Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

Anti-ecomodernism volume 2: No, the limits to growth are not theoretical

Anyone who believes in infinite growth is either a madman, an economist, or an ecomodernist

We saw in a previous article that ecomodernist thinking is based on a first mistaken assumption, namely that the intensification of human activities would decouple human development from environmental impacts. In this article, we'll see that this (major) error of reasoning is not the only one, by tackling a second postulate at the heart of ecomodernist thinking, which appears at least as questionable: that limits to growth are theoretical and irrelevant to human activity.

Before getting to the heart of the matter, let's take a second to clarify the terms. The proponents of this cult of material accumulation (i.e., increased production and consumption) may have taken a run at words like growth, development or progress, but their conception of these processes is nonetheless fundamentally limited and materialistic. For example, when it comes to growth, we're obviously not talking about growth in the beauty of the world, in life, in peace, in interactions between humans or with non-humans, but about pure human (hyper)expansionism, which wants humanity to consume ever more energy and resources to produce and consume ever more goods and services. Growth in production-consumption, however, leads to numerous declines, the most terrible of which is that of our planet's habitability.

The myth of infinite growth in production-consumption lies at the heart of ecomodernist thinking

The ecomodernist manifesto [1] forcefully reaffirms the ideal of "progress" or "development" (funny words to describe a phenomenon that alters planetary habitability, that is) through the growth of production-consumption, highlighting the (real) changes in human prosperity (increased life expectancy, lower infant mortality, fewer famines...) that have taken place over the last two centuries.

With the fervent wish to pursue this trajectory, the ecomodernist manifesto goes so far as to cast doubt on the existence of limits to the growth of production and consumption, claiming that material and energy resources are unlimited:

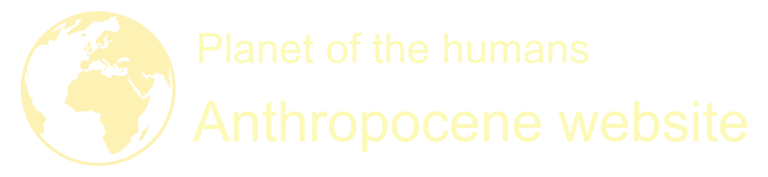

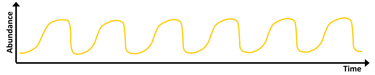

Figure 1: Dynamics of a bacterial population grown in a petri dish. Source: modified from a figure published on Infogreen [2].

“Despite frequent assertions starting in the 1970s of fundamental "limits to growth", there is still remarkably little evidence that human population and economic expansion will outstrip the capacity to grow food or procure critical material resources in the foreseeable future. To the degree to which there are fixed physical boundaries to human consumption, they are so theoretical as to be functionally irrelevant. The amount of solar radiation that hits the Earth, for instance, is ultimately finite but represents no meaningful constraint upon human endeavors. […]. With proper management, humans are at no risk of lacking sufficient agricultural land for food. Given plentiful land and unlimited energy, substitutes for other material inputs to human well-being can easily be found if those inputs become scarce or expensive.”

