Articles on the Anthropocene

In-depth articles on the Anthropocene

Palm oil: cause of ecological disaster, or consequence of economic growth?

Palm oil, or how to view ecological catastrophe through the wrong end of the telescope

Palm oil is identified as the cause of a major ecological disaster and is publicly called out (as seen here on a 2021 sticker from the Swiss Young Greens). Rightfully so? Source: By MHM55 — Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=106705352

Palm oil is said to be an abomination, a disgrace, evil incarnate. You’ve surely come across those heartbreaking images of wandering monkeys, their eyes hollow, driven from their habitat—the tropical forests—razed to make way for oil palms. The scandal broke out, and our valiant industrialists, champions of an ecology that is “non-punitive,” “practical” (copyright B. Pompili [1]), and “economically valuable” (copyright E. Macron [2]), rushed to respond by proudly offering products labeled “palm oil-free” or made with “certified sustainable” palm oil. Consumers are reassured: they can keep enjoying their spreads and other calorie-dense treats without harming those poor monkeys. End of story… or a well-oiled narrative designed to lull the masses?

Palm oil, gravedigger of Southeast Asia’s tropical forests

Palm oil comes from the oil palm, a plant native to tropical Africa that unsurprisingly thrives in tropical zones. In fact, the oil palm yields two types of oil with similar properties: palm oil, extracted from the fruit’s flesh, and palm kernel oil, extracted from the seed. Producing palm oil (or palm kernel oil, for that matter) means planting oil palms, a crop that doesn’t replace nothing. It often requires razing tropical forests beforehand. In Indonesia and Malaysia, which together account for nearly 85% of global production (60% for Indonesia alone) [3], this agricultural expansion is one of the main drivers of deforestation [4]. In Malaysia, for instance, nearly half of recent forest loss is directly linked to the spread of oil palm monocultures [5].

Southeast Asia’s tropical forests are teeming with life; they are “biodiversity reservoirs”, in technical jargon. Destroying these forests means destroying a vital substrate for life itself, along with countless species, including emblematic ones already critically endangered, such as the orangutan, the pygmy elephant, and the Sumatran rhinoceros [6].

These forests also store vast amounts of carbon, both in the plants (biomass) and in the soil [7]. Their destruction releases massive quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, worsening climate change. To this already bitter tally, add persistent human rights violations, including documented cases of child labor and worker exploitation [6], and nutritional qualities that are widely considered poor (high omega-6 to omega-3 ratio, high saturated fat content, low levels of vitamins and minerals except for vitamin E [8]), although scientific literature remains cautious on the matter [9, 10, 11].

Faced with this damning evidence, public opinion delivers a clear verdict: palm oil is inextricably linked to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and climate change. It is therefore seen as particularly harmful to the environment, unlike alternatives such as rapeseed, sunflower, olive, or soybean oil [12].

So then, why palm oil?

Despite its devastating impact on the biosphere, palm oil production has continued to grow over the decades, so much so that it is now the most widely consumed vegetable oil in the world. In just 60 years (1961–2022), its production has increased fiftyfold, reaching nearly 80 million tonnes in 2022 [3] (Figure 1). Add palm kernel oil to the mix, and we’re looking at 87 million tonnes derived from the oil palm in 2022, compared to just 2 million tonnes back in 1961.

Figure 1: Global production of palm oil and palm kernel oil since 1961. In just over half a century, palm oil production has increased fiftyfold, while palm kernel oil production has grown seventeenfold. Altogether, oil derived from the oil palm has increased more than fortyfold since 1961, reaching 87 million tonnes in 2022. Data source: Our World In Data [3] (https://ourworldindata.org/palm-oil).

