Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

The history of the human population and the demographic singularity of the Anthropocene

From 1 billion people in 1805 to 8 billion in 2022!

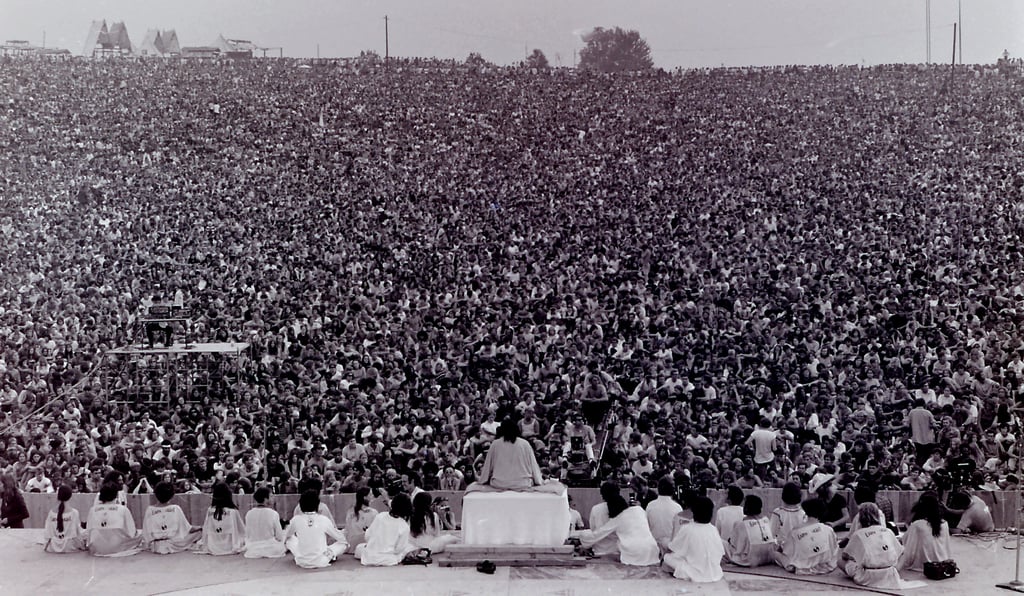

Swami Satchidananda on stage in front of a huge crowd as he opens the Woodstock Festival in 1969. Image source: Mark Goff, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3f/Swami_opening.jpg).

Our species has been around for about 300,000 years [1]. In October 2022, global population passed a new symbolic threshold, with the census of over 8 billion Homo sapiens* human inhabitants on Earth. This news barely raised an eyebrow for most of us. It has to be said that we were busy counting the Covid19 dead, who are indeed numerous in absolute terms, but who nevertheless make up only a tiny fraction of the world's population.

There are billions of us, and so it seems to have become a matter of course for most of us, as if it had always been so. Yet, as we shall see, far from being normal, the current population and its recent dynamics are hardly believable singularities when set against the long-term history of our species. With over 8 billion of us, this is quite simply an extraordinary anomaly, in the truest sense of the word. Let's try to explain why.

The long-term history of Homo sapiens population size and the singularity of the Anthropocene

