Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

What future for the Anthropocene? - Scenario 2: The Great Collapse

Towards the fall of the thermo-industrial civilization?

Second part on the future of the Anthropocene, after a first part dedicated to the scenario on which thermo-industrial civilization is betting everything: that of the Great Decoupling. In contrast, we're now going to talk about a scenario that nobody (or almost nobody) wants, but which is nevertheless a plausible possibility for a growing number of us: that of the Great Collapse.

What is the Great Collapse ?

Collapse is one of those words likely to trigger epidermal reactions. It's true that since the collective imagination has been largely "Holywoodized", collapse is often perceived at first glance as a kind of Armageddon involving the total destruction of the planetary surface, or as a brutal event that would lead us into a new post-apocalyptic state "à la Mad Max".

However, some of those who have worked to popularize the concept reject this binary vision, presenting collapse as a more subtle process that needs to be understood in all its complexity [1]. It is therefore more appropriate to speak of collapses in the plural, as collapse can be multiple and depends on the facet we choose to observe. For example, from the point of view of biological indicators, the collapse of life on Earth has already begun and is scientifically documented [2, 3, 4, 5].

As far as the collapse of our civilization itself is concerned, the risk is more and more openly evoked. This is logical since, whatever we think of it, our civilization is based exclusively on a relatively stable climate, which is moving towards much greater instability, and on the massive exploitation of natural resources, some of which are becoming dangerously depleted.

But what is it, the collapse of our civilization? A return to the Middle Ages? The apocalypse? In contrast to the "end of the world" so often evoked since the dawn of time, the collapse of our civilization should perhaps rather be seen as the "end of a world", i.e. the one we know, based on mass industry and fossil fuels (as reflected in the term “thermo-industrial civilization”).

More than a single, punctual cataclysmic event, collapse can be envisaged as a long process (on the scale of human life) that "concerns not only natural events, but also (and above all) political, economic and social shocks, as well as events of a psychological nature (such as shifts in collective consciousness)" [1].

The collapse of the thermo-industrial civilization is therefore a generalized and potentially progressive failure of a system caused by a convergence of shocks at multiple levels: environmental, but also energetic, political, social, cultural, financial and economic. Collapse should therefore be seen as a transitional process towards something else: the Earth, along with life and humanity, will continue to exist.

The transitional process, however, should not be pleasant, as the very concrete definition given by Yves Cochet and Agnès Sinai suggests: collapse is "an irreversible process at the end of which basic needs (water, food, housing, clothing, energy, etc.) are no longer provided (at a reasonable cost) to a majority of the population by legally regulated services" [6].

It's easy to understand the risks inherent in such a collapse: the "barbarization" of society (a throwback to the "Mad Max" imaginary), tensions, wars, famines, etc., with a significant decrease in population and economic activity. The collapse would then translate into a major and unwanted drop in human development as measured by GDP.