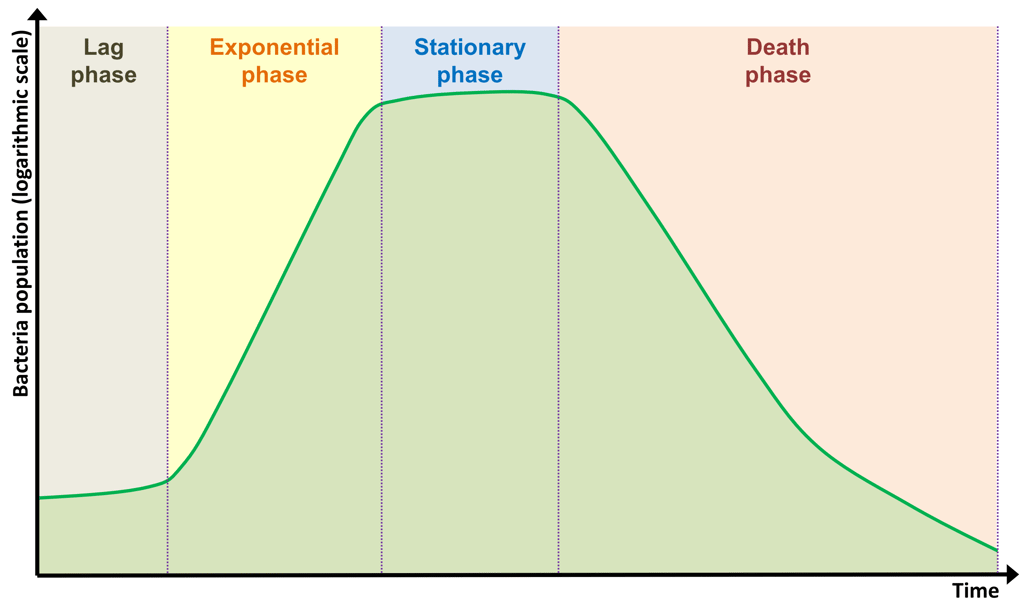

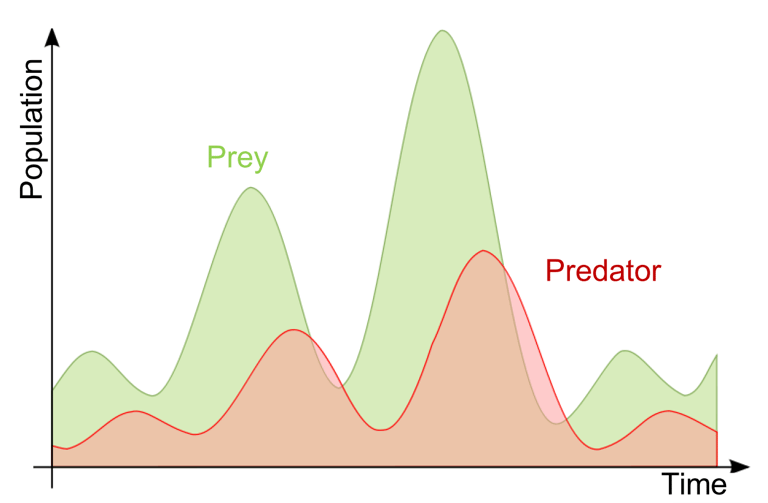

Figure 2: Theoretical long-term dynamics of a population of microorganisms in their natural environment. Source: modified from a figure published in Fink & Manhart, Current Opinion in Systems Biology, 2023 [3].

Beyond this theoretical dynamic, research has demonstrated the extraordinary ability of microorganisms to adapt their growth to changing environments [4, 5], particularly when nutrients become scarcer. This adaptability to environmental conditions is achieved through various strategies, such as the formation of biofilms, the production of an extracellular matrix or the "pausing" of the organism. Just like humans, microorganisms have incredible abilities to adapt to variations in their environment.

Nevertheless, the limits to growth are patent in the growth of microorganisms. In fact, limits to growth appear obvious and absolutely necessary when we consider the rate at which microorganisms multiply. In the absence of limits, a bacterium like Escherichia coli could continue to grow exponentially and reach a population the size of the Earth in two days [5, 6]! In other words, there wouldn't be much space left for the others, and the limits wouldn't be those of available resources, but of the space that could be occupied.

What about macro-organisms? Well, as with microorganisms, the study of population dynamics highlights the existence of limits to growth, rather than the possibility of unlimited growth. All living beings, particularly in order to feed themselves, take resources from their environment. Among "non-humans", the balance between resource extraction and replenishment is generally balanced. And in the event of an imbalance, it cannot persist for very long.