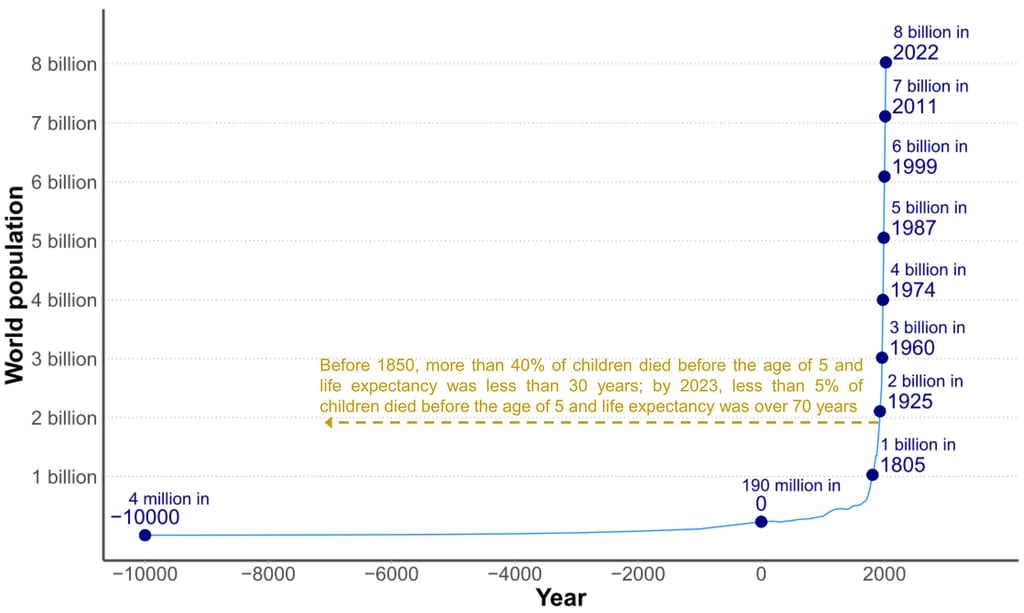

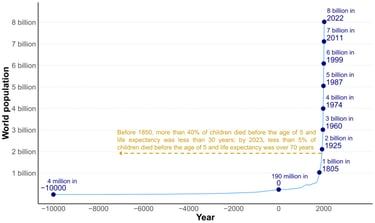

Let's start by taking a step back from the present situation and looking at human population dynamics over the long term (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Evolution of the human population (Homo sapiens) over the last 100,000 years. Data source: Our World in Data (https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth#explore-data-on-population-growth) [2].

There are several lessons to be learned from this graph:

There have never been as many humans on Earth as there are today.

Before 1800, there was a general long-term trend towards a gradual increase in population (albeit with possible transient phases of decline, not visible on the graph as they were overwhelmed by the scale), which nevertheless remained between a few thousand and a few million individuals for hundreds of thousands of years.

Over the past few decades, however, the world's population has risen extremely sharply.

Whereas it took almost 300,000 years to reach a population of 1 billion Homo sapiens, in just over 200 years the population has risen from 1 billion (in 1805) to 8 billion (in 2022).

Deadly events such as the First World War (followed by the Spanish flu) or the Second World War are not detectable on the graph, such is the power of the growth dynamic. There's no point in looking for an episode like Covid19, since it's only an epiphenomenon in terms of overall population dynamics.

It is possible to go back even further in time, although ancient estimates of world population are naturally fraught with considerable uncertainty. It is estimated that 100,000 years ago, there were between 100,000 and 300,000 Homo sapiens individuals on Earth [3].

Some have put forward the idea that our species passed through a "population bottleneck" around 70,000 years ago with the Toba catastrophe**, with only a few thousand individuals remaining [4]. Subsequent studies, however, have tended to invalidate this hypothesis [3, 5].

Whatever, the long-term dynamics reveal a general trend towards population growth, from a few tens to a few hundreds of thousands of individuals over 50,000 years ago, to 4 million individuals 12,000 years ago, and around 200 million individuals in the year 0. It is clear, however, that these figures and dynamics are out of all proportion to what has been happening over the last few decades: viewed over the long term, the recent period simply appears to be a sudden anomaly! It is the demographic singularity of the Anthropocene.

