Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

What future for the Anthropocene? - Scenario 1: The Great Decoupling

Unlimited growth of production-consumption within reach?

The Anthropocene naturally calls for an exploration of our past, in an attempt to understand the path (causes and temporality of the Anthropocene, which I have discussed here, for example) that has brought us to this point.

It is also an invitation to question ourselves about our future: in view of the many indicators increasing dramatically (number of humans, consumption of resources, greenhouse gas emissions, etc.), the observation of the extinction of life or the extremely brutal climate changes underway, the following questions naturally arise: what will become of the Earth's surface? Of humanity? Of each of us and our descendants?

I propose to address these questions in a 4-part article. Each of the first 3 parts will present a clear-cut scenario for the possible future evolution of the Anthropocene, while the fourth will offer a brief synthesis. In this first part, we'll focus on the scenario on which thermo-industrial civilization is betting everything: that of the Great Decoupling.

What is the Great Decoupling?

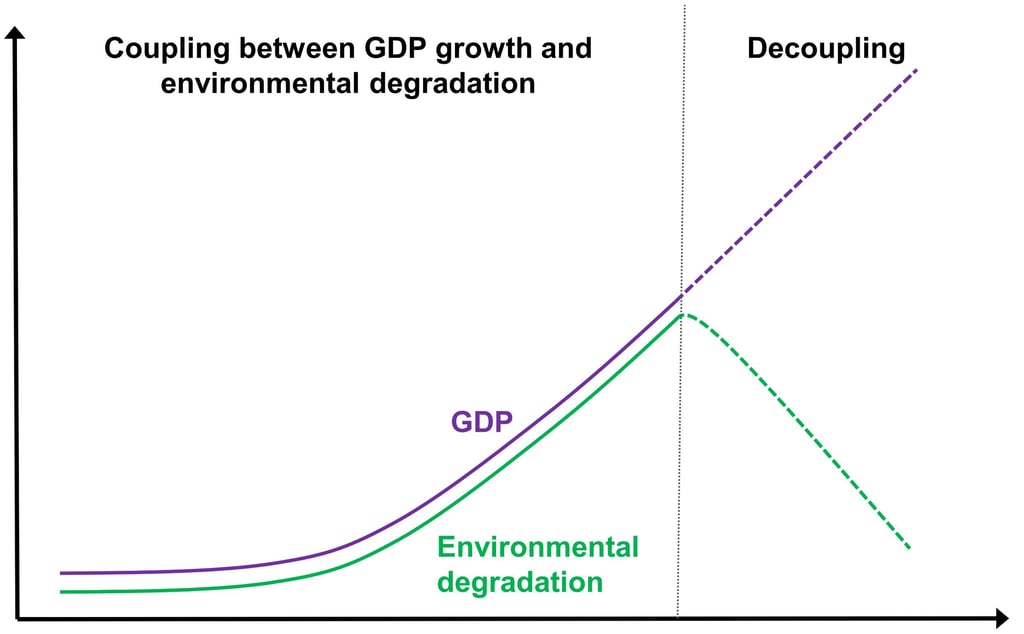

Until now, there has been a very strong correlation between human development, as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and the destruction of the environment: the corollary of an increase in GDP is an increase in the alteration of the Earth's surface, as the dashboard of the Anthropocene [1] clearly shows.

The Great Decoupling is the idea that progress (well, GDP growth, which isn't the same thing, but is nonetheless the indicator of progress for thermo-industrial civilization) could in future be achieved without harming the Earth's habitability.

Figure 1: Illustration of the Great Decoupling concept. Until now, GDP growth has been closely linked (i.e. coupled) to the alteration of terrestrial habitability. The idea of the great decoupling is to continue GDP growth, but without damaging terrestrial habitability. The key to decoupling lies in technology and innovation. The great decoupling is synonymous with green growth, ecological transition or sustainable development.

The "magic wand" for decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation is to be found in the deities of the modern age, namely the goddesses of "technology" and "innovation". Thanks to them, we're going to invent new ways of producing and consuming that will be infinitely more resource-efficient (energy, materials, space...) and less polluting, paving the way for unlimited growth in production-consumption. The road to happiness, I tell you!