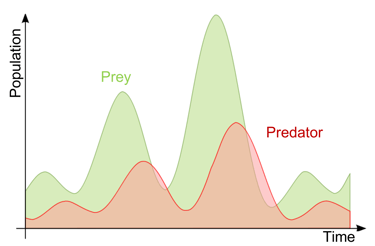

Predator-prey relationships bear witness to this limitation. If, in a given environment, predators eat almost all their prey, they can no longer feed. Their population declines and the prey can then multiply, after which the predator population can also increase again. So, despite short-term fluctuations in populations, the predator-prey balance remains balanced over the longer term. What's more, in natural environments, it is estimated that only one predator attack in ten is successful. This means that, even in the event of an attack, the prey retains a high chance of survival, which also contributes to the predator-prey balance.

Figure 3: Theoretical predator-prey dynamics. When the number of prey increases, the number of predators can increase. If predators exert too much pressure on the prey population, the latter eventually decreases, which in turn leads to a decrease in the number of predators. At present, humanity is in the midst of a steep rise in the predator curve, but prey have already largely begun to fall. In nature, the fall of the predator curve usually follows that of the prey... Source : Wikipedia (https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:LotkaVolterra_en.svg).

According to this vision, there is theoretically no limit to the consumption of energy and resources, opening the door to unlimited growth in the human population or in the consumption of each individual. Now let's see what science has to say about the theoretical nature or otherwise of limits to growth. To do this, we'll turn to population dynamics, a branch of ecology that looks at the evolution of numbers within populations of living beings as a function of environmental influences.

What does science have to say about the limits to growth?

If you've ever done microbiology, you may have grown bacteria in a petri dish. The game consists in placing bacteria in a shallow, transparent cylindrical container (a petri dish, that is), along with a gel containing the nutrients they need. In such a well-resourced environment, with an ideal temperature (37°C), bacterial population dynamics generally follow a typical pattern, shown in the following figure:

Several phases can be distinguished:

An initial lag phase, during which the bacteria adapt to their new environment without multiplying.

An exponential phase, which describes a population that is growing... exponentially (the population doubles over a given period of time, every hour for example); there are no limits to growth (for a while!), and the birth rate is much higher than the death rate.

A stationary phase, during which the population levels off due to one or more environmental limitations (resource depletion, accumulation of waste, etc.); birth and death rates may remain close for some time, for example until resources are renewed (in which case growth may resume if it was indeed resource availability that was limiting), or until conditions become more severely limited (in which case we enter the decline phase).

A death phase, during which the population decreases, as the mortality rate exceeds the birth rate due to the worsening of the environmental limitation(s).

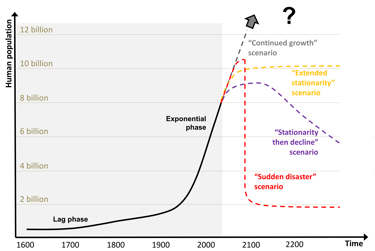

Perhaps in the midst of an exponential growth phase, lost in the immensity of its petri dish, euphorized by the great availability of resources and the exponential multiplication of its species, a bacterium (an ecomodernist one?) assumes the absence of limits to growth? However, science is clear: in a petri dish, growth is limited, and this bacterium, like its congeners, will experience this sooner or later.

Population dynamics have also been studied for microorganisms in their natural environment. It shows a theoretical pattern, with alternating rises and falls in populations as a function of fluctuating resource availability [3].

Are there material and energy limits to human activity?

Biology proves beyond doubt that for the living beings that inhabit the Earth, population growth is limited. However, the most fervent defenders of economic growth, like all fanatics, are of the stubborn type. They'll probably retort that humanity isn't in a petri dish, or that with our exceptional technologies we're capable of freeing ourselves from the laws of nature. So, yes, there are limits to the growth of bacteria, trees, antelopes or billions of other living organisms, but are there really limits to human expansionism?

I admit it: mankind is not a simple culture in a petri dish, nor even a living being dependent on the predation of a few species. Homo sapiens is an ubiquitous predator. Unlike fox, for example, we don't just prey on hares, field mice or voles, but on all living creatures and even on a large part of the mineral world. Human's prey is not a restricted group of plants or animals; it's the whole Earth (and now even the solar system for the most radical proponents of growth [7]).