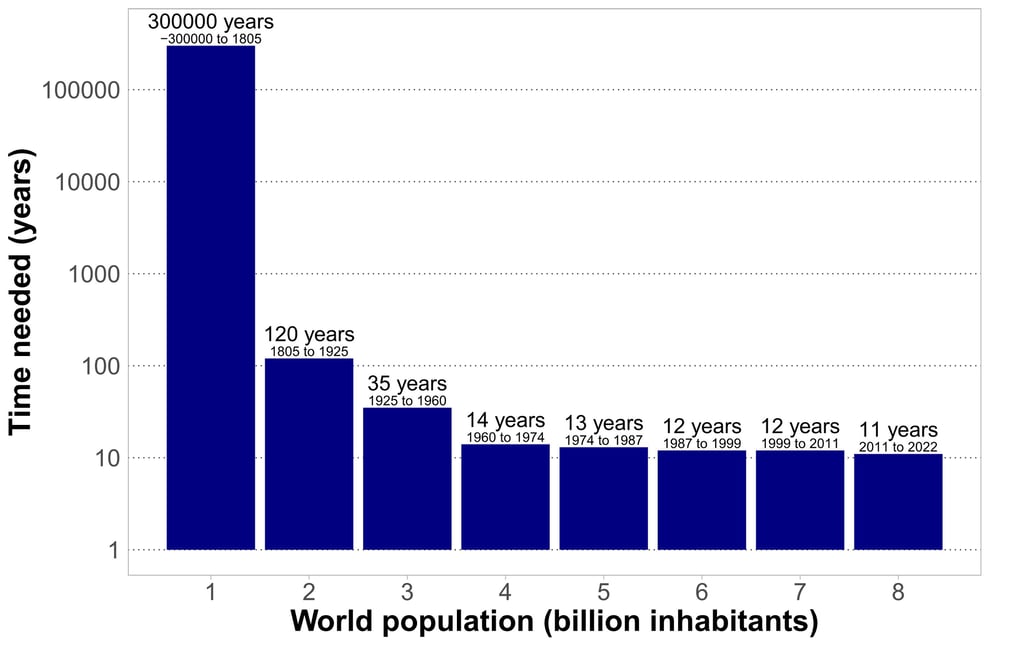

Another way of understanding the singularity of recent dynamics is to look at the time it took to reach each additional billion inhabitants (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Time needed to reach each additional billion inhabitants in the world population. Note that the ordinate scale is not linear, but logarithmic. Data source: Our World in Data (https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth#explore-data-on-population-growth) [2].

We had to wait until the very beginning of the 19th century - some 300,000 years if we consider the date of appearance of our species [1] - to reach the first billion Homo sapiens humans on Earth (confirming the billionaires' adage that the first billion is always the hardest). After that, times shortened incredibly: it took 120 years to reach the 2nd billion, 35 years for the 3rd and less than 15 years for each successive billion!

Finally, the time needed to double the population is worth considering. Whereas it took 262 years for the population to double from 0.5 billion (1543) to 1 billion (1805), it took 120 years to go from 1 to 2 billion (1805-1925), 49 years to go from 2 to 4 billion (1925-1974) and 48 years to go from 4 to 8 billion (1974-2022).

This sudden rise in population is explained in particular by a sharp increase in life expectancy, as well as by a considerable drop in infant mortality. Before 1800, humans lived on average less than 30 years, and over 40% of children died before the age of 5 [6, 7] - figures that seem unthinkable and intolerable today! In 2024, life expectancy has exceeded 73 years, and less than 5% of children die before the age of 5 [6, 7]!

As I'm not a specialist, I won't dwell here on the underlying causes of these spectacular changes. The era is certainly marked by impressive medical progress and a meteoric rise in agricultural yields, but these developments themselves depend on numerous factors, so that it remains difficult to disentangle the precise causalities.

Nevertheless, it's fair to say that the wide availability of energy from fossil fuels is a crucial factor. By enabling the mechanization of many tasks and the production of immense quantities of agricultural inputs, it has provided the caloric intake that underpins population growth and given many of us the opportunity to devote time to tasks other than food production (medical research, personal care, etc.).