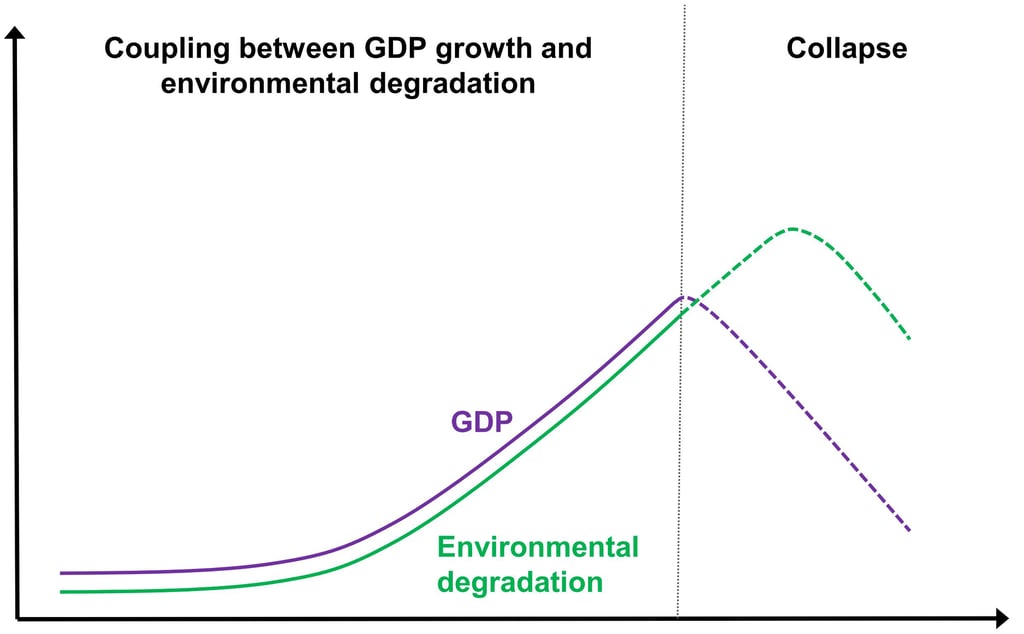

Figure 1: Illustration of the concept of the Great Collapse. The decoupling of growth, as measured by GDP, from environmental degradation, so much dreamed of by some, is not taking place, and instead there is a significant and undesired decline in GDP. The causes of this decline in economic activity are potentially multiple and concomitant, but may primarily involve environmental deterioration, declining resource availability and social inequalities. It is conceivable that environmental deterioration will initially continue or even worsen as a result of the breakdown of the thermo-industrial system, leading to maximum pressure on resources other than fossil fuels (wood, animals and plants of all kinds, etc.).

The causes of the Great Collapse are potentially numerous, but we can list three main ones: 1) environmental alteration beyond thresholds that cause the “Earth system” to enter a state of great instability, generating conditions that are far less favorable to economic development and, more generally, to life on Earth; 2) a reduction in the availability of resources; and 3) major social inequalities.

A scenario that is no longer taboo?

Collapse is a concept already present in earlier works. For example, the famous "The Limits to Growth" by Meadows et al. (also known as the "Meadows report" or "report to the Club of Rome") published as early as 1972 sets out the results of simulations carried out using a model of the “world system” (the World 3 model) which, in the event of continued economic growth, all lead to a collapse of civilization during the 21st century [7].

It is only in recent years, however, that collapse has come under the spotlight. An author like Jared Diamond contributed to this recognition with his 2005 book "Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed" [8]. Taking as his starting point the ephemeral nature of past civilizations, the author attempts to find common points in the disappearance of certain ones (the Mayas, the Vikings, the Anasazis...) in order to draw lessons and transpose them to contemporary times.

In France, the book "Comment tout peut s'effondrer : petit manuel de collapsologie à l'usage des générations présentes" (in english: "How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for our Times") written by Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens and published in 2015 had a certain impact and definitively established the collapse of our civilization as an important theory of our time [1].

So while collapse has long been seen as an apocalyptic tale of foolish catastrophists, it is now increasingly seen as a possibility that should not be ignored.

Some recent surveys attest to this change. An international survey carried out by the French International Market Research Group (IFOP) showed that belief in the possibility of a collapse of our civilization was shared by a good proportion, if not a majority, of the population in many coutries (71% in Italy, 65% in France, 56% in the UK, 52% in the USA and only 39% in Germany) [9]. A survey specific to France came to a similar conclusion, with around 60% of respondents fearing that collapse might occur [10].

Signs of collapse?

To assess the possibility of a Great Collapse of the thermo-industrial civilization, let's start with the three main causes listed above, and evaluate the current situation and recent trends for each.

Environmental degradation

In terms of environmental degradation, the trends summarized in the Anthropocene dashboard are crystal-clear, with a major acceleration in many indicators of Earth's surface alteration. Several planetary limits have already been exceeded, climate change over the last few decades has been staggering in its scale and brutality, and the continuing collapse of life could lead to the 6th extinction of life on Earth.

I often criticize the fact that climate change is given so much prominence compared to many other consequences of human activity (pollution with eternal pollutants, modification of biogeochemical cycles, collapse of life, etc.), but it's clear that the current trend and projections for the coming decades herald upheavals the scale of which we are probably struggling to grasp.