As we saw in the previous section, biology teaches us that unlimited growth is purely theoretical, whereas the limits to growth are clearly demonstrated by experience. Biological phenomena that grow ad infinitum simply don't exist in nature. To claim, contrary to scientific fact, that the limits to growth are theoretical would therefore appear to be daring, to say the least, even for human systems. On the basis of scientific knowledge, particularly of the dynamics of living populations in their environment, it is hard to believe that the dynamics begun a few decades ago can be sustained for much longer.

In theory, resources and energy may seem limitless. It's true, the quantities of matter and energy at play in the universe are ridiculously large compared to human needs. A well-known example (taken up by the manifesto) is that in just over an hour, the Earth receives from the sun a quantity of energy equivalent to what human activity uses every year [8]. True, but there's a fundamental difference between the potential (the burning theory) and the available (the real thing).

To be available, energy must be captured, stored if possible and transported. If we take the example of the sun, the limiting factor is certainly not the quantity of energy received at the Earth's surface, but rather the capacity to effectively use this energy, which involves its capture, possible storage and distribution. Plants are infinitely better at this than humans. A tree, for example, captures solar energy through photosynthesis, stores it in its organism (notably in its wood) and then distributes it fairly so that other living beings can benefit from it (through leaf fall, dead wood, etc.).

Evolution being what it is, we humans are less able than plants to use solar energy, and have to deal with this "handicap". To use energy other than that which we ingest, we can't rely on our bodies alone, so we have to build systems to capture or generate (solar panels, wind turbines, hydroelectric dams, oil and gas wells, coal mines, nuclear reactors...) energy, store it (batteries, supercapacitors...) and distribute it (electricity grid, gas pipelines, oil pipelines...). These systems are costly (in resources, energy, space, work time, etc.) and cannot be installed everywhere.

In reality, available resources and energy are limited. In fact, humanity has lived for hundreds of thousands of years in an environment with potentially unlimited resources and energy, but with a "subsistence economy" (an expression which condescendingly suggests that our ancestors merely survived) fully adapted to the resources and energy actually available (and therefore limited).

What changed that? What made limits that seemed so obvious suddenly become so remote that we come to believe they don't exist? The revolution came with the discovery of extraordinarily concentrated sources of energy: fossil fuels. These radically changed the game, turning every human being into a potential Iron Man [9]. The upheavals in the organization and functioning of human systems have been so brutal and multiple that they have given us a feeling of invulnerability.

Like the bacteria in its petri dish (yes, that's an image), some people may well have become intoxicated by the exponential growth phase we've been experiencing over the last few decades, which is the result of the material and energy profusion derived from fossil fuels. The power these resources have given us, and the upheavals they have caused, may have led us to believe that anything was possible for the future, and that there were indeed no limits, or that these were so remote as to be irrelevant.

Yet fossil fuels are also finite, as we consume more and more of them, and are therefore increasingly dependent on them. In 1950, oil, gas and coal accounted for around 70% of global energy consumption (i.e. just over 20,000 TWh out of almost 29,000 TWh) [10]. In 2022, they will account for almost 80% of a global consumption that has in the meantime multiplied by 6 (i.e. around 137,000 TWh out of almost 180,000 TWh). In 2022, nuclear power accounted for less than 5% (6,700 TWh) of global energy consumption, while solar and wind power together accounted for around 5% (9,000 TWh). These energy sources do not replace fossil fuels, but rather supplement them to meet growing demand.

