Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

What future for the Anthropocene? - Scenario 3: Degrowth

Towards a transitional, equitable and voluntary reduction of the economy?

Third part on the future of the Anthropocene, after a first part on the current ferocious ambition of a very hypothetical Great Decoupling between GDP growth and Earth's surface alteration, followed by a second part on the possible Great Collapse of our thermo-industrial civilization. In this third part, we look at an alternative path that is a world away from the demiurgic project of decoupling, but which could nonetheless help avoid collapse: Degrowth.

Like collapse, degrowth is a word likely to trigger violent epidermal reactions (a "mot obus", in French). There have been countless attacks on degrowth from politicians of all stripes [1, 2, 3, 4], economists [5, 6, 7, 8], political commentators [9, 10], scientists [11], entrepreneurs [12, 13] and many others.

But what is this terrible degrowth, the mere mention of which arouses cold sweat and fevered hatred in some people?

What is degrowth ?

To define degrowth, let's say a word about the process to which it is opposed in every respect: growth; or, to be precise, growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This little indicator, which roughly measures the level of economic agitation*, has quite simply become the world's compass, and its growth has progressively imposed itself not as a transitory phase of incrasing economic production, but as an ultimate goal, a kind of modern-day quest for the Holy Grail.

Indeed, GDP growth is the goal of all current policies: without growth, its most zealous worshippers proclaim endlessly, our economy dies, our social system collapses, and ruin and despair await us all. Economic production and its corollary, consumption, must perpetually increase - there is no alternative.

Quite early on, some people criticized the vain, senseless, illusory and even dangerous nature of the project based on the quest for infinite growth. As early as 1934, Simon Kuznets, the very father of GDP, warned of the absurdity of making GDP growth an end in itself: “Those who demand more growth should clarify their thinking: more growth of what and for what?” [14]

However, it was during the 1960s and 1970s that the main concepts behind degrowth were formulated. While the aim here is not to provide a precise history of degrowth (for a history of degrowth, see for example "Ralentir ou Périr - Une économie de la décroissance" [in French] by Timothée Parrique [15]), let us nevertheless cite Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and his major work "The Entropy Law and the Economic Process" published in 1971.

In this book, the economy is conceptualized as a physical process of transformation of matter — natural resources are transformed to produce consumable goods and services — which is inevitably accompanied by an irreversible degradation and dissipation of matter and energy (the concept of entropy) [16]. Increasing the economy therefore means increasing irrecoverable losses, so that if we consider that our world is finite, infinite growth is impossible.

Let us also mention the world-famous "Meadows et al. report" or "report to the Club of Rome" published in 1972 and which also had a decisive influence on the emergence of the concept of degrowth [17]. This report presents the work of a team of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology led by Dennis and Donella Meadows. By carrying out simulations using a model of the "world system", the authors obtained the result that continuous growth in production-consumption inevitably ends in a systemic collapse.

The theory of Georgescu-Roegen and the findings of Meadows et al. have fueled the idea that infinite growth was impossible, but above all that a system based on the goal of growth could lead to dangerous ecological overshoots leading to its own crash. An obvious way to avoid this crash is to operate a "shrinkage of economic production" in order to take into account ecological limits, and it is indeed to this "shrinkage" that the term degrowth (then very little used at that time) refers.

It is finally only from the 2000s that the term degrowth really emerges to define, beyond the simple shrinkage of the economy, a new political project based on a system of values in opposition to that which underlies growth.

Growth is indeed no longer seen as a simple phenomenon of increase in production-consumption, but as an ideology or a sort of new universal religion, of which degrowth constitutes a radical critique. In this sense, Serge Latouche suggests that it is probably necessary to proceed with a "decolonization of the imaginary" of growth and that degrowth is above all an "a-growth", that is to say an atheism of growth [18, 19].