Resource availability

When it comes to resource availability, the Energy Return On Investment (EROI) is a very interesting indicator. To use energy, it must first be extracted from the environment. This extraction itself requires a certain expenditure of energy. Well, the EROI corresponds to the ratio between the energy produced from a given source (oil, wind power, nuclear power, etc.) to the amount of energy used to obtain that energy.

The greater the EROI, the greater the energy produced in relation to the energy invested in its production. A high EROI therefore corresponds to a favorable situation, and is a guarantee of continued high material prosperity [11].

As we have seen, our civilization is described as "thermo-industrial" because of its total and growing dependence on fossil fuels (oil, gas, coal) to feed an energy-intensive industry. Fossil fuels are indeed formidable concentrates of energy, yet their exploitation requires various energy-intensive operations (drilling, digging, pumping, etc.).

Logically, the most easily accessible resources are exploited first, which means that the EROI tends to fall as resources become more difficult to access, despite technological progress.

As specialist Louis Delannoy explains, "two examples illustrate this phenomenon: offshore drilling records continue to be broken (from 1,000 meters in 1994 to over 3,400 in 2020), and the oil liquids extracted are of poorer quality (heavy crude oil from Venezuela, tar sands from Canada, etc.). Whereas in 1950 the EROI was 50 for oil liquids production and 140 for gas, today their EROI are estimated at 9 and 25 respectively, and could decline rapidly to 2 and 16 by the middle of this century." [11]

Given that demand is growing at the same time, competition for fossil fuel supplies could become increasingly fierce, leading to dangerous levels of tension.

Although fossil fuels are the basic resources of our civilization, they are accompanied by many other indispensable resources. For example, the ongoing digital revolution and the drive to electrify many processes in the context of so-called energy transition (let's repeat: it's much more appropriate today to talk about accumulation than energy transition) imply an extraordinary growth in demand for a wide variety of metals. In fact, the quantities required are such that we run the risk of switching from one non-renewable resource (fossils) to another (metals) [12].

Generally speaking, in a context of economic growth, the increase in process efficiency is largely counterbalanced by other phenomena (notably the rebound effect, the displacement of problems as we have just seen with electrification, which shifts pressure onto new resources, etc.), so that the increase in population and consumption per capita translates into growing tensions over access to natural resources.

Inequality

Finally, with regard to social inequalities, the days of the lords seem to have returned once and for all, with an extraordinary monopolization of wealth by a minority of individuals after a few decades marked by a general trend towards reducing inequalities.

Inequalities are evident both globally and within a country's own population. For example, according to 2017 figures, the just over 2,000 billionaires in the world own more wealth than the world's 4.6 billion poorest people [13]. In other words, 0.000025% of the world's people own more wealth than 60% of the rest combined! Similarly, the wealth of the world's richest 1% is more than double the combined wealth of 92% of the world's population.

Even within the so-called "developed" countries, the indecent asymmetry in wealth sharing remains perfectly valid. In France, in 2017, seven billionaires owned more wealth than the poorest 30%, and the richest 10% concentrated half of the country's wealth. This monopolization of wealth by a handful of individuals, whom we can describe as super-predators, has been increasing in recent years, with the result that the gaps highlighted above are widening [14, 15].

In France, between 1996 and 2017, the 500 wealthiest individuals grew four times faster than GDP. These 500 alone accounted for 25% of GDP in 2017, compared with 6% in 1996. During these two decades, the number of billionaires rose from 11 to 92, while the total value of the 500 largest fortunes increased sevenfold, from €80 billion to €570 billion [16]. If nothing is done, the return on capital will remain much higher than the rate of growth of the economy in the years to come, so that these inequalities will mechanically continue to grow [15].

Of course, inequality is far from being confined to the economic sphere. For example, inequality of wealth generally means inequality of power. Indeed, the super-concentration of wealth goes hand in hand with a super-concentration of media and political power, as demonstrated by the stranglehold of a few ultra-rich individuals on France's leading media [17], or the growing collusion between economic and political "elites" in what some call "crony capitalism" [18].