The great decoupling is in fact the new name for a fairly old concept, but one which, like a snake, changes its skin when the previous one becomes worn: we have thus spoken for a time of green growth, sustainable development or ecological transition, but all of this is in fact one and the same thing and is based on the idea of GDP growth decoupled from the alteration of the Earth's surface.

By designing an all-powerful technology that opens the way to "piloting the Earth system" and unlimited growth, the great decoupling can also be assimilated to climate engineering, technological fix, ecomodernism or cornucopianism.

The scenario on which thermo-industrial civilization has chosen to all-in

Since the Great Decoupling requires no serious questioning (GDP growth, science, technology and innovation as the path to prosperity and happiness for all), it is a particularly popular scenario. In a previous three-part article (part 1, part 2 and part 3), I vilified ecomodernism, a movement on the rise that makes the Great Decoupling an ultimate goal, seeing GDP growth as humanity's salvation and technological development as the fundamental solution to the man-made ecological mega-crisis.

Radical eco-modernists like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are firm believers in the Great Decoupling and are trying to convert the masses to it. Then there's French President Emmanuel Macron or Minister Bruno Le Maire and many others: all of them are convinced (or so they claim) that innovation and technology will enable us to build an ecological civilization in which GDP growth will continue eternally and without damaging the environment.

Emmanuel Macron, who promotes a "French-style ecology" [2], is in fact defending a vision of ecology that is distressingly banal, since it is precisely the one shared by all the "elites" of the thermo-industrial civilization, with the idea of making an "ecological transition" through innovation and technology, by producing and consuming more. When and how exactly, no one can say, but innovation will bring new modes of production and consumption enabling this incredible decoupling.

For years, national and supranational policies have been launched with the aim of supporting the Great Decoupling. We have already mentioned "French-style ecology", which is "an ecology that creates economic value and is based on an industrial strategy" [2]. Let's also mention the French Energy Transition Law for Green Growth, which explicitly mentions the objective of achieving growth decoupled from carbon emissions [3]. And the European Green Deal, which aims for "a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy" to achieve "economic growth decoupled from resource use" [4].

Signs of decoupling?

As we've already mentioned, decoupling is not a new idea, and has been at the heart of major public policies for decades. So, are these efforts bearing fruit? In other words, is there any evidence to support this scenario?

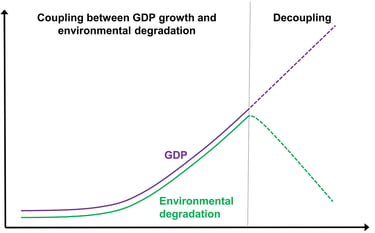

Well, let's not be in bad faith: yes, things are happening. For example, the carbon intensity of GDP (the amount of CO2 emitted to produce one unit of GDP) fell by more than 50% (53%) between 1980 and 2022 worldwide.

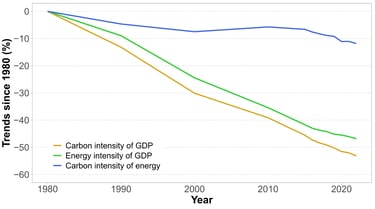

Figure 2: Relative change in carbon intensity of GDP, energy intensity of GDP and carbon intensity of energy between 1980 and 2022 at global level. Source: Our World In Data [5].

This means that for one point of GDP, we emit 53% less carbon today than we did 40 years ago. This is because, over the same period, both the energy intensity of GDP (the amount of energy needed to produce one unit of GDP) and the carbon intensity of energy (the amount of CO2 emitted to produce one unit of energy) have fallen: the energy intensity of GDP has dropped by 47%, while the carbon intensity of energy has fallen by 12% (Figure 1).

This reduction is due in particular to the use of less carbon-intensive technologies in energy production (renewable energies, nuclear power, etc.) and more efficient technologies in industrial processes.

So everything is fine, we are saved? Innovation and technology will allow the Great Decoupling? No?