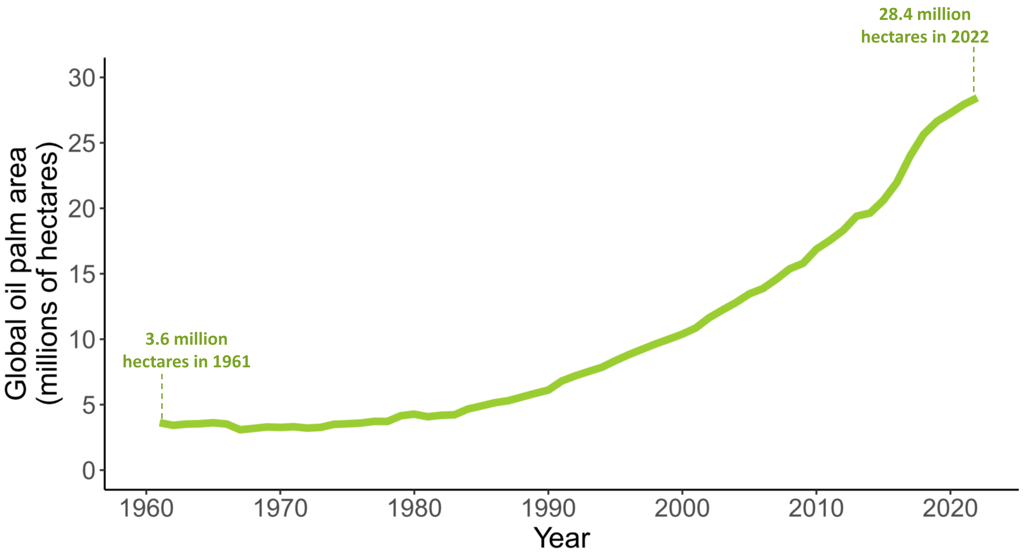

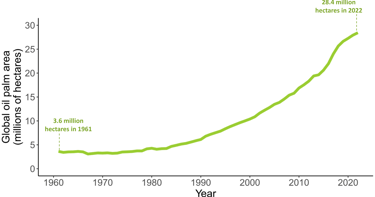

This explosive growth has, unsurprisingly, gone hand in hand with a surge in land use: today, just under 30 million hectares are devoted to palm oil cultivation, compared to just over 3 million in 1961 [3] (Figure 2). And the projections are alarming: an additional 36 million hectares will be needed by 2050 to meet expected demand [5].

Figure 2: Global expansion of oil palm cultivation since 1961. In just over half a century, the area dedicated to palm oil and palm kernel oil production has increased eightfold. Data source: Our World In Data [3] (https://ourworldindata.org/palm-oil).

Why such enthusiasm for palm oil despite its catastrophic impact on the biosphere? Because it combines decisive economic and technical advantages that make it a prized raw material—much like petroleum. Cheap, easy to produce, with high yields, semi-solid at room temperature, stable at high heat, odorless, colorless, palm oil’s real strength lies in its versatility, which explains its omnipresence in industrial production.

It’s found in a staggering array of products worldwide: around 68% of palm oil is used in food (margarine, chocolate, pizzas, cooking oils, animal feed), 27% in hygiene and cleaning products (soaps, detergents, cosmetics, cleaning agents), and 5% in energy (biofuels) [6].

Palm oil: a necessary evil?