Clearly, there are unbearable inequalities in our ability to contribute to collective decisions, and the few who monopolize the wealth are generally those who steer "the course of the world" in a system that claims the name "democracy" but tastes very much of plutocracy and oligarchy.

Finally, it's important to distinguish between inequality and poverty. Those who portray inequality often present the "non-rich" majority as a miserable mass of penniless people. However, economic growth has largely reduced poverty (although there are of course still people who are poor in the sense of struggling to meet their basic needs), as various indicators show.

However, inequality is a factor of tension independently of the question of the absolute level of wealth. Even if we were all "rich" (in the sense of being able to afford a profusion of goods and services), inequality would still be a source of tension. In the same vein, a profoundly unequal sharing of wealth between 4 people in a multi-billionaire family would surely generate dramatic tensions. So, clearly, even if economic growth has reduced poverty - an argument often used to say that growth must be pursued at all costs - the fact remains that the spectacular inequalities the process has generated are a decisive factor in the fragmentation of society, tension between individuals and, ultimately, unhappiness for many of us.

A likely scenario?

We have already mentioned the Meadows et al. report (1972), in which the authors detail the results of simulations carried out using the World 3 "world system" model [7]. Their main conclusion is that continued growth will sooner or later (during the 21st century, without necessarily giving a precise date) lead to collapse even if we are optimistic about technological development, recycling, pollution control or the availability of natural resources.

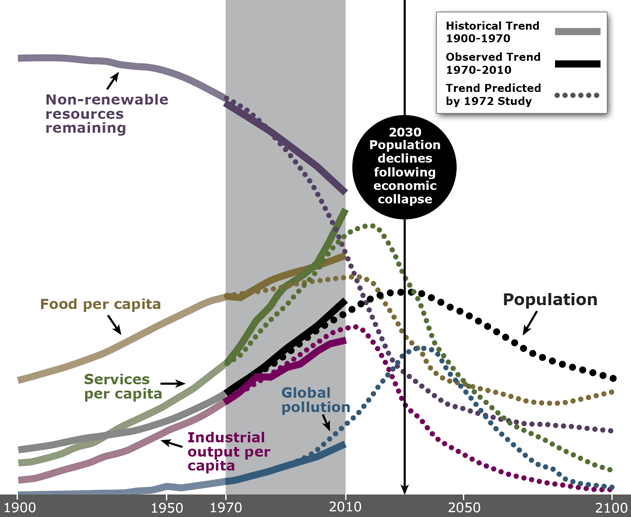

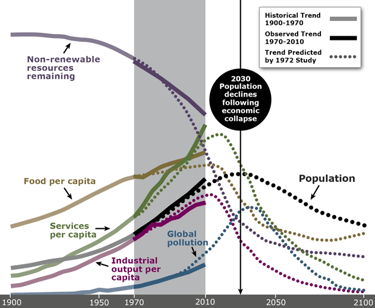

In 2012, a study compared the trajectories simulated by the Meadows et al. team for 6 indicators (available resources, food production, service production, population, pollution and industrial production) with actual data, and showed that the projections obtained with the most pessimistic scenario have so far proved to be fairly accurate, lending further credence to the thesis that humanity is on the brink of a perilous period [19].

Figure 2: Comparison of trends in 6 indicators simulated (World 3 model, "Business as usual" scenario) by the MIT team in 1972 with trends actually observed over the period 1970-2010. For all 6 indicators, actual trends are relatively close to those simulated.

A second, more recent study (2020) comparing empirical data and simulations confirmed that, without significant bifurcation, the trajectories followed could lead to a collapse of our civilization before 2040 [20, 21].

To grasp the threat of collapse, we need to say something about variation time. To do this, let's take up a metaphor used by Aurélien Barrau, and imagine a car hurtling along at 180 km/h [22]. In the first case, the car gradually brakes to a stop in a few seconds. In the second case, the car slams into a wall and stops in a few thousandths of a second.