A highly unlikely scenario

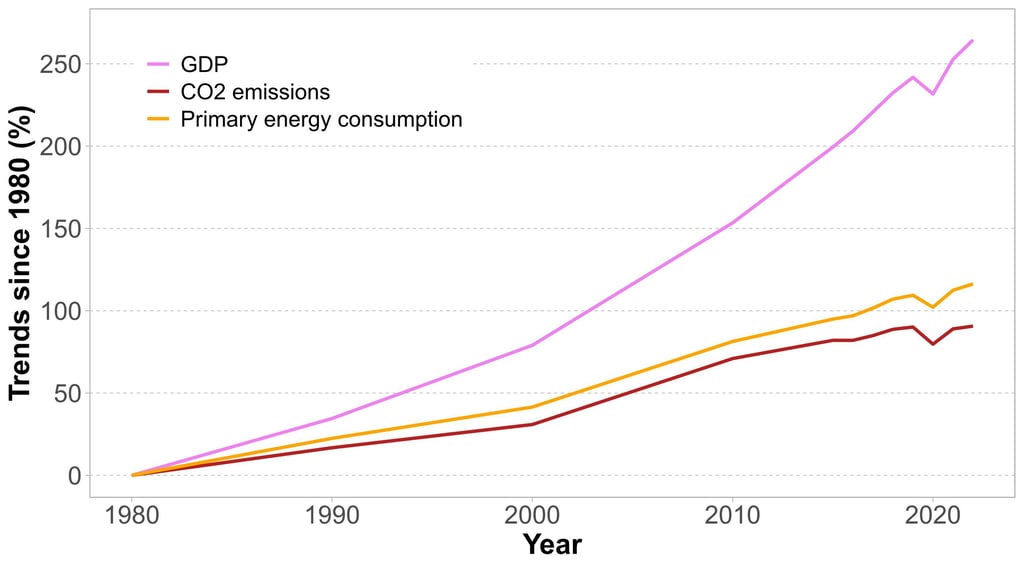

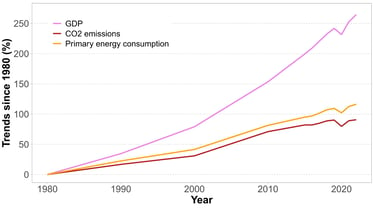

Unfortunately, the preceding paragraphs omit an important detail (that is not one): since the ultimate goal of human activity (well, of thermo-industrial civilization) is to increase GDP, the latter is continuing the meteoric rise it began decades ago. In fact, the increase in global GDP is such that the improvements described above remain largely insufficient to decouple economic growth from energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

In a nutshell: yes, GHG emissions and energy consumption are rising less quickly than GDP, but the fact remains that they continue to increase when GDP rises.

For example, between 1980 and 2022, global GDP increased by 265%, while primary energy consumption and CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry rose by 116% and 91% respectively.

The increase in energy consumption and CO2 emissions is smaller than that of GDP, but all these indicators remain closely linked.

Figure 3: Relative change in GDP, primary energy consumption and CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use and industry between 1980 and 2022 worldwide. While energy consumption and CO2 emissions are increasing less rapidly than GDP, due to the fall in the energy intensity and carbon intensity of GDP, they continue to rise sharply as GDP increases. Source: Our World In Data [6, 7, 8].

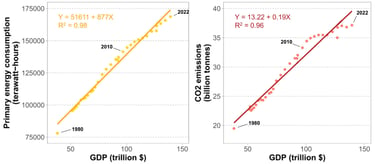

Figure 4: Relationships between GDP and energy consumption (left) and between GDP and CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry (right) at global level and for the period 1980-2022. Despite the decline in the energy intensity of GDP, the carbon intensity of energy and the carbon intensity of GDP, energy consumption and CO2 emissions remain very strongly linked to GDP. Source of data: Our World In Data [6, 7, 8].

What's more, and this is a major point that cannot be repeated often enough, the impact of human activity is far from limited to GHG emissions! The Great Acceleration curves reveal a total coupling between global economic growth and the alteration of the Earth's habitability, with GDP growth closely linked to increases in various indicators such as atmospheric GHG concentration, soil artificialisation, biosphere degradation, ocean acidification, loss of forest cover and species extinction rates [1]. On the Anthropocene dashboard drawn up by these curves, no transition is visible at this stage!

