The Anthropocene Dictionary

Definitions of key notions and concepts related to the Anthropocene

Economy

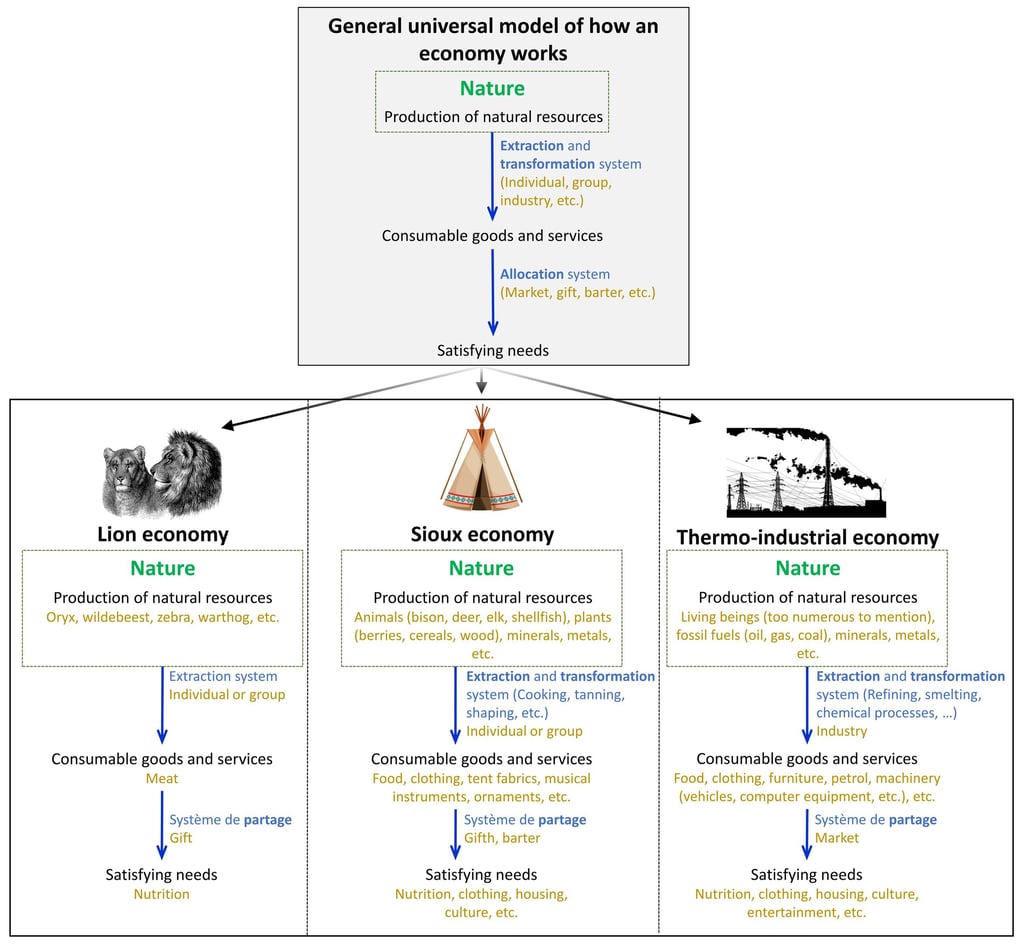

Definition: The economy refers to all the processes involved in satisfying human needs. It is the subject of the economics. In its physical dimension, the economy can be summarized by three key processes: the extraction of natural resources (wood, oil, sand, etc.), their transformation (sawing, refining, smelting, etc.) to produce consumable goods and services (furniture, gasoline, glass, etc.), and the allocation of these goods and services to different individuals. In its socio-organizational dimension, the economy can be described by systems of organization (capitalism, communism, etc.), systems of exchange (market, gift, barter), actors (individuals, households, companies, associations, etc.), sectors of activity (agriculture, industry, services, etc.), doctrines (economic liberalism, neo-liberalism, marxism, etc.), rules and principles (free trade, supply and demand, growth, competition, etc.), and so on.

The physical dimension of the economy fundamentally takes precedence over its socio-organizational dimension: an economy can perfectly well exist without well-defined rules, institutions or organizational systems; conversely, in the absence of natural resources and their production support (nature), the economy cannot exist. Despite this elementary truism, classical economics shows little regard for natural resources and nature, focusing instead exclusively on socio-organizational aspects, thus sidestepping what constitutes the very foundations of economics. Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's bioeconomics and ecological economics, however, place natural resources and nature at the heart of the economic game, and thus appear to be approaches capable of fostering a more integrative understanding of economics than classical economics.

In a broad definition, the economy can be seen as a fundamental aspect of the living world, with variations (in the resources used, modes of organization, etc.) depending on the species of living beings or human groups considered. For example, the economy of lions is based essentially on the harvesting and processing (ingestion and digestion) of various prey, such as antelopes. In contrast, the economy of thermo-industrial countries involves a huge diversity and quantity of resources (living organisms of all kinds, minerals, water, sand, etc.), but depends above all on the extraction and transformation of fossil resources (oil, gas and coal) by industry. Having made economic growth a fundamental principle, it also implies extracting and transforming ever more natural resources over time, which is a fundamental difference from the aforementioned lion economy, or more generally from the economy of many pre-industrial human populations or those who do not adhere to the economic growth model today.

The definition of the economy in pictures: The top box presents a universal model of how an economy works, seen as all the processes involved in satisfying needs from natural resources. The bottom three boxes present three variants of this universal model, with the Lion economy on the left, the Sioux economy in the center and the thermo-industrial economy on the right. These economies differ in terms of the resources used (in diversity and quantity), the extraction, transformation and allocation systems used, the goods and services generated, and so on. For example, the economy of the Lion is based on the harvesting of a variety of prey, essentially to meet food requirements. The Sioux economy is based on the harvesting and transformation of more diverse resources to produce a variety of goods and services to satisfy nutrition, clothing, housing and cultural needs... Finally, the thermo-industrial economy requires the extraction and transformation of a very wide range of natural resources (particularly fossil resources, which are at the heart of this economic model) to produce a large quantity and diversity of consumable goods and services. The thermo-industrial economy, by making economic growth a fundamental principle, differs radically from the other two models, as it requires the continuous extraction and transformation of more resources to produce more goods and services that can be consumed over time, thus supplying a multitude of "needs", some of which are anything but essential.