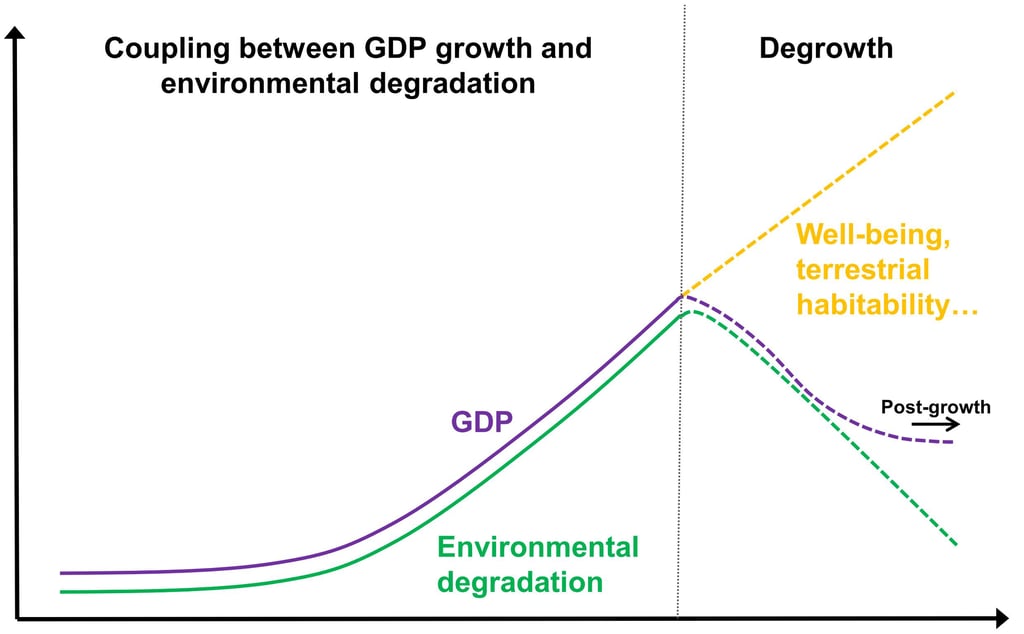

We discussed the project of a major decoupling between GDP growth and environmental deterioration in a previous article. Finally, the degrowth scenario is also a decoupling scenario, but this time the decoupling is between GDP growth and progress. Because abandoning GDP growth as a political project means abandoning the belief that GDP growth is the only guarantor of progress. To borrow a phrase used by Pierre Rabhi, decoupling growth from progress amounts to "freeing ourselves from the illusion that always more is always better" [20].

Figure 1: Illustration of the concept of degrowth. For decades, there has been a strong coupling between GDP growth and the alteration of Earth’s habitability, and an assimilation of GDP growth with the idea of progress. In a degrowth project, society organizes itself to voluntarily and equitably decrease economic activity as measured by GDP in order to take into account ecological limits; degrowth is not, however, an end in itself, but a transition to a steady-state economy (or "post-growth" economy), in which the idea of progress is dissociated from GDP growth.

Once we no longer believe in GDP growth as a path to salvation for humanity, degrowth can appear as a process that is not only necessary, but above all desirable. Degrowth then constitutes a new political project of transitional, equitable and voluntary reduction of GDP

These three words — "transitional", "equitable" and "voluntary" — are essential to understanding degrowth. The word "transitional" indicates that unlike GDP growth, which has become an end in itself to be pursued eternally, degrowth is a transitional way of reducing economic production. This reduction must lead to a new state, called the steady-state economy or post-growth economy, in which the economy is freed from the imperative of growth (i.e. growth is no longer a prerequisite for the vitality of the economy and the social system) and in which the level of production is compatible with ecological limits.

The word "equitable" indicates that degrowth must obviously be fair in relation to the wealth of each individual. Noting that poverty is today in many countries a problem of allocation rather than of the level of economic production (as evidenced by the staggering disparities in wealth between individuals), the idea is that a decrease in GDP will not necessarily result in more poverty, or even on the contrary will allow many to live better, as long as economic production is more fairly distributed. In places in the world where economic production is currently insufficient, there is obviously no question of implementing a reduction in the economy.