In both cases, the amplitude of the change is the same: the car has gone from 180 km/h to 0 km/h. What differentiates the two cases is the variation time. This is an important parameter, since in the first case you stay alive, while in the second you're (most likely) dead.

Variation time is therefore essential for predicting the impact of a change on a system. However, what characterizes current changes (particularly the collapse of life and climate change) is their amplitude and exceptional speed, as shown by the great acceleration curves. Biological systems (including thermo-industrial civilization) are therefore going to have to adapt in an extremely short space of time, and this is probably what raises the threat to an existential level.

Even if the current situation is unprecedented in human history and the future is unpredictable, analysis of the past teaches us one thing: environmental degradation, climate change, social inequality and, even more so, the absence of any response to these problems, are recurring factors that have played a major role in the collapse of several civilizations [8].

When we talk about the risk of collapse, there's often someone who scornfully declares that it's gloomy pessimism to believe that our civilization could collapse; we'll find solutions when the time comes, and you only have to look back to understand that mankind has always been able to adapt. This belief is further reinforced by the narrative of the omnipotence conferred by modern technologies, with a linear progress that nothing can stop.

I think it's a major mistake to believe that just because mankind has survived the millennia by adapting to rapidly changing conditions, we'll be able to get through the challenges of the future without a hitch. An analysis of history is of little help, as current conditions, whether in terms of human organization systems or the global environment, are unprecedented. Humans survived trying ice ages as nomadic hunter-gatherers living in small autonomous groups, not as eight billion sedentary individuals ultra-dependent on a globalized system itself dependent on abundant, cheap energy.

In "How Everything Can Collapse", Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens explain that the dominant system, by phagocytizing all available resources (physical, economic, technical, psychological...), perpetually strengthens itself and thus increases its domination in a hellish loop that makes the emergence of any alternative impossible [1]. Eventually, the dominant system locks itself into place, making it extremely inertial.

At the same time, the system is becoming so sophisticated, with countless interdependent processes interwoven, that even a localized disturbance can, through contagion effects, spread to the whole and degenerate into a global crisis. Their conclusion is that the more powerful a system, the more complex and, paradoxically, fragile it becomes. The ultra-dominant, monstrously complex globalized system we have patiently built up over the last few centuries, in addition to being difficult to modify, could well be a giant with feet of clay.

References

[1] P. Servigne et R. Stevens, How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for our Times. Polity, 2020. (English edition of the book "Comment tout peut s'effondrer: Petit manuel de collapsologie à l'usage des générations présentes" published in 2015)

[2] G. Ceballos, P. R. Ehrlich, et P. H. Raven, « Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction », Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2020. https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1922686117

[3] G. Ceballos, P. R. Ehrlich, A. D. Barnosky, A. García, R. M. Pringle, et T. M. Palmer, « Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction », Sci. Adv., vol. 1, no 5, p. e1400253, 2015. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.1400253

[4] IPBES, « Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn, Germany », IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany, 2019. https://zenodo.org/record/3553579

[5] R. H. Cowie, P. Bouchet, et B. Fontaine, « The Sixth Mass Extinction: fact, fiction or speculation? », Biol. Rev., vol. 97, no 2, p. 640‑663, 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35014169/

[6] Wikipédia, « Collapsologie », Wikipédia. Consulté le: 14 septembre 2024. https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Collapsologie&oldid=217891631

[7] D. H. Meadows, D. L. Meadows, J. Randers, William W. Behrens III. The Limits to Growth. A Report for THE CLUB OF ROME'S Project on the Predicament of Mankink. Potomac Associates Books – Universe Books, 1972. https://collections.dartmouth.edu/xcdas-derivative/meadows/pdf/meadows_ltg-001.pdf?disposition=inline

[8] J. Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. Viking Press, 2005.