A singularity that begins at different times in different parts of the world

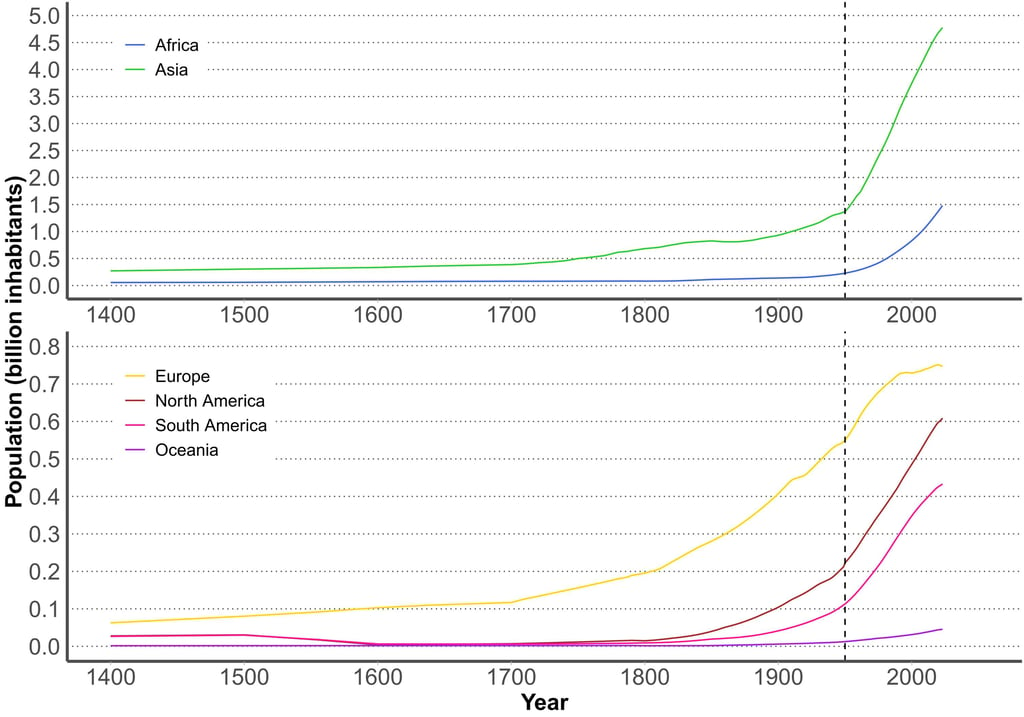

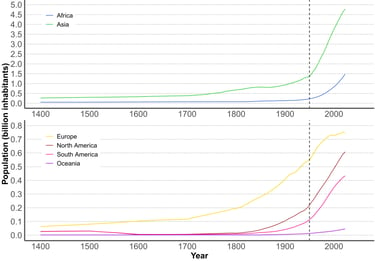

Observation of population dynamics over the last few centuries by continent shows that the Anthropocene demographic singularity did not begin at the same time in space (Figure 3).

It was in Europe, from the 18th century onwards, that brutal population growth first became apparent. By contrast, in Asia, and even more so in Africa, the singularity appears later, only appearing from the middle of the 20th century and the start of the Great Acceleration. It is indeed the dynamics of these two continents that are driving current global dynamics, since they contain almost 80% of the world's population and are the fastest-growing.

To illustrate this time lag, we can look at population trends over two successive hundred-year periods (1820-1920 and 1920-2020). Between 1820 and 1920, the population multiplied by 2 in Europe, by 1.4 in Asia and by 1.8 in Africa. Between 1920 and 2020, it multiplied by 1.6 in Europe, 4.4 in Asia and 9.2 in Africa!

America presents an intermediate situation, with strong population growth from the 19th century onwards, after a terrible decline in the 16th century following colonization***.

Figure 3: Human population trends by continent over the past 600 years. Data source: Our World in Data (https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth#explore-data-on-population-growth) [2].

Towards slower population growth, or even "negative growth"****...