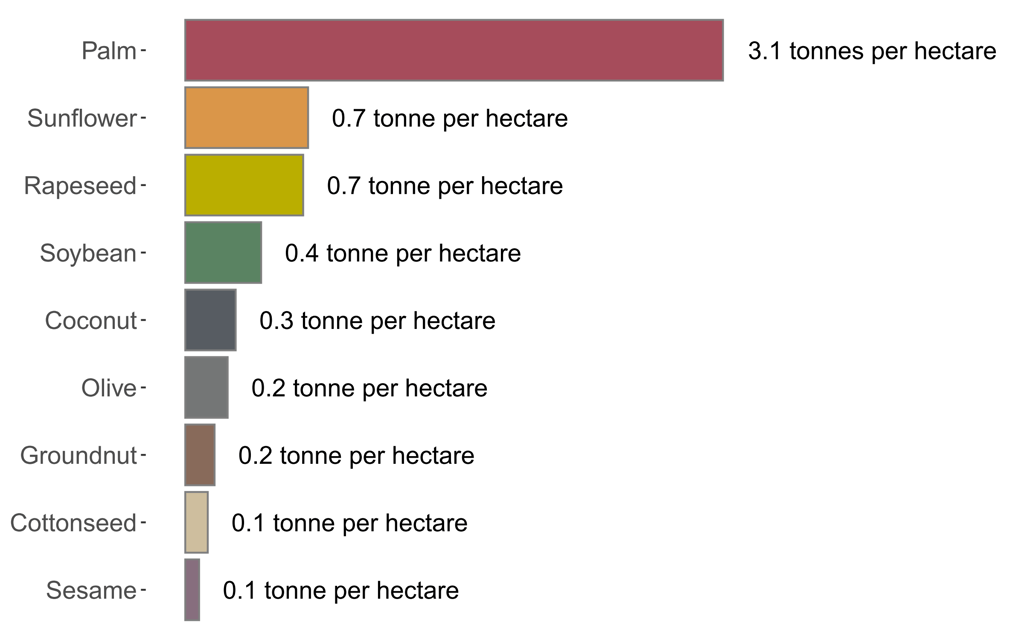

Let’s now focus on a key aspect of oil palm cultivation: yield. In terms of productivity, this crop is simply unbeatable. On equal land area, it produces far more oil than rapeseed, sunflower, or olive cultivation. One hectare of oil palms yields about 3 tonnes of oil, compared to just over 0.7 tonnes for sunflower or rapeseed, and less than 0.3 tonnes for olives [3] (Figure 3)! In other words, the yield of oil palm cultivation is 4 to 10 times higher than that of crops like sunflower, rapeseed, or olive. Put differently, to replace the oil derived from oil palms (palm oil and palm kernel oil), we’d need 4 times more land planted with sunflower or rapeseed, or 10 times more olive groves!

Figure 3: Comparison of oil yields from different crops. Oil palm has by far the highest yield. Data source: Our World In Data [3] (https://ourworldindata.org/palm-oil).

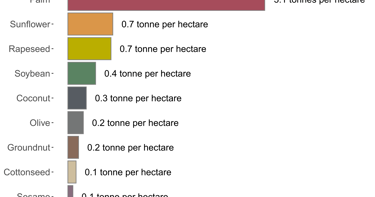

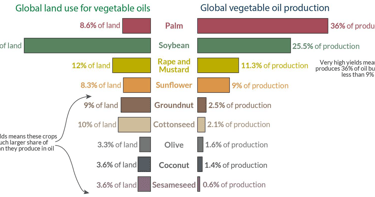

Figure 4: Share of different crops in cultivated land for vegetable oil production vs. share in total oil output. While occupying less than 9% of the land dedicated to vegetable oil production, palm oil accounts for 36% of total output. Data source: Our World In Data [3] (https://ourworldindata.org/palm-oil).

On a global scale, the imbalance between palm oil’s share of total vegetable oil production and the land it occupies highlights its decisive advantage: while palm oil accounts for nearly 36% of total vegetable oil volume (rising to 41% when palm kernel oil is included!), it uses less than 9% of the cultivated land dedicated to this production—about 29 million hectares out of the 300 million allocated to various forms of vegetable oil [3] (Figure 4).

Those who believe that replacing palm oil with lower-yield alternatives (sunflower, rapeseed, olive oil, etc.) is a good idea should think twice: Ultimately, it would mean significantly increasing the agricultural land required for vegetable oil production, and could therefore amplify the overall impact of this industry on the planet’s surface*. Viewed through the lens of yield and land use, palm oil appears less as an ecological calamity than as a pragmatic compromise.

Palm oil as a consequence of a catastrophic development model, rather than the cause of a disaster

From the previous section, we understand that replacing palm oil with lower-yield alternatives is not a viable solution, especially given the sheer volumes involved. The real question is not whether palm oil is “good” or “bad” for the planet, but rather why we need it, and in growing quantities.

The answer lies within the question itself: economic growth, which depends on the constant increase in the production and consumption of material goods and services, and is itself built on the perpetual extraction of natural resources, of which vegetable oil is just one among many.

In the case of vegetable oils, this extractivist logic is crystal clear. Production has increased twelvefold in just a few decades, from 17 million tonnes in 1961 to 211 million tonnes in 2022 (Figure 5). This explosion is driven by growing demand, itself fueled by population growth and rising individual consumption. For example, globally—and without accounting for vast spatial disparities—daily available caloric intake per person rose from around 2,200 kcal in 1961 to nearly 3,000 kcal in 2022 [13], while annual per capita vegetable oil consumption jumped from roughly 4.7 kg to 12.6 kg over the same period [14].

Figure 5: Global vegetable oil production since 1961. Palm oil (and palm kernel oil) production reflects a broader logic of resource accumulation to meet ever-growing demand: between 1961 and 2022, vegetable oil production increased twelvefold. Data source: Our World In Data [3] (https://ourworldindata.org/palm-oil).