Finally, the word "voluntary" means that degrowth is something desired. The "fair" and "voluntary" nature of degrowth also shows to what extent it must be distinguished from economic recession, which on the contrary constitutes an inequitable and forced decrease in GDP.

Ultimately, the concept of degrowth combines the aim of reducing the size of the economy to take into account ecological limits and the ambition of revising the beliefs and values that constitute the foundation of our society, in order to build a new collective project in which the importance of the economic sphere in our existence would be reduced, the final objective being to improve the well-being of all.

A good definition is given by Timothée Parrique in his book "Ralentir ou Périr - Une économie de la décroissance" [in French] [15]:

Degrowth is "a reduction in production and consumption to lighten the ecological footprint, democratically planned in a spirit of social justice and concern for well-being."

This degrowth is not an end in itself, but a transitional path that leads us to post-growth, that is:

"A steady-state economy in harmony with nature where decisions are made together and wealth is shared fairly so that we can prosper without growth."

Signs of a craze for degrowth ?

We mentioned it: while the term "degrowth" is not very common in the 20th century, it has been used more and more often since the early 2000s. Moreover, the literature on degrowth is in full... growth (one would be tempted to say that even the degrowth movement does not escape the incredible wave of growth), with more and more books (see the referencing on Timothée Parrique's blog) and scientific articles (hundreds of articles listed) on the subject.

Alongside this abundant literature, there are countless diatribes and gratuitous attacks against the concept of degrowth (see the few examples given in the introduction to this article), to the point where it occupies a prominent place in the media.

Here is a first sign of enthusiasm for degrowth: in "intellectual circles", the term seems particularly popular and in any case fueled by heated debates, between fervent supporters (not very visible in the mainstream media however) and hateful objectors (very visible on the other hand). These circles are however in no way representative of society and it is therefore appropriate to broaden the scope of our analysis. For this, we have a few opinion polls on the subject of degrowth, and their results are surprising!

A survey conducted in 2019 (by Odoxa for the "Movement of the Enterprises of France" [Medef], not known for its appeal for degrowth) among 3,011 Europeans concluded that "the appeal for 'degrowth' is strong: 67% of French people say they are in favor of it (also 70% of the British, 62% of the Spanish and 53% of the Italians - only the Germans are opposed to it at 54%)" [21, 22].

Another survey conducted in 2019 (still by Odoxa, for AVIVA Assurances, BFM Business and Challenges, not really degrowth supporters again) among 996 French people reached a lower plebiscite, but still with 54% of respondents preferring degrowth to green growth to preserve the environment [23].

Perhaps more surprisingly, this survey highlighted a certain political consensus on the subject: "if EELV supporters (editor's note: EELV was the French environmentalist party of the time) are 63% to say they are in favor of degrowth, the supporters of other - old or young - 'productivist' parties are also a majority to be in favor of it. Thus, 57% of left-wing supporters, 55% of LaREM (editor's note: French President Emmanuel Macron's party of the time) and 59% of LR (editor's note: the Republican right party) agree with this idea."

Other surveys are however more nuanced. An IFOP survey from 2023 showed that "the majority of French people are not ready to abandon the idea of growth: 57% think that growth and sobriety are compatible"; but "28% believe that to achieve energy sobriety, economic growth must be slowed down." [24] (editor’s note: the wording is ambiguous; slowing down economic growth does not mean decreasing, but rather growing less quickly).