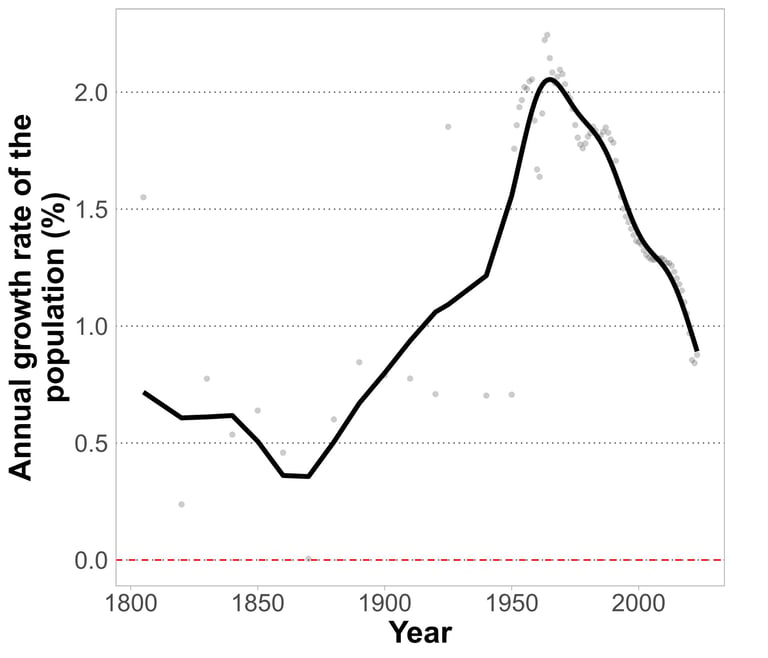

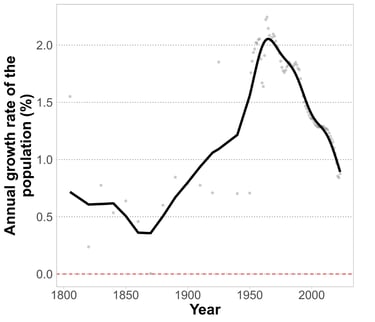

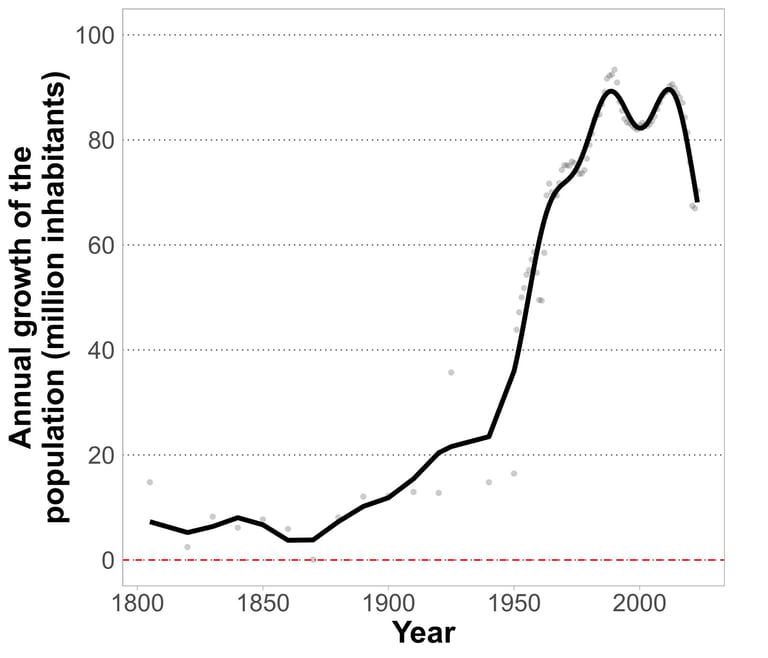

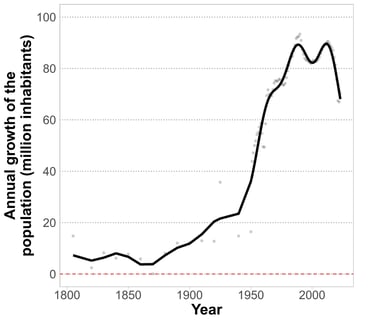

Even if this is still barely visible on the overall curve (Figure 1), the signs are that the incredible population growth of recent decades has reached a turning point and is tending to slow down. The annual rate of population growth (annual increase in the world's population relative to its size) has plummeted worldwide in recent years (Figure 4). Whereas in the 1960s-1970s, the annual population increase was around 2%, today it is less than 1%.

It has to be said, however, that while the rate is being reduced, it is being applied to an ever-larger population, so that in absolute terms growth remains very strong: in recent years, the population has grown by around 70 million a year, a figure equivalent to that seen in the 1960s and 1970s, when the rate of population growth was at its highest (but the population was smaller).