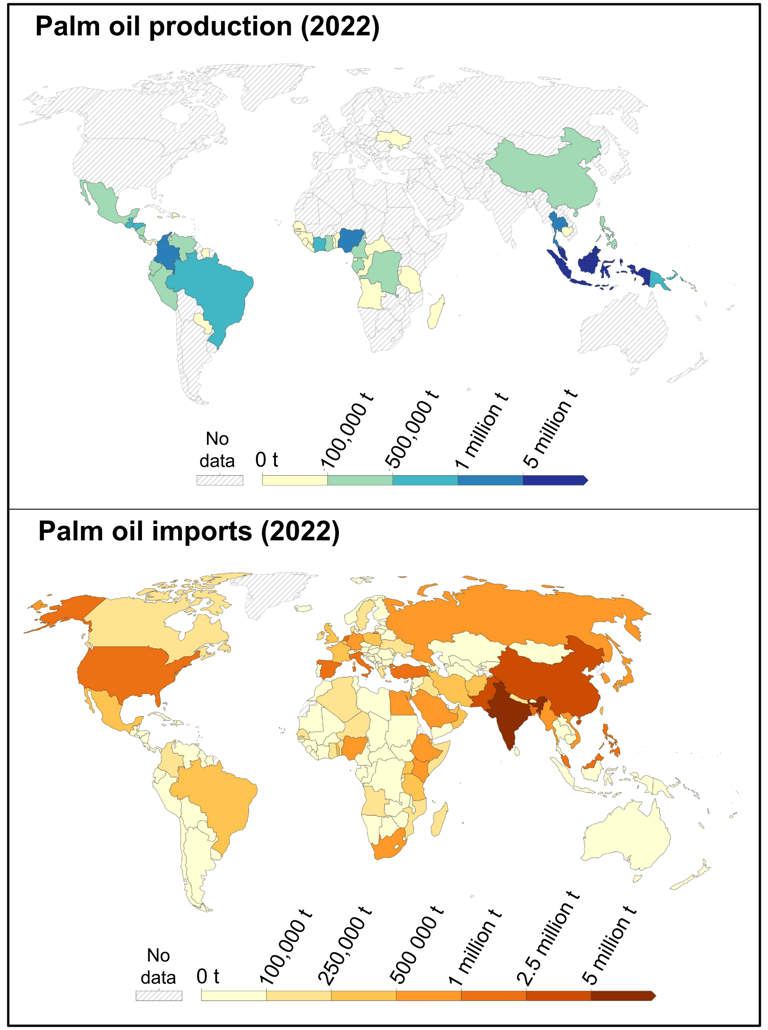

Figure 6: Maps of palm oil production and imports by country. Palm oil is produced in a handful of countries, then exported in a wide range of products across the globe. Map source: adapted from Our World In Data [3] (https://ourworldindata.org/palm-oil).

But how can we keep mobilizing ever more natural resources in a finite world? By relentlessly seeking to maximize productivity, efficiency, profitability, and performance in production systems. Oil palm cultivation perfectly illustrates this logic. It is just one of many intensive, hyper-productive systems designed to feed the raw material needs of societies that are greedy, insatiable, and obese—literally and figuratively—in the thermo-industrial civilization.

These intensive systems are fully embedded in the globalization process, as palm oil clearly shows: produced in select tropical regions, then exported to every corner of the globe (Figure 6).

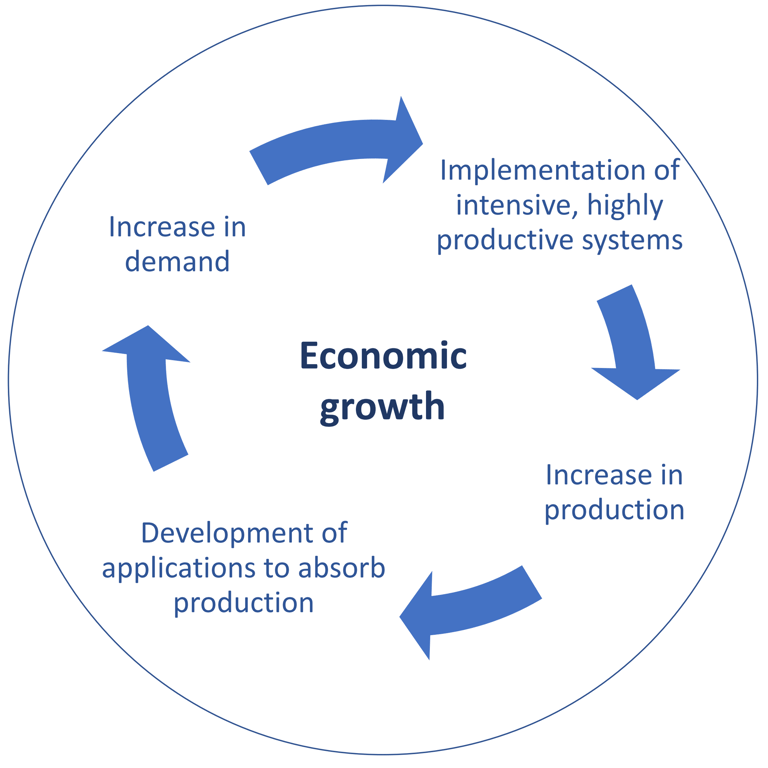

This model—combining hyper-production and globalization—fits more broadly into a vicious cycle that stems directly from the logic of economic growth (Figure 7).

