: Une brève histoire de l’humanité. Albin Michel, 2015.

[24] J. Henriques, « Une vie de cochon », Mediapart, 2016. https://blogs.mediapart.fr/edition/droits-des-animaux/article/100416/une-vie-de-cochon

[25] L214, « La viande, un concentré de souffrance ». https://www.viande.info/elevage-viande-animaux

[26] F. De Waal, Sommes-nous trop « bêtes » pour comprendre l’intelligence des animaux ? Les Liens qui libèrent, 2016.

[27] P. Le Neindre, M. Dunier, R. Larrère, et P. Prunet, La conscience des animaux. Quæ, 2018.

[28] S. Mancuso, R. Temperini, et A. Viola, L’intelligence des plantes. Albin Michel, 2013.

[29] F. Clanché et O. Rascol, « Le découpage en unités urbaines de 2010 », Insee Prem., vol. 1364, p. 1‑4, 2011. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1280970

[30] J.-C. Bontron, « L’empreinte énergétique des modèles d’urbanisation et d’habitat », Pour, vol. 218, no 2, p. 71‑79, 2013. https://www.cairn.info/revue-pour-2013-2-page-71.htm

[31] Une énergie infinie et propre, serait le pire scénario -Aurélien Barrau. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xDAojbi688I

[32] A. Balmford et al., « The environmental costs and benefits of high-yield farming », Nat. Sustain., vol. 1, no 9, Art. no 9, 2018. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-018-0138-5

Conclusion

To sum up: intensifying human activities has been underway for around two centuries, and particularly since the end of the Second World War. It is part of a global process of production-consumption growth, which has led us to the "great acceleration", a phase marked by the abrupt evolution of many socio-economic trends (population, GDP, resources consumed, energy used, life expectancy, infant mortality...), but also of many Earth system trends (GHG levels in the atmosphere, ocean acidification, collapse of non-human life...).

Intensifying has certainly limited the increase in land use on the Earth's surface, but it has also had catastrophic global consequences for the biosphere, contributing decisively to the 6th mass extinction of life on Earth and sudden climate change. Despite this calamitous record, it is this process that eco-modernists propose to pursue in order to reconcile human activity with the preservation of "wild nature".

Don't put words in my mouth: if we remain stuck in our current "development" model, extensification would probably do no better than intensification in terms of environmental impact - or even worse in some respects, according to some studies [32]. Moreover, the purpose of this article is not to oppose intensification and extensification, but to reject the idea that intensifying is a way to decoupling human development from environmental impacts. The decoupling enabled by intensification, if it exists, is only partial (it only concerns certain aspects of environmental alteration, such as the loss of forest area) and relative (for example, the loss of forest area has slowed down, but the forest continues to decline), whereas we need total and absolute decoupling.

Ultimately, the problem is not so much in the way (intensification vs. extensification, energy sources used, etc.) of carrying out human activities as in the very nature of these activities (artificializing soils, spreading poisons and waste, exploiting living beings…) and, even more, their purpose: to produce and consume ever more. A purpose which is driven by the fantasy of achieving happiness through material consumption, as well as by the myth of the possibility of infinite growth. A myth which is in no way questioned, on the contrary constituting another central pillar of ecomodernism, and which I will tackle in the next article.

Henri Cuny