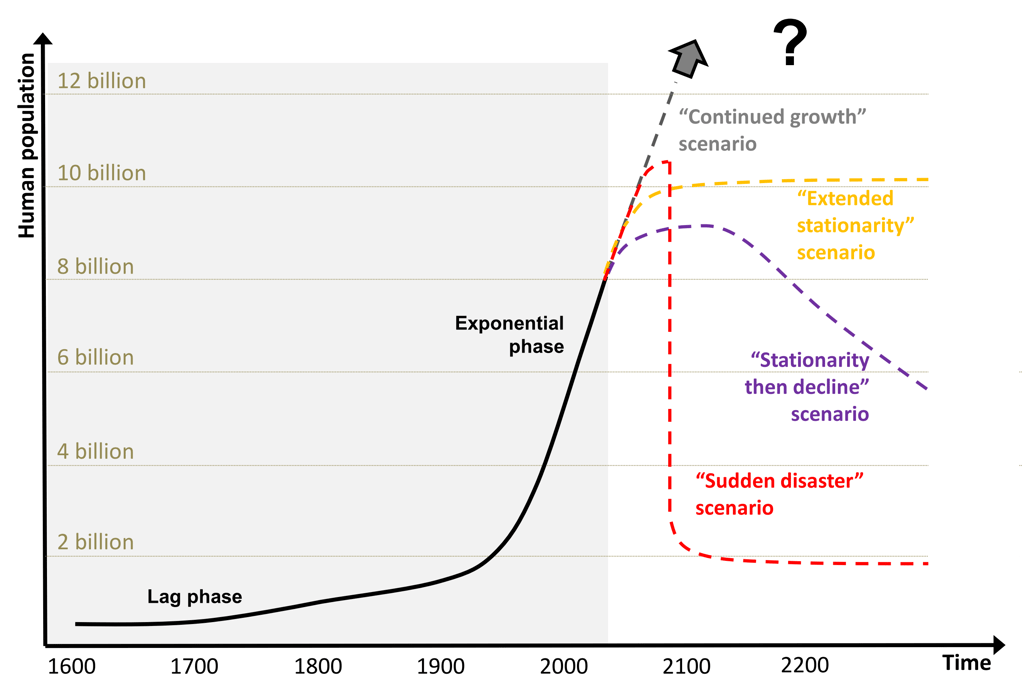

By analogy with the dynamics of a bacterial population in a petri dish, we can assume that after a very long lag phase, humanity has been in the midst of an exponential growth phase for several decades now. This growth follows the addition of abundant resources to the environment, in this case fossil fuels. What will happen when the availability of these fossil resources stagnates or diminishes? Hardly anyone can say, but it's clear that continued growth in the human population seems hardly credible, let alone economic growth as measured by GDP.

Figure 4: Observed global human population dynamics since 1600 (solid black line) and "wet-finger" projections for the future (dashed colored lines). After a very long lag phase, the human population has been growing exponentially for several decades now, in line with the addition of abundant resources to the environment: fossil fuels. What kind of future? An infinite number of scenarios are possible, but given the finiteness of fossil resources, scenarios of continued growth seem hard to envisage.

Other limits to human expansionism?

Fossil fuels have made us all-powerful, but they are finite. What's more, their use has potentially devastating side-effects that can also constitute a serious limit to some people's expansionist ambitions. There is, of course, the question of GHG emissions and induced climate change, but the general fact is that we are using the omnipotence conferred by fossil resources to alter planetary habitability.

As we have seen in the case of bacteria, resource availability is not the only limiting factor, and the deterioration of the environment may well put an end to growth and even lead to death phase. If we continue on our present course, it is quite possible that the deterioration in the conditions of our very existence will eventually reach a threshold beyond which human decline will be inevitable.