This annual rate corresponds to around 192,000 extra inhabitants per day, or 8,000 extra inhabitants per hour, or just over 130 extra inhabitants per minute. In the 5 minutes you spend reading this article, the Earth will be populated by around 650 extra people. 192,000 inhabitants per day is the equivalent of the world population of 12,000 years ago (4 million inhabitants), which is added every 21 days or so.

While growth remains strong, there are clear signs of a change in dynamics, with a decline in annual growth and a collapse in the annual population growth rate. This is due in particular to a sharp drop in the birth rate in certain regions of the world (partly offset by longer life expectancy, which is leading to an ageing population) [8], accompanied by a spectacular decline in male fertility [9].

The current global fertility rate is 2.25 children per woman, down from 3.31 in 1990 [8]. The fertility rate remains high in some regions (4.3 children per woman in sub-Saharan Africa, 2.7 in North Africa and Western Asia), but more than half of the world's countries and regions (France, USA, Japan, Russia... ) are below the replacement level of 2.1 live births per woman (i.e., the rate required to maintain the population at its current level), with rates even below 1.4 children per woman in some countries (China, Italy, Republic of Korea, Spain...) (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Trends in annual growth rate (annual increase in population relative to its size) and annual growth in world population since 1800. For each graph, the points correspond to the annual values in the data; the line shows the general trend (smoothed by generalized additive models). Data source: Our World in Data (https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth#explore-data-on-population-growth) [2].

Figure 5: World map of fertility rates (number of children per woman) by country in 2024. In most of the world's countries, the fertility rate is already below the threshold required to maintain the population (2.1 children per woman). Figure source: Wikipedia. Korakys, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Total_Fertility_Rate_Map_by_Country.svg.

Could this lead to a "demographic winter" (or demographic crash), as some people seem to worry [10, 11, 12, 13]?

... to a demographic winter?

The problem with billionaires is that they can't get enough: despite the unprecedented rise in population described above, which suddenly brought the population to an unprecedented level of over 8 billion people, some fear that the falling birth rate, particularly high in certain countries, could simply lead to the extinction of humanity, no less [14, 15]!