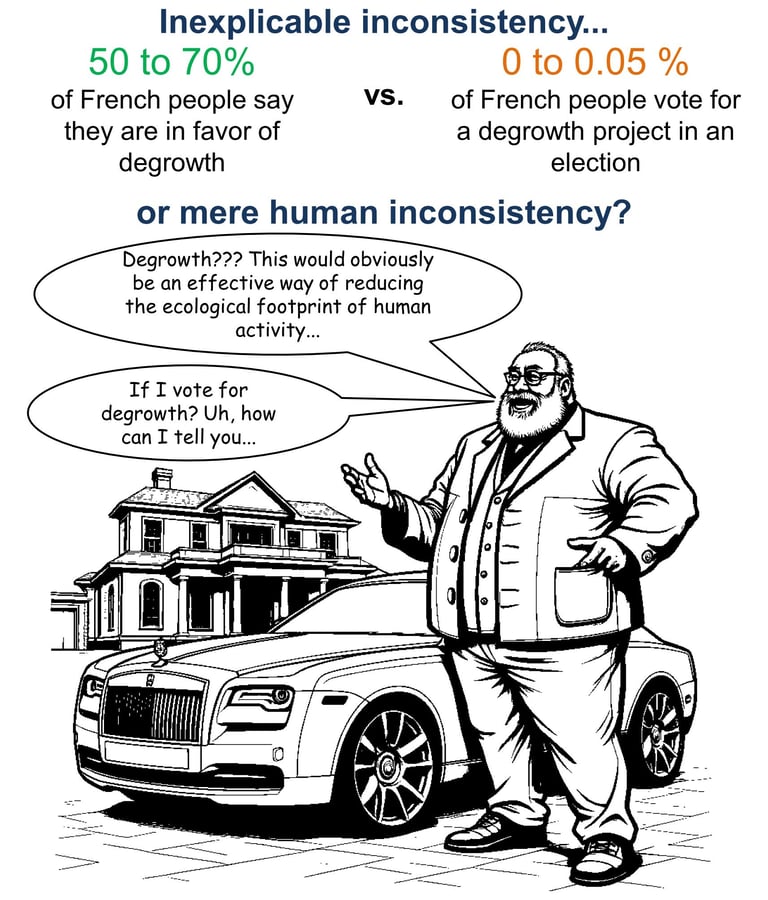

As we can see, the figures can change significantly depending on the polls and the way the questions are asked, but we can still reasonably think, given the orders of magnitude announced, that between a good quarter and a good half of French people are in favor of degrowth! Enough to constitute a solid basis for placing degrowth as a theme that counts in the public debate and as a serious candidate for a collective project for the future. No?

An impossible scenario?

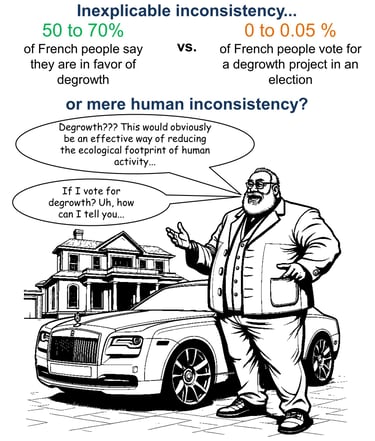

Alas, there are the opinions that people express when they are questioned for a given survey, and there are the opinions that they express when they are asked to take a position on a project, for example during an election. And the difference between the results of the aforementioned surveys and the results of political elections is truly abysmal!

To take a concrete example, let's take a look at the results of the most recent election in France: the 2024 legislative elections. In a district of the Vosges department (northeast France), there was only one list whose degrowth was explicitly on the program; all the other lists advocated GDP growth. This list scored 10 votes in the first round. Not 10% of the votes, but 10 votes out of the 48,623 voters, or 0.02% of the votes! [25]. In the few other constituencies where a "degrowth" list was presented, the results were of the same ilk [26].

In the 2024 European elections, the "Peace and Degrowth" list also peaked at a tiny 0.02% [27].

Obviously, answering a question in a poll is not the same as voting for a political project. It is almost certain that a poll on sharing would give a very large majority of respondents in favor of the need for a more equitable distribution of wealth, but it is nevertheless the political projects that authorize the current inequalities that are voted for. It is also almost certain that a poll could arrive at the conclusion that people make the preservation of life on Earth a priority, but the policies voted on are those that induce an alteration of the Earth's habitability and a collapse of life. Answering polls and voting are therefore two completely different things.

But, all the same, in the case of degrowth, the gap in results between opinion polls and elections is striking and clearly shows the gap that exists between seeing degrowth as a relevant means of building a more ecological society and actually wanting to engage in a degrowth project. In this case, it is not a gap, but an abyss!