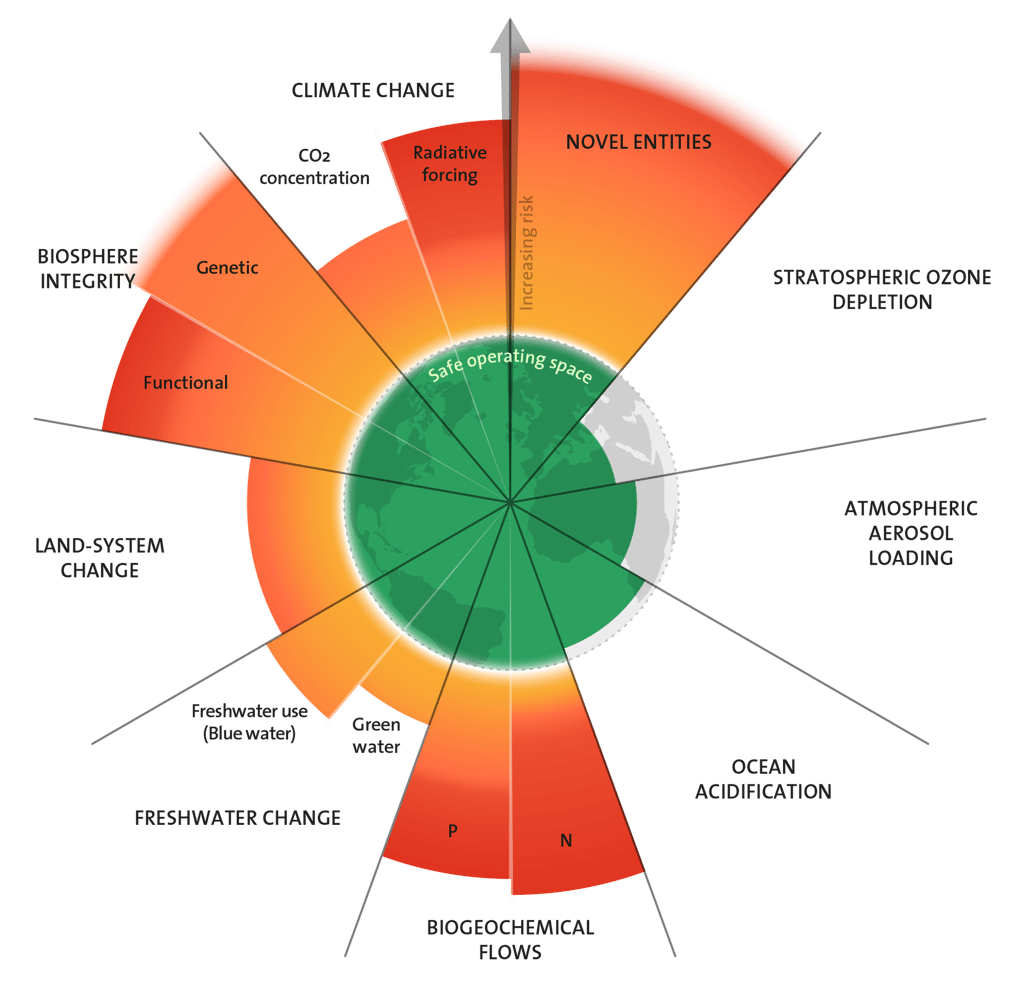

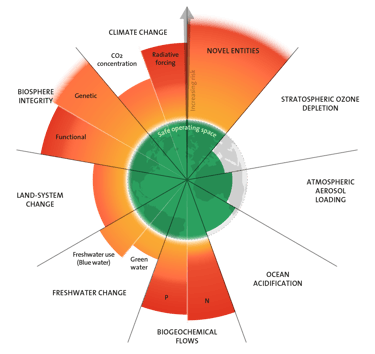

It's an amusing coincidence that ecomodernism postulates the absence of limits to growth at a time when science is conceptualizing planetary boundaries [11]. Nine processes fundamental to the functioning of the Earth system, each of which is clearly modified by human action, form the conceptual framework for planetary boundaries. For six of these nine processes, scientific assessment shows that recent trajectories have already taken us outside the safety zone (i.e. that the planetary limit has been exceeded). This overstepping of limits poses growing risks to the development of human societies and ecosystems [11].

Figure 5: The 9 planetary boundaries defined by the Stockholm Resilience Centre. 6 limits have already been exceeded, increasing the risks to the development of human societies and ecosystems. Sources: Stockolm Resilience Centre (https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html).

Similarly, the planetary dashboard (or Anthropocene dashboard) reveals the astonishing growth (the "Great Acceleration") of many Earth system trends over recent decades (atmospheric GHG concentration, ocean acidification, biosphere degradation...), suggesting that these dynamics cannot be sustained for much longer without serious consequences for humans and all life on Earth [12].

Any more limits?

The preceding sections have shown that there are at least two fundamental limits to human expansionism: the availability of resources (with the crucial difference between theoretical, potentially unlimited resources, and actually available, inherently limited resources) and environmental deterioration (assessed in the Anthropocene dashboard or by planetary boundaries). These two limits suggest that postulating the absence of physical limits to growth is particularly theoretical, if not dangerously irrational.