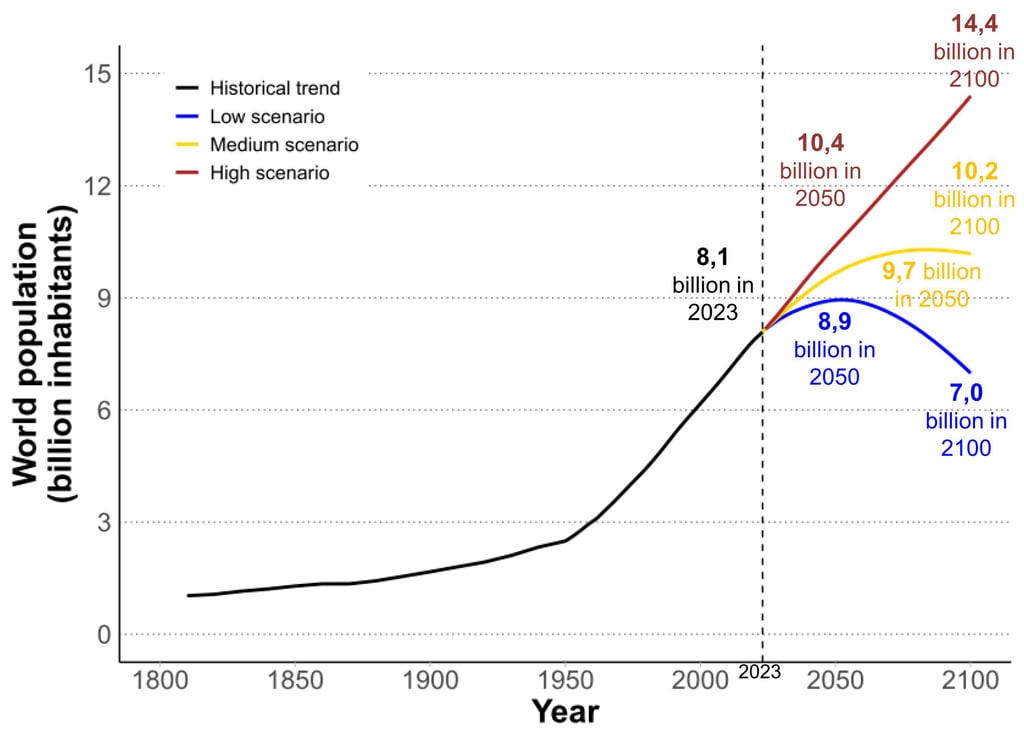

What's really going on? Do demographic forecasts predict the extinction of our species? Projecting the future population is, of course, a delicate exercise, given the unpredictable nature of the future, but the UN is an authority on the subject, and carries out projections according to a large number of scenarios, covering a wide range of possibilities [16].

The graph below (Figure 6) represents historical population trends and the UN's projected trends according to 3 scenarios, with the "medium" scenario generally being the most widely adopted:

The results suggest that it is highly likely that the human population will pass its peak in the course of the 21st century. Whatever the scenario, the population will continue to grow between now and 2050. In 2100, the "medium" scenario projects a high plateau at around 10 billion, while the "high" scenario simulates a continuous increase to over 14 billion! The "low" scenario is the only one to forecast a significant drop in population, which would fall to 7 billion, a figure that remains incredibly high relative to the human population over the long term.

So yes, our species is having fewer and fewer children. But let's reassure those worried about demographics: humanity isn't going to die out because of a decline in population growth, or even a decrease. While the falling birth rate in some countries is problematic from the point of view of the way our system works, based as it is on the foolish and futile ambition of perpetual growth, the extinction of non-human life that is occurring in parallel with the explosion of human life, climate change, the development of ever more deadly weapons and geopolitical tensions are placing humanity at infinitely greater risk, and should be a source of far greater concern to any rational mind.

Figure 6: Historical trend in world population since 1800 and UN projections to 2100 based on three scenarios. Data source : UN World Population Prospects 2024 (https://population.un.org/wpp/) [16].

Notes

* As is generally the case, I'll use shorthand like “population size” or “number of inhabitants” to refer specifically to the population of Homo sapiens humans, but it's worth remembering that the latter are just one of the countless life forms inhabiting the planet, and that, even if we've forgotten it, the Homo sapiens species has long coexisted with other species of humans on Earth.

** An extraordinary explosive eruption of the Toba volcano in Indonesia that is thought to have occurred 73,000 years ago and lasted 2 weeks, causing a volcanic winter that lasted 6 to 10 years, followed by a global cooling that lasted around a millennium.

*** The (re)discovery of America resulted in one of the most terrible hecatombes in human history, and probably the worst in terms of world population size. The conquistadors wiped out entire peoples and pushed the Amerindians to the brink of extinction, mainly by bringing with them a host of diseases to which they had no immunity, but also by despoiling, enslaving, persecuting and massacring them. In 1492, the Amerindian population may have reached 60 million; a century later, it had dwindled to just 4 million [17]. This means that colonization caused the disappearance of over 90% of the Amerindian population, or 10% of the world's population.

References

[1] J.-J. Hublin et al., « New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens », Nature, vol. 546, no 7657, p. 289‑292, 2017. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature22336

[2] H. Ritchie et al., « Population Growth », Our World in Data. 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth

[3] P. Sjödin, A. E. Sjöstrand, M. Jakobsson, et M. G. B. Blum, « Resequencing Data Provide No Evidence for a Human Bottleneck in Africa during the Penultimate Glacial Period », Mol. Biol. Evol., vol. 29, no 7, p. 1851‑1860, 2012. https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/29/7/1851/1070885

[4] S. H. Ambrose, « Late Pleistocene human population bottlenecks, volcanic winter, and differentiation of modern humans », J. Hum. Evol., vol. 34, no 6, p. 623‑651, 1998. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047248498902196