[9] IFOP, « Enquête internationale sur la « collapsologie » - Sondage Ifop pour la Fondation Jean Jaurès », Fondation Jean-Jaurès. https://www.jean-jaures.org/wp-content/uploads/drupal_fjj/redac/commun/productions/2020/1002/enquete_collapso.pdf

[10] G. Rozières et M. Balu, « 6 Français sur 10 redoutent un effondrement de notre civilisation », Le HuffPost. 2019. https://www.huffingtonpost.fr/c-est-demain/video/6-francais-sur-10-redoutent-un-effondrement-de-notre-civilisation-sondage-exclusif_156101.html

[11] L. Delannoy et E. Prados, « Les lois de la physique rendent la sobriété inévitable », Reporterre. 2022. https://reporterre.net/Les-lois-de-la-physique-rendent-la-sobriete-inevitable

[12] O. Vidal, B. Goffé, et N. Arndt, « Metals for a low-carbon society », Nat. Geosci., vol. 6, no 11, p. 894‑896, 2013. https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo1993

[13] D. A. V. Pimentel, I. M. Aymar, et M. Lawson, « Partager la richesse avec celles et ceux qui la créent », Oxfam, 2018. https://www.oxfam.org/fr/publications/partager-la-richesse-avec-celles-et-ceux-qui-la-creent

[14] F. Bourguignon et A. Châteauneuf-Malclès, « L’évolution des inégalités mondiales de 1870 à 2010 », SES.ENS-Lyon. 2016. http://ses.ens-lyon.fr/ressources/stats-a-la-une/levolution-des-inegalites-mondiales-de-1870-a-2010

[15] T. Piketty, Le capital au XXIe siècle. Seuil, 2013.

[16] A. Laratte, « La fortune des 500 Français les plus riches multipliée par sept en 20 ans », Le Parisien. 2017. https://www.leparisien.fr/economie/la-fortune-des-500-francais-les-plus-riches-multipliee-par-sept-en-20-ans-27-06-2017-7091565.php

[17] C. Sansu, S. Jacquier, M. Bonnéry, et C. Constant, « Qui sont les six milliardaires qui possèdent les principaux médias français », l’Humanité. 2023. https://www.humanite.fr/medias/bernard-arnault/qui-sont-les-six-milliardaires-qui-possedent-les-principaux-medias-francais

[18] J. Bouissou, « Une révolte contre le « capitalisme de connivence » », Le Monde. 2019. https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2019/11/08/une-revolte-contre-le-capitalisme-de-connivence_6018425_3210.html

[19] G. Turner, « Is global collapse imminent? An updated comparison of the Limits to Growth with historical data. MSSI Research Paper No. 4, Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, The University of Melbourne. », 2014. https://sustainable.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/2763500/MSSI-ResearchPaper-4_Turner_2014.pdf

[20] G. Herrington, « Update to limits to growth: Comparing the World3 model with empirical data », J. Ind. Ecol., vol. 25, no 3, p. 614‑626, 2021. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jiec.13084

[21] E. Helmore, « Yep, it’s bleak, says expert who tested 1970s end-of-the-world prediction », The Guardian, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jul/25/gaya-herrington-mit-study-the-limits-to-growth

[22] A. Barrau, « La fin du monde, l’autre option c’est vous. Conférence à la société des horlogers de Genève », YouTube. 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Meijmu60-AE

Conclusion

Once the preserve of a handful of doomsayers who were viewed with condescension by the general public, the "Great Collapse" scenario has gained ground and credibility in recent times.

It has to be said that recent trajectories and current conditions are conducive to this credibility: mix abrupt climate change, widespread collapse of the living world, depletion of natural resources, indecent social inequalities, all against a backdrop of a desire for unlimited growth (in population and the economy), and you get a potentially explosive cocktail.

Today, the Great Decoupling - the possibility of infinite growth while consuming fewer resources and without damaging the environment - is seen as the only possible way to avoid collapse. As we have seen, this is hardly credible. Does this mean there's no way out, and that the Great Collapse is inevitable?

Well, there is an alternative path, much simpler and in a sense more logical, but also infinitely less comfortable for our collective beliefs and the interests of some, and thus appearing to many as a repellent: the path of voluntary decrease in the economic activity as measured by GDP, what we call degrowth. So, after the collapse, the second "swear word" is dropped; I'll devote the next article to it.

Henri Cuny