Figure 2: There is a big difference between saying you are "in favour of degrowth", or thinking that degrowth would be an effective way of reducing the ecological footprint of human activity, and wanting to concretely engage in a real degrowth project.

It must also be said that everything is done to dissuade people from choosing degrowth. Politicians, economists and businessmen of all kinds take turns relentlessly in the media to profess the absolute necessity of growth and mock the "medieval" and deleterious project of the supporters of degrowth, portrayed as extremist ideologues (as if there were no ideology in the desire to pursue GDP growth at all costs) [9].

We can understand the determination of the major beneficiaries of GDP growth against degrowth, a project that effectively assumes that they lose certain privileges. More generally, we can understand the reluctance of the "believers", and there are many of them, who see GDP growth as the only way to progress.

Unlike the Great Decoupling scenario, the Degrowth scenario is a demanding and uncomfortable scenario, since it implies a total questioning of the ideology of growth (cultural revolution), which permeates us deeply, as well as a profound reorganization of society (social revolution). A bit like religious people whose faith would be seriously questioned, such a questioning is certainly uncomfortable for those who believe hard as iron in the growth of the GDP.

Within the French Green Party itself, a circle in which one could expect degrowth to receive a more favorable echo and to be at least at the heart of the debates (as we saw above, more than 60% of the members of the Green Party would be "adepts of degrowth"), the caciques, in the traditional pusillanimity inherent to this political party, carefully avoid positioning themselves on the subject by using different pirouettes [28].

During the 2021 Green primary to designate the candidate for the French presidential election, only one candidate (Delphine Batho) spoke openly about degrowth; she did not succeed in making the growth/degrowth opposition a major theme of debate and was eliminated in the first round with 22% of the vote [29].

In the scientific community too, and despite the enthusiasm mentioned above, the degrowth scenario ultimately remains rather ignored. To illustrate this, I am taking up here an analysis of the IPCC Group 3 report (2022) by Jean-Baptiste Fressoz [30]. This report is a large tome of 2,900 pages. The word "transition" appears about 2,700 times; the word "degrowth" only 26 times, most of the time in footnotes. Of the 3,131 scenarios submitted for the enormous simulation work presented in the report, none included economic degrowth.

To summarize: degrowth receives almost no votes during public consultations; and even the people who would be most likely to talk about it (political ecologists, scientists) most of the time refuse the simple use of the term. Suffice to say that we leave very little chance for the realization of this scenario!

A criticism often leveled at degrowth is that it remains, after all, very theoretical [31, 32]. Certainly, but how could it be otherwise in a society that shuns any calm debate on the subject (degrowth is discussed in the media, but generally in such a caricatured and fallacious way, with an ultra-preponderant place left to hateful detractors, that any serious debate is impossible) and in which no experimentation, even local, of the process is possible?

Notes

*More precisely, GDP measures the market value added of all goods and services sold during a given year, as well as the cost of production of non-market services provided by public administrations (education, health, etc.). To put it simply, GDP is the sum of all the money spent during a year. GDP growth therefore characterizes the increase in spending from one year to the next.

References

[1] Le Figaro, «La décroissance n’est pas une réponse au défi climatique», explique Emmanuel Macron, (2020). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tVH04X2gSAc

[2] L. Ferry, « Pourquoi la décroissance serait catastrophique », Le Figaro. 2021. https://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/societe/luc-ferry-pourquoi-la-decroissance-serait-catastrophique-20211215

[3] N. Monier, « Rentrée du Medef : « La décroissance, c’est remettre en cause notre modèle social », estime E. Borne », LSA. 2023. https://www.lsa-conso.fr/ref2023-elisabeth-borne-la-decroissance-c-est-remettre-en-cause-notre-modele-social,444511

[4] C. Mahoudeau, « Lors de l’université d’été du parti Reconquête!, Éric Zemmour propose de «dépolitiser» la France », Europe 1. 2024. https://www.europe1.fr/politique/lors-de-luniversite-dete-du-parti-reconquete-eric-zemmour-propose-de-depolitiser-la-france-4266174