These two major limits are ecological limits, i.e. they are linked to the physical laws that govern the functioning of terrestrial ecosystems. They correspond to the physical boundaries that ecomodernists assume to be theoretical and irrelevant. There are, however, other limits to growth. I won't elaborate on them here, as they are less directly linked to the physical limits to which ecomodernists refer, but it is worth mentioning them to understand that growth remains a process fundamentally constrained by multiple limits.

Timothée Parrique, for example, adds social and political limits to the growth of production-consumption to ecological limits [13]. The social limits are linked to what Timothée Parrique calls "the sphere of reproduction" (as opposed to the "sphere of production" as evaluated by GDP), i.e. a set of conditions (rest, family, unpaid work...) necessary to maintain production. The sphere of reproduction is not infinitely extensible (on the contrary, it tends to be reduced by the growth of the sphere of production), which constitutes a limit to the extension of the sphere of production.

The political limits are more to do with inequalities and the fact that continued growth in production-consumption is no guarantee of individual well-being and happiness. Easterlin's famous paradox, for example, states that beyond a certain threshold, continued growth in per capita income or GDP does not mechanically translate into increased individual happiness. We can add that prolonged growth does not necessarily translate into greater satisfaction of individual needs. Today, growth in production translates into increased inequality, with the bulk of production captured by a handful of humans with inordinate power.

These limits are in line with the philosophical debate surrounding growth, which, beyond a certain level of production-consumption, may well be seen as a process that is no longer desirable. Clearly, growth could (should!) only be seen as a transitory means of improving material conditions for human life, and not as an end in itself to be pursued ad vitam aeternam.

Today, economic production is more than sufficient to meet people's needs. The fact that some people do not even have enough to live on is essentially due to a problem in the allocation of economic production, and not to the volume of production itself. Rather than producing more (which, as the increase in inequality shows, does not enable those with little to have more, but rather those who already have a lot to have even more), we could very well choose to produce less and distribute more equitably. We could finally achieve a stationary economy (or a post-growth economy) that would ensure that the needs of the greatest number are met, while taking ecological limits into account. A choice that would require an in-depth revision (let say a revolution) of our social organization, rather than the development of technological means to produce more. Of course, this possibility is not discussed by ecomodernists, who see growth as it has been thought for the past two centuries, as an ultimate goal to be pursued at all costs.

In addition to ecological, social and political limits, we can also add another form of limit that is far too little discussed for my taste (a consequence of anthropocentrism and the sanctification of the human): human limits, which I developed in my book "Le bon, la brute et le tyran - Ce que l'Anthropocène dit de nous" [14]. Yes, human is a brilliant being, but his intelligence is no less limited. In this respect, a particularly interesting theory is that which contrasts the slow evolutionary dynamics of our biology with the rapid evolutionary dynamics imposed by modern technologies [15].

On the one hand, our biology evolves very slowly. For example, our anatomy and brain have evolved very little over thousands of years [16]. We would therefore be very similar to our distant ancestors, and some of our behavioral traits have been selected for the hunter-gatherer lifestyle that has prevailed for over 95% of our history. On the other hand, over the last few centuries and even more so over the last few decades, our technological environment has undergone considerable developments, and these are accelerating. In short, our biology is not evolving at the same pace as technology.

The consequence of this "desynchronization" between biology and technology is that we are not at all equipped to cope with certain aspects of the modern world that are precisely linked to technology. This "handicap" manifests itself in a number of defective ways of thinking, including the well-known cognitive biases - falsely logical thinking mechanisms, mostly unconscious, that lead to a systematic distortion in the processing of information. Quite simply, we are riddled with cognitive biases, dozens of which have been identified [17]. These biases can have serious consequences, not least in our (in)ability to respond to the crises we have created [15]. It would therefore be healthy to recognize our own limitations, which constitute a major limit to human hyper-expansionism.