Figure 7: The vicious cycle driven by the logic of economic growth. The “always more” mindset requires ever-increasing extraction of raw materials; the implementation of hyper-productive systems boosts the production of natural resources, which are then used in a multitude of applications of varying usefulness; in turn, resource demand rises and can only be met by deploying even more hyper-productive systems—and so the cycle continues.

The consequences of such a model are obvious: It traps us in a system of accumulation and makes us dependent on the productive structures in place, potentially located on the other side of the world. Two reasons explain this dependency: 1) The industrial chains involved are complex sectors that provide jobs and generate the sacred “value,” making them impervious to any ambition of dismantling; 2) The sheer quantities of resources at stake make any transition illusory unless it challenges the very foundations of the system, namely, economic growth and its accumulative dynamic.

The parallel with the energy transition is striking: thanks to their convenience and availability, fossil resources have led to an extraordinary surge in energy consumption, making oil, gas, and coal the backbone of our civilization, and rendering the idea of an energy transition without a radical shift in development models and a drastic reduction in energy use utterly unrealistic. In the same way, we’ve become addicted to palm oil, and we won’t be able to do without it unless we question the underlying model and drastically reduce the quantities of resources we consume.

This dependency manifests concretely in the food sector. To stimulate consumption, the industry multiplies attractive and addictive products. And the recipe is well known: plenty of fat and sugar. Nutella-style spreads, which combine these two ingredients in outrageous amounts, are a prime example of products designed for addiction. The sector behind them is powerful, job-generating, and economically valuable, so much so that no one would think to challenge its existence. Moreover, it requires astronomical quantities of oil (and sugar), which can only be supplied by intensive systems that thus become indispensable.

Trapped in this model, yet at least partially aware of its flaws, we then seek solutions, like producing “ethical” and “sustainable” spreads (because it would be a shame to give up this nutritional marvel) without ever questioning the broader framework (economic growth) in which this production takes place. An approach doomed to fail due to its incoherent attempt to spare both the goat (the spread industry, its consumers, its resource voracity) and the cabbage (ecological imperatives).

A more radical—but more coherent—approach would be to see palm oil as a consequence of a development model lethal to the biosphere, rather than as the cause of ecological disaster, which this article has sought to demonstrate. Palm oil is no longer the problem in itself; it’s our total oil consumption and its perpetual growth that constitute the deeper issue. From this perspective, it’s the spread itself that comes under fire, as a resource-intensive and nutritionally absurd product that’s hard to justify in a world concerned with ecological (and health) limits. The debate is no longer about which oil to use in the recip of spread, but about the scale, and even the legitimacy, of its production in a world of finite resources.

While palm oil is used here as an example, the reflection applies equally to other emblematic resources**, such as oil, which has become a cornerstone of our economic system and a source of deep dependency. More broadly, the issue lies not so much in the resource itself, but in the economic model that legitimizes its exploitation and makes its production seemingly indispensable. Therefore, pointing fingers at the widespread use of palm oil or oil (and its derivatives: gasoline, plastic, etc.) without questioning the logic of economic growth is of little relevance: it amounts to blaming the symptoms without addressing the root cause.

Notes

*Which makes the ads from manufacturers boasting about their “palm oil-free” spreads all the more ridiculous—complete with orangutan hugs and kisses [15].

**For the sake of consistency, it seems that critics of palm oil should broaden their critique to other crops—starting with coffee, whose cultivated area continues to grow globally (from 9 million hectares in 1961 to 11 million in 2021). Tea, cocoa, sugarcane, and more broadly all products inherited from the colonial era have also actively contributed to tropical deforestation, feeding the voracious appetites of so-called “developed” countries (i.e., the colonizers). Yet these products seem to enjoy critical immunity—their cultivation is long-established and thus perceived as normal and non-destructive to tropical forests (not to mention the strong consumer dependence on the products themselves). And what about all those cereal crops (wheat, corn, oats…) that have, in some cases for millennia, replaced temperate forests? Are these forests somehow worth less than tropical ones?