[5] La Nouvelle République, « Esther Duflo : “Pour lutter contre la pauvreté, il faut se poser la question de la répartition des richesses” », lanouvellerepublique.fr. 2023. https://www.lanouvellerepublique.fr/a-la-une/esther-duflo-pour-lutter-contre-la-pauvrete-il-faut-se-poser-la-question-de-la-repartition-des-richesses

[6] C. Di Méo et J.-L. Harribey, « Les dangers du discours sur la décroissance », Politis, no 917, 2006. http://harribey.u-bordeaux.fr/travaux/soutenabilite/discours-decroissance.pdf

[7] É. Chaney, « Une critique de la raison décroissantiste », Telos. 2021. https://www.telos-eu.com/fr/economie/une-critique-de-la-raison-decroissantiste.html

[8] Thibault, « “Augmenter les impôts provoquera la décroissance” : la mise en garde de l’économiste Olivier Klein », L’Express. 2024. https://www.lexpress.fr/economie/augmenter-les-impots-provoquera-la-decroissance-la-mise-en-garde-de-leconomiste-olivier-klein-JH2Z4LZ7CRGC3MZD324WRXRMTM/

[9] N. Bouzou, « Misère de la décroissance », L’Express. 2020. https://www.lexpress.fr/economie/nicolas-bouzou-misere-de-la-decroissance_2125127.html

[10] V. Trémolet de Villers, « Dominique Reynié: «L’écologisme permet à la gauche de recycler son vieux combat contre le capitalisme» », Le Figaro. 2023. https://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/politique/dominique-reynie-l-ecologisme-permet-a-la-gauche-de-recycler-son-vieux-combat-contre-le-capitalisme-20231112

[11] R. Noyon, « « La décroissance est une lubie universitaire » : Matthew Huber, le marxiste qui défend le nucléaire et la lutte des classes », Le Nouvel Obs. 2024. https://www.nouvelobs.com/idees/20240823.OBS92717/la-decroissance-est-une-lubie-universitaire-matthew-huber-le-marxiste-qui-defend-le-nucleaire-et-la-lutte-des-classes.html

[12] BFM Business, « On ne sauvera pas la planète en faisant de la décroissance », selon Geoffroy Roux de Bézieux, (2023). https://www.bfmtv.com/economie/on-ne-sauvera-pas-la-planete-en-faisant-de-la-decroissance-selon-geoffroy-roux-de-bezieux_VN-202306160208.html

[13] L. Mediavilla, « Bertrand Piccard : “La décroissance ne tient pas compte de la réalité vécue par les citoyens” », L’Express. 2021. https://www.lexpress.fr/economie/bertrand-piccard-la-decroissance-ne-tient-pas-compte-de-la-realite-vecue-par-les-citoyens_2161105.html

[14] C. Mouzon, « Le PIB nous trompe énormément », Alternatives Economiques. 2020. https://www.alternatives-economiques.fr/pib-trompe-enormement/00094920

[15] T. Parrique, Ralentir ou périr - L’économie de la décroissance, Seuil. 2022.

[16] N. Georgescu-Roegen, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process, 2014e éd. Harvard University Press, 1971.

[17] D. H. Meadows, D. L. Meadows, et J. Randers, Les limites à la croissance (dans un monde fini) − Le rapport Meadows, 30 ans après. Rue de l’échiquier, 2012.