References

[1] J. Asafu-Adjaye, L. Blomqvist, S. Brand, B. Brook, R. Defries, et E. Ellis, « Un manifeste éco-moderniste », 2015. http://www.ecomodernism.org/francais

[2] Infogreen, « La boîte de Petri et la population mondiale », Infogreen, 2022. https://www.infogreen.lu/la-boite-de-petri-et-la-population-mondiale.html

[3] J. W. Fink et M. Manhart, « How do microbes grow in nature? The role of population dynamics in microbial ecology and evolution », Curr. Opin. Syst. Biol., vol. 36, p. 100470, 2023. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2452310023000276

[4] J. W. Fink, N. A. Held, et M. Manhart, « Microbial population dynamics decouple growth response from environmental nutrient concentration », Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 120, no 2, p. e2207295120, 2023. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2207295120

[5] M. Bergkessel, D. W. Basta, et D. K. Newman, « The physiology of growth arrest: uniting molecular and environmental microbiology », Nat. Rev. Microbiol., vol. 14, no 9, p. 549‑562, 2016. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrmicro.2016.107

[6] « Population dynamics », Nat. Rev. Microbiol., vol. 14, no 9, p. 543, 2016. https://www.nature.com/articles/nrmicro.2016.123

[7] A. Piquard, « Jeff Bezos rêve d’envoyer l’humanité dans l’espace », Le Monde, 2021. https://www.lemonde.fr/economie/article/2021/06/11/jeff-bezos-reve-d-envoyer-l-humanite-dans-l-espace_6083678_3234.html

[8] « Quel est le potentiel énergétique de l’énergie solaire ? », Futura Sciences. https://www.futura-sciences.com/planete/questions-reponses/energie-renouvelable-potentiel-energetique-energie-solaire-999/

[9] J.-M. Jancovici et C. Blain, Le Monde sans fin, miracle énergétique et dérive climatique, Dargaud. 2019.

[10] H. Ritchie, M. Roser, et P. Rosado, « Energy », Our World in Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/energy

[11] W. Steffen et al., « Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet », Science, vol. 347, no 6223, p. 1259855, 2015. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1259855

[12] W. Steffen, W. Broadgate, L. Deutsch, O. Gaffney, et C. Ludwig, « The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration », Anthr. Rev., vol. 2, no 1, p. 81‑98, 2015. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2053019614564785

[13] T. Parrique, Ralentir ou périr - L’économie de la décroissance, Seuil, 2022.

[14] H. Cuny, Le bon, la brute et le tyran - Ce que l’Anthropocène dit de nous. Maïa, 2023.

[15] S. Bohler, Le bug humain, Robert Laffont, 2019.

[16] S. Neubauer, J.-J. Hublin, et P. Gunz, « The evolution of modern human brain shape », Sci. Adv., vol. 4, no 1, p. eaao5961, 2018. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aao5961

[17] « Biais cognitif », Wikipédia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Biais_cognitif&oldid=213053318

Conclusion

Biology has repeatedly demonstrated the existence of limits to the growth of living beings, whether in experimental conditions or in natural environments. Living beings compete or cooperate to live in a constrained environment, particularly with regard to limited resources.

In fact, physical limits to growth appear to be a welcome law of nature, since they allow the expression of life in all its diversity, rather than the infinite growth of a single life form that would end up taking up all the space.

Driven by fossil fuels, which have considerably increased the potential for resource extraction and processing, humans have succeeded in pushing back, at least for a time, the limits to human growth. However, this "abnormal" extension of the human sphere is totally dependent on resources (fossils, in other words) that are themselves limited, and has led to imbalances that pose growing threats to the continued development of human societies, and even to their very existence.

Certainly, the continual supply of additional resources (from the solar system? the galaxy?) and the elimination of any waste (in space?) offers the potential to push the limits to growth even further. But beyond flaming theory there are the facts, and these unambiguously show that unlimited growth is infinitely more theoretical than the existence of limits to growth. Consequently, considering that there are limits to growth and taking these limits into account in one's development project - in other words, adopting an anti-ecomodernist attitude - seems far more serious and sensible than the opposite.

Henri Cuny