[5] J. Hawks, K. Hunley, S.-H. Lee, et M. Wolpoff, « Population Bottlenecks and Pleistocene Human Evolution », Mol. Biol. Evol., vol. 17, no 1, p. 2‑22, 2000. https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/17/1/2/975516

[6] S. Dattani, L. Rodés-Guirao, H. Ritchie, E. Ortiz-Ospina, et M. Roser, « Life Expectancy », Our World Data. 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy

[7] S. Dattani, F. Spooner, H. Ritchie, et M. Roser, « Child and Infant Mortality », Our World Data. 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality

[8] M. Roser, « Fertility Rate », Our World Data. 2014. https://ourworldindata.org/fertility-rate

[9] H. Levine et al., « Temporal trends in sperm count: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of samples collected globally in the 20th and 21st centuries », Hum. Reprod. Update, vol. 29, no 2, p. 157‑176, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36377604/

[10] L. Ferry, « Dénatalité, pourquoi c’est grave» », Le Figaro. 2025. https://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/societe/luc-ferry-denatalite-pourquoi-c-est-grave-20250103

[11] N. Silbert, « La France rattrapée par l’hiver démographique », Les Echos. 2024. https://www.lesechos.fr/economie-france/conjoncture/la-france-rattrapee-par-lhiver-demographique-2131637

[12] R. Legendre, « Hiver démographique : cette crise dont personne ne parle », l’Opinion. 2022. https://www.lopinion.fr/economie/hiver-demographique-cette-crise-dont-personne-ne-parle

[13] France Culture, « L’Italie face à son hiver démographique », France Culture. 2024. https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/le-grand-reportage/l-italie-face-a-son-hiver-demographique-8651860

[14] Le Parisien, « La fantasque milliardaire Elon Musk dit souhaiter à la planète "plus de bébés et de pétrole" » - Le Parisien. 2022. https://www.leparisien.fr/high-tech/la-fantasque-milliardaire-elon-musk-dit-souhaiter-a-la-planete-plus-de-bebes-et-de-petrole-29-08-2022-BS3GHSNYXRB7XAEJFBNHLJUO3U.php

[15] C. Hessoun, « Elon Musk avertit plusieurs pays d’une catastrophe à venir », La Nouvelle Tribune. 2024. https://lanouvelletribune.info/2024/12/elon-musk-avertit-plusieurs-pays-dune-catastrophe-a-venir/

[16] United Nations, « World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2024/TR/NO. 9. New York: United Nations. », 2024. https://population.un.org/wpp/publications

[17] A. Koch, C. Brierley, M. M. Maslin, et S. L. Lewis, « Earth system impacts of the European arrival and Great Dying in the Americas after 1492 », Quat. Sci. Rev., vol. 207, p. 13‑36, 2019. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277379118307261

Conclusion

The history of the Homo sapiens human population, which dates back some 300,000 years, is that of a long and gradual increase, which took place over tens of thousands of years before the sudden and unbelievable growth observed over the last few decades. This sudden and unprecedented increase led to the Earth being populated by over 8 billion people, whereas the population of previous millennia had never exceeded a few thousand to a few hundred million inhabitants.

This demographic singularity of the Anthropocene naturally raises questions about the future of the human population. The meteoric growth of recent decades is coming to an end, with a slowdown in global growth and even a decline in population in certain regions of the world. This dynamic can be explained by a significant drop in the fertility rate, which has already fallen below the threshold ensuring population renewal in most countries.

Is there reason to fear a “demographic winter” leading to the extinction of the human species? There's no risk of that: the number of humans is such that, even if a significant drop in fertility may lead to a reduction in the population, it will nevertheless remain for a long time at a level unseen for hundreds of thousands of years.

In addition to the development of armaments, the danger comes from the alteration of the environment and the biological annihilation of non-humans, which are taking place in a disturbingly parallel way to the hyper-expansion of the human life form. What makes you think that population growth and a certain “overpopulation”, and not a falling birth rate or an eventual decline in the human population, constitute a major danger of the Anthropocene? We'll address this delicate question in the next article.

Henri Cuny