References

[1] France Info, « Loi Climat : Barbara Pompili défend une écologie de “bon sens” devant l’Assemblée nationale », franceinfo, 2021. https://www.franceinfo.fr/environnement/crise-climatique/convention-citoyenne-sur-le-climat/loi-climat-barbara-pompili-defend-une-ecologie-de-bon-sens-devant-l-assemblee-nationale_4352019.html

[2] E. Macron, « Déclaration de M. Emmanuel Macron, président de la République, sur la planification écologique, à Paris le 25 septembre 2023 », Vie publique, 2023. https://www.vie-publique.fr/discours/291196-emmanuel-macron-25092023-planification-ecologique

[3] H. Ritchie, « Palm Oil », Our World in Data, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/palm-oil

[4] V. Vijay, S. L. Pimm, C. N. Jenkins, et S. J. Smith, « The impacts of oil palm on recent deforestation and biodiversity loss », PloS one, vol. 11, no 7, p. e0159668, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159668

[5] E. Meijaard et al., « The environmental impacts of palm oil in context », Nature plants, vol. 6, no 12, p. 1418‑1426, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-020-00813-w

[6] WWF, « 8 things to know about palm oil | WWF », WWF. https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/8-things-know-about-palm-oil

[7] Y. Pan et al., « The enduring world forest carbon sink », Nature, vol. 631, no 8021, p. 563‑569, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07602-x.

[8] Alimentation & Nutrition, « Huile de palme raffinée valeurs nutritionnelles - Alimentation et Nutrition ». https://alimentation-et-nutrition.fr/huile-de-palme-raffinee-valeurs-nutritionnelles/

[9] J.-M. Lecerf, « L’huile de palme est-elle bonne ou mauvaise pour la santé ? », Pratiques en Nutrition: santé et alimentation, vol. 12, p. 20‑22, 2016. https://hal.science/hal-03487451/document

[10] K. Sundram, R. Sambanthamurthi, et Y.-A. Tan, « Palm fruit chemistry and nutrition », Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition, vol. 12, no 3, 2003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14506001/

[11] F. Marangoni et al., « Palm oil and human health. Meeting report of NFI: Nutrition Foundation of Italy symposium », International journal of food sciences and nutrition, vol. 68, no 6, p. 643‑655, 2017. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28142298/

[12] R. Ostfeld, D. Howarth, D. Reiner, et P. Krasny, « Peeling back the label—exploring sustainable palm oil ecolabelling and consumption in the United Kingdom », Environmental Research Letters, vol. 14, no 1, p. 014001, 2019. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aaf0e4

[13] H. Ritchie et M. Roser, « Obesity », Our World in Data, 2017. https://ourworldindata.org/obesity

[14] Our World in Data, « Vegetable oil supply per person vs. GDP per capita », Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/vegetable-oil-vs-gdp?time=earliest&country=~OWID_WRL

[15] F. Pouliquen, « Huile de palme - Procès perdu et mauvais coup de pub pour Nutella - Actualité - UFC-Que Choisir », UFC-Que Choisir, 2024. https://www.quechoisir.org/actualite-huile-de-palme-proces-perdu-et-mauvais-coup-de-pub-pour-nutella-n115874/

Conclusion

Palm oil production is only an anecdotal component of human activity, yet it serves as a powerful illustration of the danger of focusing on isolated processes (reductionist approach) without considering the interdependencies within the whole (holistic approach).

A reductionist “head-down” perspective easily leads one to believe that palm oil is the direct cause of a large-scale ecological disaster, and that its production must therefore be drastically curtailed in favor of supposedly more virtuous alternatives, all without necessarily questioning the underlying model that drives ever-increasing oil production and consumption.

By contrast, a holistic approach invites us to see palm oil as a consequence of a globalized model of (over)consumption, rather than as a direct cause of ecological collapse. Without a massive reduction in the quantities of vegetable oil consumed, replacing palm oil with lower-yield alternatives would mean expanding the land footprint of vegetable oil production, and could therefore worsen the catastrophe.

The deeper issue revealed here is that of economic growth, which presupposes the ever-increasing consumption of natural resources—including vegetable oil—and the implementation of hyper-productive systems without which the insatiable appetite of consumerist societies could not be satisfied. Only one viable solution emerges from this diagnosis: to reduce our consumption of natural resources and radically rethink our economic paradigm, which would require questioning the very existence of particularly resource-hungry productions (such as chocolate spread).

Henri Cuny