[18] S. Latouche, « Pour une société de décroissance », Le Monde diplomatique. 2003. https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2003/11/LATOUCHE/10651

[19] S. Latouche, « La décroissance ou le sens des limites », Le Monde diplomatique. 2016. https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/publications/manuel_d_economie_critique/a57054

[20] P. Rabhi, « Changer tout ... ». 2012. http://jdm.eklablog.fr/changer-tout-a102402325?noajax&mobile=1

[21] Odoxa, « Le progrès : Regard des Français & des Européens - Étude Odoxa pour la commission innovation du MEDEF ». 2020. http://www.odoxa.fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Odoxa-Commission-Innovation-Medef-Le-progres-3.pdf

[22] Odoxa-MEDEF, « Le rapport au progrès : Regard des Français et comparatif européen (sens, valeur, adhésion, partage et diffusion) ». 2020. https://www.medef.com/uploads/media/default/0019/96/13294-progres-synthese-actualisee-post-covid-sondage-medef.pdf

[23] Odoxa, « Les Français, plus « écolos » que jamais », Odoxa. 2019. https://www.odoxa.fr/sondage/barometre-economique-doctobre-francais-plus-ecolos-jamais/

[24] IFOP, « [INFOGRAPHIE] “Oui” à la sobriété mais “non” à la décroissance », IFOP. 2023. https://www.ifop.com/publication/infographie-oui-a-la-sobriete-mais-non-a-la-decroissance/

[25] Ministère de l’Intérieur, « Publication des candidatures et des résultats aux élections - Législatives 2024 ». 2024. https://www.archives-resultats-elections.interieur.gouv.fr/resultats/legislatives2024/ensemble_geographique/44/88/8802/index.php

[26] « Législatives 2024 : Résultats et Communiqués », Décroissance Elections. https://www.decroissance-elections.fr/legislatives-2024-resultats-et-communiques

[27] Rédaction Public Sénat, « Européennes 2024 : les résultats par liste et les projections en sièges », Public Sénat. https://www.publicsenat.fr/actualites/politique/europeennes-2024-suivez-tous-les-resultats-en-temps-reel

[28] J. Grandin de l’Eprevier, « Décroissance: le grand embarras des Verts », l’Opinion. 2021. https://www.lopinion.fr/economie/decroissance-le-grand-embarras-des-verts

[29] « Primaire présidentielle française de l’écologie de 2021 », Wikipédia. https://fr.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Primaire_pr%C3%A9sidentielle_fran%C3%A7aise_de_l%27%C3%A9cologie_de_2021&oldid=212651861

[30] Académie des sciences, Trajectoire de nos sociétés - Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, (2024). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PDftwPhO-zU

[31] J.-O. Engler, M.-F. Kretschmer, J. Rathgens, J. A. Ament, T. Huth, et H. von Wehrden, « 15 years of degrowth research: A systematic review », Ecol. Econ., vol. 218, p. 108101, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800923003646

[32] I. Savin et J. van den Bergh, « Reviewing studies of degrowth: Are claims matched by data, methods and policy analysis? », Ecol. Econ., vol. 226, p. 108324, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800924002210

Conclusion

Degrowth is ultimately a fairly old concept, enriched by decades of reflection, proposing a transitional, equitable and voluntary reduction in production-consumption to arrive at a post-growth economy, that is to say an economy freed from the imperative of growth and whose objective is the satisfaction of needs (that is, normally, the primary goal of an economy, before it becomes the continuous extension of needs and their monetization), taking into account planetary limits.

According to concordant surveys, degrowth is not seen by public opinion as a concept reserved for a few "extremists", but rather as a relevant path to achieve a "real ecological transition".

This rather positive vision of degrowth is not, however, reflected in public consultations: the scores of the very few candidates placing degrowth at the heart of their project are almost zero, and no stirring is felt in view of the results of the last elections.

At the same time, politicians, economists, business leaders and others take turns tirelessly in the media to affirm the absolute necessity of growth and castigate the unreasonable, even dangerous, nature of the "ideology of degrowth". In addition, all the forecasts, political as well as scientific, make growth the only conceivable scenario for the future.

In this context, the path of degrowth looks like a dark dead end: no space is left free even for a calm debate around this concept, not to mention possible practical implementations on an experimental basis.

Ultimately, the Degrowth scenario therefore seems very improbable. Enough to leave the field open to the Great Decoupling or the Great Collapse, the two other scenarios previously dissected? I give you my opinion on the future of the Anthropocene in a forthcoming summary.

Henri Cuny