This observation is in line with the merciless conclusions of recent large-scale meta-analyses: the decoupling between GDP growth and environmental deterioration is not fast enough, is only partial (it only concerns certain aspects of environmental deterioration, such as GHG emissions), local (see on this subject the decoupling between demography and loss of forest cover in France) and relative (there is no absolute decoupling between GHG emissions and GDP growth, since both continue to increase) [9, 10].

The meta-analyses cited below thus conclude that the recent period does not demonstrate a decoupling commensurate with the stakes involved. Their other conclusion, just as crucial, is that it is highly unlikely that such a decoupling will occur in the short or medium term, for a number of reasons (rising energy costs, rebound effect, shifting problems, for example with electrification, which puts increasing pressure on certain resources, insufficient and inappropriate technological development, etc.).

The conclusion of all this is clear: the recent period shows no obvious signs of a major decoupling, and it is highly unlikely that this will occur in the short or medium term. As a result, and without even mentioning the major point of (non-)sense represented by the desire for infinite growth, we may well question the rationality of betting everything on the realization of such a hypothetical scenario.

References

[1] W. Steffen, W. Broadgate, L. Deutsch, O. Gaffney, et C. Ludwig, « The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration », Anthr. Rev., vol. 2, no 1, p. 81‑98, 2015. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2053019614564785

[2] E. Macron, « Déclaration de M. Emmanuel Macron, président de la République, sur la planification écologique, à Paris le 25 septembre 2023. », Vie publique. 2023. https://www.vie-publique.fr/discours/291196-emmanuel-macron-25092023-planification-ecologique

[3] Ministère de la Transition écologique et de la Cohésion des territoires, « Loi de transition énergétique pour la croissance verte », ecologie.gouv.fr. 2016. https://www.ecologie.gouv.fr/politiques-publiques/loi-transition-energetique-croissance-verte

[4] European Commission, « The European Green Deal », commission.europa.eu. 2019. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

[5] H. Ritchie, P. Rosado, et M. Roser, « Primary energy consumption per GDP ». Our World in Data. 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/energy-intensity

[6] H. Ritchie, P. Rosado, et M. Roser, « Energy Production and Consumption », Our World in Data. 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/energy-production-consumption

[7] M. Roser, P. Arriagada, J. Hasell, et E. Ortiz-Ospina, « Economic Growth », Our World in Data. 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/economic-growth

[8] H. Ritchie, P. Rosado, et M. Roser, « Greenhouse gas emissions », Our World in Data. 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/greenhouse-gas-emissions

[9] T. Parrique et al., « Decoupling debunked: Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. European Environmental Bureau. », 2019. https://eeb.org/library/decoupling-debunked/

[10] H. Haberl et al., « A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: synthesizing the insights », Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 15, no 6, p. 065003, 2020. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a

Conclusion

The Great Decoupling is the scenario on which thermo-industrial civilization has chosen to stake all its savings. Yet all the evidence suggests that this scenario is highly improbable!

If it's highly improbable, why choose this scenario? Quite simply because it's lazy, since it doesn't involve any serious questioning of our ways of thinking. In this respect, the Great Decoupling can be seen as the choice of immobility and constitutes a conservative scenario: the demiurgic ambition to control nature through science, innovation and technology, affirmed as early as the 17th century in the words of René Descartes or Francis Bacon, continues to be raised to the pinnacle, while GDP growth remains the compass of a disoriented thermo-industrial civilization.

Since the Great Decoupling is a scenario on which we're betting everything even though it's improbable, it's particularly risky. Without even talking about decoupling, the first risk is that the desire for infinite growth will lead to frustrations that generate tensions if growth can no longer be achieved due to elementary physical limitations. The second risk is that insufficient decoupling could lead to irreversible thresholds being exceeded in terms of environmental deterioration, which would push us into an unstable and dangerous zone. Could this lead to a Great Collapse of thermo-industrial civilization? A possibility I discuss in the next article.

Henri Cuny